PARADE TO GLORY THE STORY OF THE SHRINERS

AND THEIR HOSPITALS FOR CRIPPLED CHILDREN

By Fred Van Deventer

NEW YORK, 1959 WILLIAM MORROW AND COMPANY

For Florence Copyright 1 1959 by Fred Van Deventer

All rights reserved.

Published simultaneously in the Dominion of Canada by George J. McLeod Limited, Toronto.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 59‑5505

Table of Contents Preface‑Es Selamu Aleikum in I Apostles of Good Cheer i II From All of These q III "Better Than They Knew" 21 IV The Legend of Araby 3 2 V In Death a Mystery 5 3 VI Hard Times‑and Growth 63 VII Fleming Says Farewell 71 VIII The Wells of Zemzem 83 IX The Power of the Throne 91 X End of an Era 112 XI Presidential Approval 120 XII With Charity for All i 2 q XIII The New Century 136 XIV To Faraway Places 152 XV "Our Lives, Our Fortunes" 164 XVI The Wells of Zemzem Run Dry 172 XVII The "Bubbles" Speech x‑78 XVIII Temples of Baby Smiles 191 XIX Unto the Least of These 204 XX Guests at the White House 209 XXI Dreams of Grandeur 217 XXII International Good Will 224 v XXIII The Great Depression 231 XXIV The Second World War 24‑7 XXV The Right to Go to Lodge 256 Appendix Rank of Temples According to Dates of Charters 277 Derivation and Significance of Temple Names 282 Cities with Temples 285 Past Imperial Potentates 288 Past Imperial Treasurers 292 Past Imperial Recorders 293 Shriners' Hospitals for Crippled Children, Directory 293 Index 29'7

Preface

Es Selamu A leikum

There is a story on how Parade to Glory came to be written.

Several years ago, when Florence Rinard (Mrs. Van Deventer) and I appeared on the television show "Twenty Questions," we took a short vacation in the southland. On our return, we were fortunate enough to meet on the Norfolk‑Cape Charles, Va., ferry, Mr. and Mrs. John Willey, who also had been vacationing. Mr. Willey is the editor of William Morrow & Co., the publishers of this book.

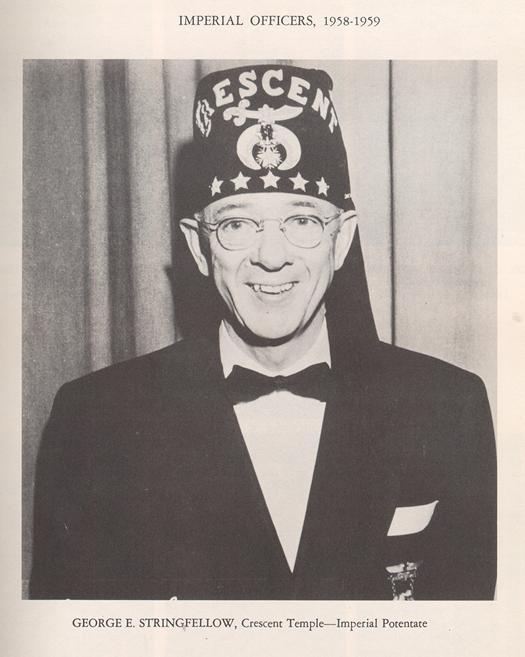

In the course of time, Mr. Willey and I had lunch together in New York, and at that luncheon I explained to him that ever since I had become a member of Crescent Temple, I had hoped someday to write the story of the Shriners and their hospitals. Mr. Willey expressed interest, and at his suggestion I approached Mr. George E. Stringfellow, who was then the Imperial Chief Rabban and also a member of Crescent. We had first come to know each other through my broadcasting of the news and also through the "Twenty Questions" program.

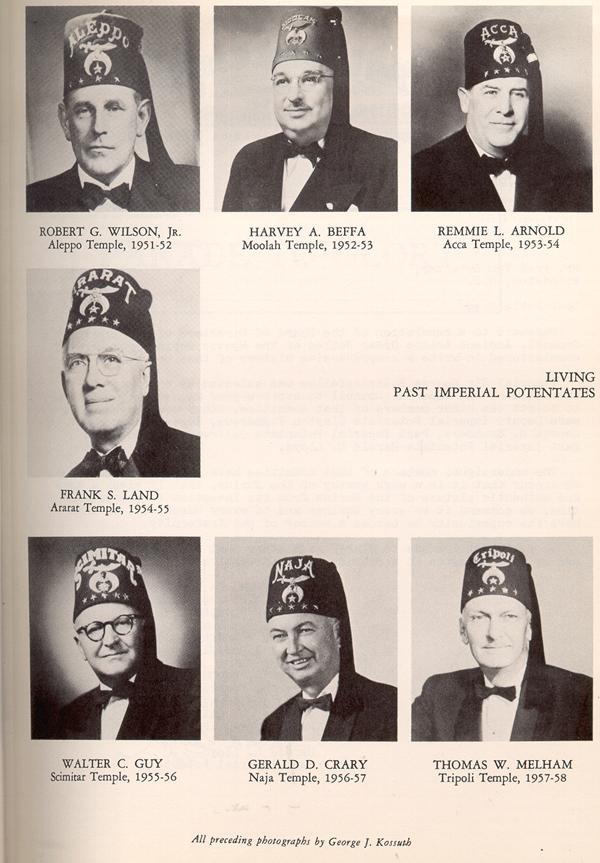

Imperial Sir George, without whose help, guidance and friendship this book could never have been written, presented the idea to the Imperial Divan, then headed by Imperial Sir Gerald Crary. More

vii Vila PREFACE

interest was expressed, further meetings were held, and the Imperial Divan approved the project in Minneapolis. Imperial Sir Thomas W. Melham, who had been elected in Minneapolis, signed the official documents that had been prepared by Legal Counsel Robert P. Smith.

There followed many thousands of miles of travel, seeking information wherever it might be found. I spent well over a year gathering information and photographs before ever one line was put to paper. They came from libraries from Maine to California and from Florida to the far northwest, from Recorders of all the temples, from emeritus members of the Imperial Council, from Past Imperial Potentates, from Arabic scholars, from the Shrine rooms in the George Washington National Masonic Memorial, from the late Noble Charles Bender of Mahi Temple, who had spent untold years and treasure collecting Shrine information.

There had been other histories of the Shrine written, the last one before the hospitals were really established, and there had been the legendary histories created by some of the early leaders of this great fraternal Order. But there never had been a story written about the glamour of the Shrine, the charity of the Shrine as well as the laws and the administration of the Shrine. This, then, is that story‑not a history in the exhaustive sense, for there are thousands upon thousands of anecdotes that could be told that are not included here.

For all who have helped, including my wife Florence and my daughter Nancy, I am indeed grateful. The book has made me a better Shriner and a better Mason. I hope it will you too.

FRED VAN DEVENTER

Princeton, N. J. January 1959

Selamu Es Aleikum

IMPERIAL POTENTATE 75 PROSPECT STREET EAST ORANGE, N.J.

Mr. Fred Van Deventer, Princeton, N.J.

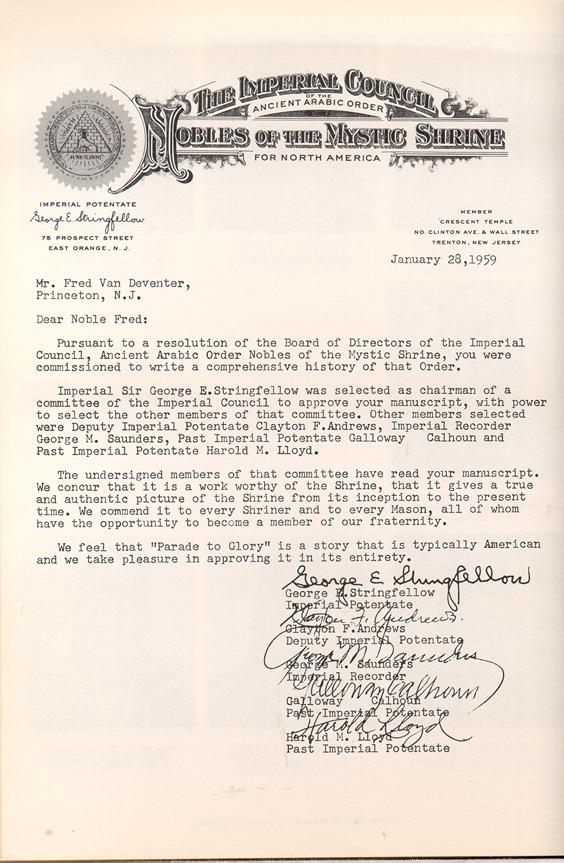

Pursuant to a resolution of the Board of Directors of the Imperial Council, Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, you were commissioned to write a comprehensive history of that Order.

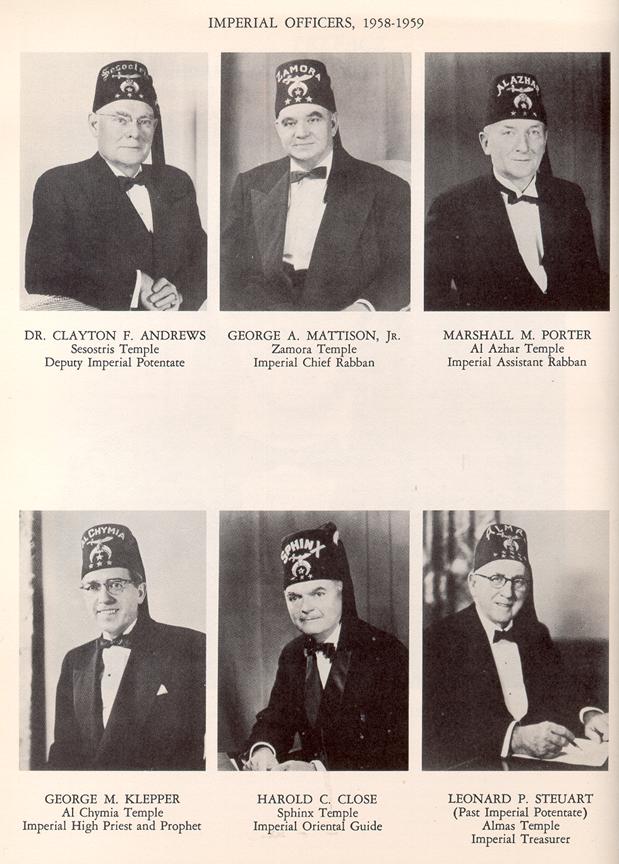

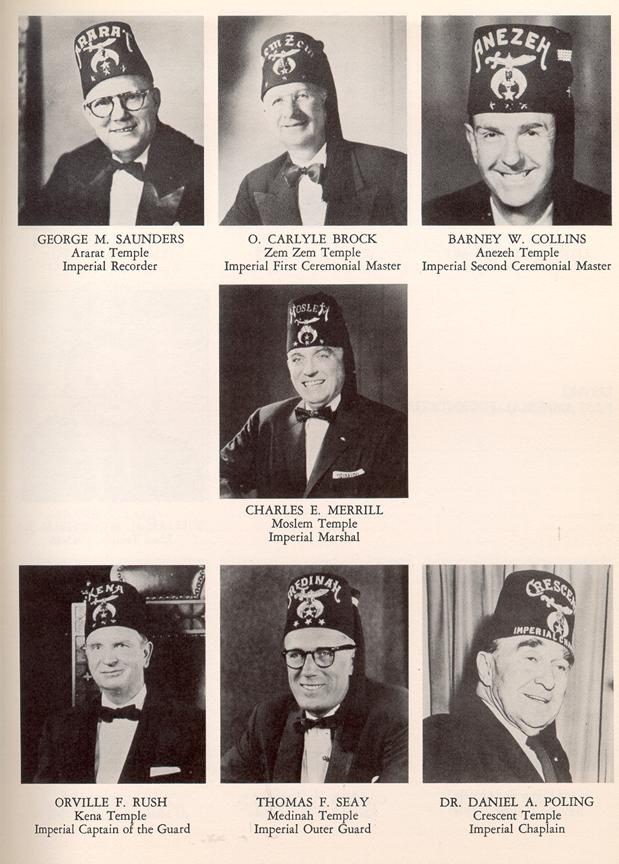

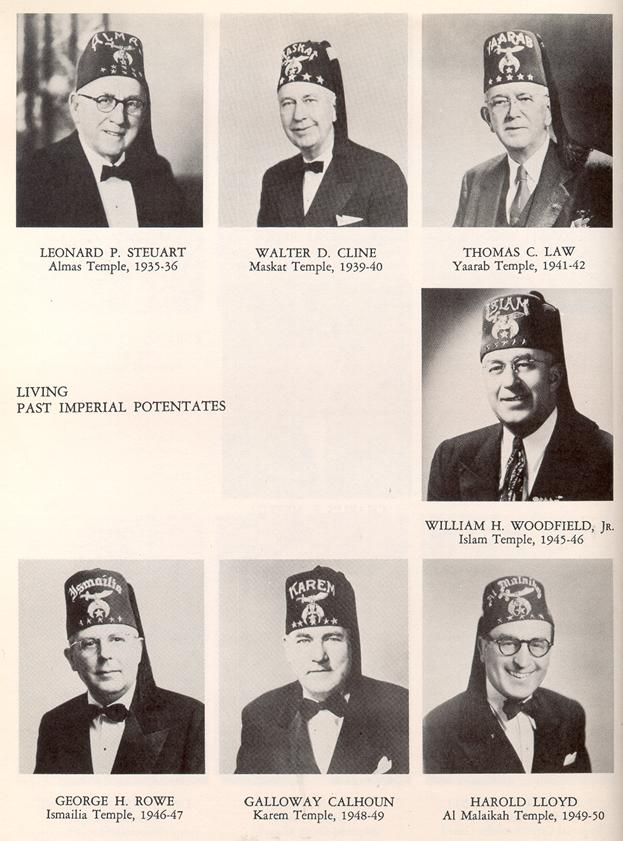

Imperial Sir George E. Stringfellow was selected as chairman of a committee of the Imperial Council to approve your manuscript, with power to select the other members of that committee. Other members selected were Deputy Imperial Potentate Clayton F. Andrews, Imperial Recorder George M. Saunders, Past Imperial Potentate Galloway Calhoun and Past Imperial Potentate Harold M. Lloyd.

The undersigned members of that committee have read your manuscript. We concur that it is a work worthy of the Shrine, that it gives a true and authentic picture of the Shrine from its inception to the present time. We commend it to every Shriner and to every Mason, all of whom have the opportunity to become a member of our fraternity.

We feel that "Parade to Glory" is a story that is typically American and we take pleasure in approving it in its entirety.

MEMBER CRESCENT TEMPLE NO. CLINTON AVE.& WALL STREET TRENTON, NEW JERSEY January 28,1959 George Inermate

PARADE T0 GLORY

Chapter I

Apostles of Good Cheer

IN THE spring and summer of 1870, the "13" craze swept New York City and among its more ardent devotees were Walter Millard Fleming, M.D.; William J. Florence, actor; Charles T. McClenachan, lawyer; William S. Paterson, paper merchant; George Millar, printer; and William Fowler, restaurateur and wine merchant. As much as anything else, the craze over "13" could be attributed to the aftermath of the War between the States, a flouting of all omens of ill‑luck in an effort to forget. There were those who insisted on sitting down to their luncheons at exactly 1z:13 at tables set for thirteen. Games were invented in which "13" played the dominant role, and attempts were made not infrequently to have thirteen persons at social affairs.

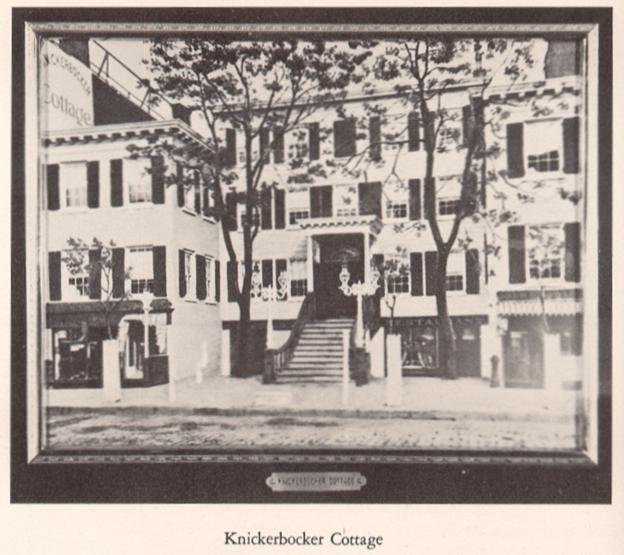

Among the luncheon tables set for thirteen guests was one on the second floor of Knickerbocker Cottage located at 426 Sixth Avenue, a popular bistro operated by Fowler and patronized largely by members of the Masonic fraternity, which was about to erect a new temple on nearby Twenty‑third Street. The fraternity had survived the political chicanery of the thirties that had produced an anti‑Mason political party, largely supported by Thurlow Weed in an effort to defeat Andrew Jackson, who was a Mason. But by the late thirties, the anti‑Masons had been maneuvered ‑by Weed and William H. Seward into the Whig party, where they promptly lost their identity.

APOSTLES OF GOOD CHEER 3

Now, thirty years later, Masonry was prosperous. There were many lodges of the first three degrees. The Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite was growing rapidly; and if the Knights Templar were a bit slower, it could be attributed to the cost of uniforms that every member must own.

There were thousands of Masons in the New York of 1870, many of them with businesses and offices that abounded in the vicinity of Twenty‑third Street. Banded together as they were in the spirit of fraternalism, it was quite natural and customary that they should carry that spirit outside their lodge rooms, and many of them made it a habit to visit Knickerbocker Cottage, which was housed in the old Varian Homestead, a large white house in the Dutch style, erected at Twentyeighth Street when that area was on the outskirts of the city. Its rooms were large and charming. The food was good and Knickerbocker Cottage had attained a certain notoriety because of both the size and the quality of its cellars.

There were several Masonic luncheon tables in Fowler's place, mostly made up of the same groups, day after day. Fowler promoted the idea of little cliques and was a member, or an honorary member, of most of them, for he was a popular host. But the most popular of all of the luncheon tables was the one on the second floor in a room that overlooked Sixth Avenue, a table set for thirteen. Faces at the large round table might vary from day to day, and there were occasions when its thirteen chairs were not filled, but no matter how many sat down at 12: 13, nor who attended on a given day, this table was one for fun. Perhaps the jokes were better. Perhaps there was more natural wit. Perhaps the select coterie was composed of the more natural extroverts who welcomed only those who could contribute to the merriment.

Dr. Fleming was an accepted member of that table for thirteen, and so were Florence, McClenachan, Paterson, Millar and others; and Fowler himself spent more time in the "13" room than elsewhere for here was the gayest of all gay company. For Dr. Fleming to be admitted to this select group was something of an achievement. It testi‑

4 PARADE TO GLORY

fied to his personal charm and his developing practice as a physician, for Dr. Fleming had hung out his shingle on Twenty‑eighth Street less than a year before.

Always, except in an emergency, Dr. Fleming made it a point to complete his morning rounds at nearby St. Elizabeth's Hospital and his morning calls at the homes of his patients before I 1: 45. Then, with his Homburg at a jaunty angle, he walked from his office to Fowler's in time to sit down with his cronies at exactly 12:13. He was just thirty‑two years old, but already he had begun to develop an expanding waistline, across which dangled a heavy gold chain, attached to an equally heavy gold watch. He sported long, flowing sideburns that dropped below his massive jowls; and even in a day when the cleanshaven man was a rarity, they attracted attention. His clothing was of the very best and, all in all, he radiated strength and character. He was exuberant and effervescent, but nevertheless he appeared to have a certain majesty about him. He was a large man, some five feet, nine inches tall and inclined to corpulence. The result was that he walked with a certain ponderousness, which belied his inner self.

Dr. Fleming was also a determined man. He had left a successful and lucrative practice in Rochester, New York, to become a part of this great city that was developing at the mouth of the Hudson and that even then‑five years after Appomattox‑was still celebrating the end of the bloodiest war in history. Parts of the Confederacy were still prostrate and sometimes starving, but in New York the only problem was to find new worlds to conquer. The French Empire was about to crumble before Bismarck and Victor Emmanuel would soon take over Rome and, in effect, restrict the temporal power of the Papacy to the Vatican grounds. But neither event would interrupt the flow of the finest wines and brandies to a city that was literally "living up" the preservation of the Union.

New York boasted of more than a million people, 900,000 of them on Manhattan Island, and was still growing. Factories sprang up almost overnight, and so did the splendid but architecturally grotesque mansions of the city's growing number of millionaires. The handsome, APOSTLES OF GOOD CHEER S silver‑mounted carriages of the new‑rich were drawn by matched pairs of whites, grays, bays and blacks over cobblestoned Broadway and Fifth Avenue, carrying ostrich‑plumed ladies to their milliners or to their favorite theaters, of which there were many. Show business was booming, and names still mentioned with awe in the history of the theater were just coming into full prominence.

Labor was scarce, but money was free and easy. When Fisk and Gould almost (but not quite) cornered the nation's gold supply in 1869 and thereby precipitated "Black Friday" on the New York Stock Exchange, the city staggered momentarily and then resumed its swagger. The golden spike had just been driven at Promontory, Utah, and now the millionaries could ride swiftly, if not comfortably, from New York to San Francisco. They wouldn't even worry about the Indians, for wasn't General George Custer, the dashing, flamboyant and perhaps inept hero of the Civil War, on guard? The scandals of Grant's administration were yet to come and if anyone at all gave the matter a thought, he could not have conceived of the panic of 1873. There was poverty, of course, and plenty of it, but even the poor had their beer, delivered by lumbering wagons and drunk as often as not under the gaslights of the neighborhood saloon.

It was indeed a time to be alive. The past was gone and best forgotten. The present was for living, and Fleming, Florence, McClenachan, Paterson and all the rest believed in living it to the fullest. But for Fleming there was also the future; and so it was that, sometime in the spring of 1870, there came to him while he sat at the table for thirteen at Fowler's an idea which developed through various vicissitudes (including use of the figure 13) into the Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine for North America.

No one knows the exact date when the idea came to the popular doctor. No one knows what germ of thought, what gem of wisdom, or what casual story by one of his comrades gave the doctor his in spiration. Still, the time is clear, and so are a few other essential facts, some of them contained in the Ritual of the Order, which now lies in glory and splendor in the Shrine rooms of the George Washing‑

6 PARADE TO GLORY

ton National Masonic Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia. Hand‑lettered in flowing design and illuminated with a now fading red ink, is the title page. It reads:

The First Complete. Ritual of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine Written for the establishment of the Order in the Western Hemisphere by Walter M. Fleming, M.D. of New York The Ritual undoubtedly is in Dr. Fleming's handwriting. It bears many corrections and, despite official changes, is in essence the same Ritual used in later years. The lodge room setting remains unchanged. There was succor then and now f or weary Sons of the Desert. The robes and other paraphernalia follow the chart today as they were laid down by the versatile doctor, and even the ceremony and most of the words are little removed from the original.

APOSTLES OF GOOD CHEER In 1950, when the Shrine rooms in the George Washington National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia, were created, Mecca Temple of New York City (the first in America) generously contributed the original Ritual along with other memorabilia belonging to Dr. Fleming and William J. Florence, one of America's truly great actors and comedians, who was credited by Dr. Fleming and others with being a co‑founder of the Shrine. On the inside cover of the Ritual, there is a notation, handwritten and signed by Dr. Saram R. Ellison, the second Recorder of Mecca Temple, which says: "In the latter part of 1901, Noble George W. Millar and I visited Dr. Walter M. Fleming, at the Imperial Hotel, his wife being sick at the time. He presented us with this Ritual, having found it in an unused trunk. He said it was the first complete Ritual of the Order. I had it mounted and bound, and it has been in our safe ever since." These and no more are the incontrovertible facts of the origin and founding of the Shrine. The remainder is partly fact, partly legend, partly fancy, partly fiction. But out of the welter of fact, fancy, legend and fiction has sprung the most colorful of all fraternal organizations. The Shriners have played and marched their way into a glory of fraternalism hitherto unknown in the world. And yet, considering its weird beginnings, its playfulness, its arguments (even with basic Masonry) it is perhaps amazing that the Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine continued to exist at all.

Many leaders of the Shrine, in the years since Dr. Fleming wrote his Ritual, have tried to describe just what the organization is. One of the best of these descriptions came from the pen of the late Dr. Hubert M. Poteat, a professor at Wake Forest College and a Past Imperial Potentate. He wrote: The Shrine appeals to the strong manhood of North America for a variety of reasons. In the first place, the oriental pageantry and the magnificence of costumes and regalia appeal to men who may be old in years but who are still young in spirit. Little boys play cops and robbers; Shriners play Moslems and infidels.

In the second place, the Shrine provides opportunity for fun and 7 8 PARADE TO GLORY play and mirth on a truly magnificent scale. Shriners are apostles of good cheer and happiness and as such are performing a very vital function in this tragic modern world of ours. Indeed it may be said that we have been "called into the Kingdom for such a time as this." A further important principle of the Shrine is toleration in the field of religious opinion. One of the most tragic phenomena of our times is the endless warfare among the people of different faiths and beliefs. In other words we expend most of our energies fighting one another instead of the devil. The Shrine will have none of it and instructs its initiates that they are to recognize the right of every human being to worship God as he sees fit, without interference or even criticism from any man who walks this planet.

If there is one thing our harassed world needs more than another today, it is brotherly love. This can be found nowhere in a finer or truer form than in the Mystic Shrine. This does not mean for a moment that all 'Shriners are the perfect embodiment of this quality. However, Shriners in general do live by this principle.

Such is the weak and fallible nature of man that he needs all the spiritual strengthening he can get; and the Shrine teaches its initiates as all Masonic bodies do, that God IS and that it is our duty to worship and to obey Him, to esteem Him as the chief good and to fight with all our power against atheism.

The story of the Shrine, then, is the story of men with reverent minds and merry hearts, men from every walk of life‑presidents, prime ministers, actors, judges, musicians, generals, admirals, mechan ics, doctors, lawyers, merchants, chiefs and no doubt a thief or two. And it is a story worth the telling.

Chaipfer2 From All of These S HRINERS play Moslems and infidels with reverent minds and merry hearts. Indeed! But Shriners are more than little boys grown tall. With all their fun, they have not forgotten charity. With all the splendor of their parades, they do not and cannot forget that first of all they are Master Masons with all of the humility they are taught by the craft. For most of the more than eight hundred thousand Shriners in North America, it is a matter of considerable pride that they wear the scimitar and crescent in their buttonholes as they go about their daily lives. It is with equal pride that they don the red fez with black tassel for more formal ceremonial occasions. But all of the fun, splendor and charity had to have a beginning, and this beginning must have come at some meeting in either 1869 or 187o between Dr. Fleming and Billy Florence.

There is no record of that first meeting, but it is more than likely that it came about when the handsome, gay, devil‑may‑care actor called on Dr. Fleming for treatment of some minor ailment, which in itself was something of a plume in the hat of a doctor new to New York. Billy Florence in 1869 was established as the toast of the theatrical world. It might be said that he was the George M. Cohan or Jack Benny of his day. He lived in the better hotels that lined Fifth Avenue, 9 10 PARADE TO GLORY and Dr. Fleming's house was just around the corner from the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Both were Master Masons and while Florence did not work at the craft with the same zeal as Dr. Fleming, he had, at that time, attained higher degrees. Once the business of medicine was out of the way, there was probably an inquiry about basic lodge, and after that an invitation to lunch and perhaps a bottle of wine. Thus are friendships born, and in truth Fleming and Florence were kindred souls, each with an insatiable zest for life and a gorgeous thirst. There was perhaps also some sort of adoration on the part of the young doctor for the handsome and popular star, for in reality Walter Fleming was a frustrated actor, whose life had been channeled by a doting father into the world of healing.

There were others too, in 1870, who undoubtedly contributed in some measure to the beginning of the Shrine, but just who contributed what is still subject to considerable controversy. Fifty years after the founding of the Shrine, James McGee, who became the twenty‑eighth member of Mecca Temple, and was the last survivor of an original thirty, wrote from memory his history of the organization, but it was labeled by Louis N. Donnatin, a Recorder of Mecca Temple, as "the ravings of a diseased mind." McGee carried his argument to the floor of the Imperial Council in 192o and in the light of subsequent revelations, it is more than likely that his story is nearer the truth than any other. All versions of the early and formative years of the Shrine are agreed, however, that four men carried the burden, with an assist from a fifth. These men were Fleming, Florence, McClenachan, Paterson and Fowler. Their backgrounds in life and in Masonry are important in the light of their contributions.

Walter M. Fleming was born in Portland, Maine, June 13, 1838, the younger of two sons of Dr. L. D. Fleming, who soon moved to Rochester, New York, and established a lucrative practice in a house on St. Paul Street in the heart of the thriving town. Both boys attended nearby Canandaigua Academy, and both boys matriculated at Albany Medical College.

FROM ALL OF THESE 11 The exact date when Walter entered Albany College is not known, for all of the early records of that institution have been destroyed by fire, but it must have been during the years when Webster and Clay were trying to save the Union and avoid the inevitable conflict between the North and the South. The best guess is that he enrolled in 1857, for the record shows that, without even having been graduated, he was named surgeon of the First Cavalry of the New York National Guard in 1858. In 1861, he served as surgeon to the Nineteenth Regiment of the same organization with the rank of lieutenant or ensign.

The records of the Adjutant General's office show that Fleming was "discharged in N.E.Va. dated August 3, 186 1 on tender of resignation in consequence of physical disability." The nature of the dis ability was not explained and Fleming himself never mentioned it, though in 1907 he applied for a pension. Undoubtedly his injuries were incident to the first movement of Northern forces into Virginia, which began on May 24 and continued until after the Union disaster at Bull Run in late July.

After his discharge, Fleming returned to the Albany Medical College and received his degree in 1862. Dr. Fleming then hung out his shingle in the same house with his father on St. Paul Street in Rochester, and it is apparent that in the ensuing years he developed quite a following and an extensive circle of convivial friends. In 1867 he was chosen by the city council in a competitive election with other doctors as one of two city physicians.

In that same year, his father died and Dr. Walter assumed the entire practice, but life in Rochester grew boring. Mrs. Mellan Lucas of Del Ray Beach, Florida, Dr. Fleming's granddaughter, recalls that in his later years he was an inveterate reader, so perhaps out of the daily press or the periodicals of the time, there came to him the desire to travel and participate in some of the glamour of which he read. In any event, the Rochester Union and Advertiser on April 3, 1869, revealed that the doctor had sold his practice in order to‑ remove to New York City. Two days later the same newspaper reported a farewell 12 PARADE TO GLORY party given for the doctor. The paper said: "It having been announced that Dr. W. M. Fleming was about to leave Rochester and take up his residence in New York, a considerable number of his friends decided to give a complimentary entertainment and invite him to accept the honor. . . . The party having gone through the courses of a splendid supper, moistened with sparkling wine, the feast of reason and flow of soul followed . . . and the evening was protracted until well toward midnight when the party separated." And so the doctor cut his ties in Rochester and moved toward his destiny with the Shrine.

When Dr. Fleming arrived in New York in 1869, he had just received his symbolic Masonic degrees from Rochester Lodge No. 660. He was initiated an Entered Apprentice December 14, 1868, passed to Fellowcraft the following day and raised to the sublime degree of a Master Mason January i i, 1869; and it is apparent that from that time, Masonry more and more dominated his life. It is possible that his interest in fraternalism caused the estrangement of his wife and certainly it alienated the wife of one of his two sons, Dr. Walter S. Fleming.

"My mother opposed my entering the Masons," said the third Walter Fleming, a grandson now living in New York City. "I think she f elt that my grandfather had dissipated a f ortune in the various orders he served." Perhaps he did, for he died virtually penniless though certainly he had an active and lucrative practice in New York for almost forty years. At the 1902 meeting of Albany's class of 1862, Dr. Fleming reported that he had become a qualified examiner in insanity in the Supreme Court of the City of New York, that he was a member of the New York County Medical Society, the Medical‑Legal Society and the Physicians' Mutual Aid. In addition, of course, he practiced extensively among the members of the theatrical profession and was one of the first physicians to be attached to the Actors Fund of America. He wrote extensively on insanity and related subjects, including drug habits and dipsomania. Strangely enough, the only medical paper FROM ALL OF THESE 13 written by him still on file in New York's extensive medical library concerns diseases of the chest, including asthma, for which he believed snuff was not a suitable treatment.

Dr. Fleming's growth in Masonry is almost unbelievable, and most of it can be traced to his interest in and his love of his own Masonic child, the Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. For example, it is notable that at its official birth, the founders of the Shrine decreed that it would be available only to those Masons who had attained the 320 in the Scottish Rite or the Knight Templar degree in the York Rite. Yet, when he wrote the original Ritual, Dr. Fleming had received only his first three basic Masonic degrees.

There can be little doubt that private and informal agreements on the prerequisites for Shrine membership were made among the men who sat at the table for thirteen in Fowler's restaurant and that formal creation of the fun organization would be delayed until Dr. Fleming had obtained them. Accordingly, he received the 4th to 32nd degrees in Brooklyn's Aurora Grata Consistory on May 31, 18 Two weeks later, June 16, 1871, the initial meeting of the founders of the Shrine was held officially in New York's Masonic Hall. On March i q, 1872, Fleming signed the bylaws of Columbian Commandery No. i, thus completing all of the Masonic degrees prior to the official founding of Mecca Temple on September 26, 1872.

Indicating his zeal for Masonry is Fleming's own account, written for the one‑hundredth anniversary conclave in 19 1 o, when he was the oldest living past commander and too ill to attend, of how he literally saved Columbian Commandery from extinction in 1873.

The Commandery was at a low ebb, largely in debt and scantily attended. The proposition of my acceptance of the office of Commander was an astounding surprise. However, through the influence of my offi cial comrades in arms and their persistent insistence, I acceded to their wishes to rescue the oldest Commandery in the state. . . . These ambassadors and advisory council comprised several enthusiastic members of both Commandery and the several bodies of the Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite. I was at this time an enthusiastic worker in all of the grades of Scottish Rite Masonry, and became enthused with the same spirit of 14 PARADE TO GLORY perseverance and success in the Order of Knighthood. I at once proceeded to resuscitate Columbian. Had a "calling of the clans" from all the departments, and supported it to the full with both my counsel and my purse and with renewed zeal devoted all my energies to newly equip the Commandery, increase the roll of membership, arouse a new interest that would defy the angry waves of time and the storm of persecution. . . .

I then proceeded to make the paraphernalia and the work interesting and attractive. I then personally assumed the responsibility of all the monetary requirements. I resumed the usual banquets which had been long abandoned because of lack of funds required to sustain that interesting part of the ceremony. I then proceeded to equip the entire official corps in a full coat of mail armor, helmets, swords, staves, spears, hawbucks, leggings and gauntlets, all of which was strictly authentic and produced by the best costumers in the City of New York. Popularity and success following on the new regime, both officers and members seemed at once to take a new and splendid interest.

Fleming then goes on to relate that he equipped Columbian with a superb silver service and that he spared no expense to obtain the finest in every kind of equipment to make Columbian the acknowl edged leader. At the same time he continued to work in the Scottish Rite, and for the three consecutive years that he served as Commander of C'olumbian was responsible for Knights becoming Scottish Rite Masons and vice versa with the result, as he puts it, that "two separate series of rites or orders ultimately became almost a united family." With all of this, he said, "I found it rather an arduous task to keep pace with all of the requirements in all the complicated ritualistic renditions, official and subordinate, for the several years during which I struggled to equip myself commendably in somewhere near a dozen prominent official positions, including at the same time instituting and fathering of the Order of the Mystic Shrine, the formation of Mecca Temple, first in the City of New York, and many temples following, also the Imperial Council of the Order for the entire jurisdiction of the United States and adjacent territories." The fact is, of course, that Fleming needed Columbian and the Scottish Rite in order to get his own brain child in operation.

FROM ALL OF THESE 15 The second of the four men who created the Shrine was William Jermyn Florence, who was never much more than a so‑so Mason, even after the Shrine came into existence. But he was a real personality. He romped and played across most of America and Europe from the time he first became smitten with the stage. Actor, producer, writer, poet, tune‑smith, comedian, monologuist, playwright‑he was everything in the theater. He loved it and the people loved him.

He was a roly‑poly man‑at least in his later years. He was described by one of his contemporaries as being about five and a half feet tall, and weighing perhaps two hundred pounds. His voice was gentle and musical and his eyes constantly twinkled with mirth. He was an ardent fisherman and made annual pilgrimages to Canada for the salmon.

Florence was born William J. Conlin on July 26, 1831, in Albany, New York, one of a large brood produced by Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Conlin, who had migrated from Ireland. The record of his early life is at the least confusing. Not until he achieved success on the stage did that record attain anything resembling clarity.

Most of the reports of Florence's early life reveal that the C'onlins moved to New York City from Albany about 1845, principally because of better economic opportunities. Eventually most of Florence's brothers obtained employment with the city government, as did many others of Irish descent in those days. One brother, Peter, eventually became a police inspector. Another worked in the street department. But young Billy Conlin would have none of it. At the time of his death in 189 r the New York Times reported that he worked at a mechanical trade, earning enough to help support the family and to provide tickets for the theaters and music halls that abounded. Another story of those years is contained in a book called Songs o f the Florences published by Dick and Fitzgerald in 186o. This story undoubtedly had Florence's approval, and it revealed that "the popular delineator of Irish character was educated at Princeton, N. J., and assumed the active duties of life as a bookkeeper in a well known mercantile house in Burling Slip, New York City." But even though this 16 PARADE TO GLORY revelation may have been approved by Florence, it is to be doubted. There are no records in Princeton that he ever attended any school there and indications are that the family was too poor to afford a private‑school education even for so talented a youngster as Billy Conlin.

During the years from 1845 to 1849 young Conlin began building up for himself something of a reputation for Irish dialect and finally he joined the Murdoch Dramatic Association, a sort of touring stock company, and as Peter in The Stranger he made his first stage appearance in the Richmond Theater in Richmond, Virginia, on December 6, 1849. He was just eighteen years old. And thus began one of the most fabulous careers in all the history of the American stage.

At the close of the 1849 season, Conlin was transferred to New York. He appeared under the management of Brougham and Chippendale at Niblo's theater, Brougham's Lyceum, the Broadway and other theaters of the day, largely in Irish dialect parts, among them that of Dolley in Rob Roy. Sometime during this period, he changed his name to William Jermyn Florence, Florence being his mother's maiden name. Whether he changed his name legally or simply adopted it, was never revealed by Billy himself, but it was as Florence that he lived for the rest of his life, and it was as William J. Florence that he married Malvina Pray on January i, 18 Malvina Pray was a pretty little thing, and was recognized even then as the premiere danseuse of the New York stage. She had first appeared as one of the Pray sisters, but when her sister married Barney Williams, another luminary of the New York theater, Malvina continued alone. It is likely that Florence and Malvina met while they appeared on the same program at Niblo's theater. The marriage resulted in the formation of one of the most famous of all married teams in the theater, comparable today to Lunt and Fontanne. They created The Irish Boy and the Yankee Girl, with which they toured America and Europe for years, and it was while on such a tour that Florence first became a Mason in Philadelphia. The records of Mt. Moriah Lodge No. ░15 5 show that William J. Florence was initiated, passed and raised by virtue of a special dispensation at a special meeting of the lodge on October 12, 185 3. For youngsters, FROM ALL OF THESE 17 Mr. and Mrs. William J. Florence were doing all right. Their biography reports that on this same triumphal tour they received complimentary benefits and services of silver in Baltimore, Washington, New Orleans and Charleston. Pittsburgh also must have been on the itinerary, for on the following June io, 1854, he received his Mark Master degree in Zerubbabel Chapter No. 162. He received his Royal Arch degree two days later. He is listed on the minutes of the chapter as a comedian and classified a sojourner. It was not until December 5, 1855, that he was admitted to Pittsburgh Commandery No. i.

It is obvious from the record of Mt. Moriah Lodge that his interest in Masonry lagged in the ensuing years. He was suspended December 22, 1857, for failure to pay his dues, but was restored to good standing February 24, 1863. He was again suspended December 22, 1868, for failing to pay his dues, but once again paid up on December 26, 1871. It is notable that this restoration came after the first meeting of the original thirteen members of the Shrine and during that period when Dr. Fleming was equipping himself with advanced Masonic degrees. These dates are important in the light of later developments.

Professionally, success followed success for the Florences until, individually and as a team, they became the toasts of the theatrical world, both in the United States and in Europe. They made their first European appearance in London in 1856, playing at the Royal and Drury Lane, and their biographers report that they were frequently visited by the Queen and the royal family. Certainly the Florences received one and perhaps more gifts from the then Prince of Wales.

At home, even during the war years, their success continued, and thus in 186‑7 when it was announced that the Florences again would tour Europe, C. T. McClenachan conceived the idea of making the young actor an ambassador of good will to the Scottish Rite bodies of England. After an agreement with the actor, McClenachan and two other inspectors general of the Scottish Rite in New York conferred the degrees on him at the old Metropolitan Hotel on April 21, under special dispensation. Florence was accredited to Aurora Grata Con‑ 18 PARADE TO GLORY sistory in Brooklyn, with the notation that the actor was about to travel abroad.

What, if anything, Florence ever did for the Scottish Rite is not known, but it was on that trip in 1867 that he set the stage for the famous lawsuit over Caste, a play by an English writer named Robertson. Florence himself related that he was so impressed with it that he visited the theater where it was playing four times, and during those four performances succeeded in memorizing the entire play.

Robertson had sold the American rights to the play to Lester Wallach, owner of Wallach's theater and from time to time Florence's producer and manager, but Florence returned to New York and succeeded in producing the play before Wallach could get it on the boards. Wallach brought suit for damages in a case that Florence eventually won by a Supreme Court decision, which hinged on the fact that there was no international copyright convention. Having won the suit, Florence in a condescending letter to Robertson sent the author a check for fifty pounds, not because he owed it, but because he wanted to be fair. Robertson returned the check with a scathing retort. By and large the New York press thought Florence had perpetrated a rather scurvy affair, but even that failed to dim his popularity‑nor was it ever dimmed.

Charles T. McClenachan, the third important Mason to participate in establishing the Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, was a lawyer of some repute. He had been born in Washing ton, April 13, 1829, but had established his practice in New York, and it was there that he became known as one of the outstanding Masonic ritualists in America. He was an active participant in all branches of the fraternity, and was the active Deputy for the State of New York in the Scottish Rite.

Perhaps more important in the eventual scheme of the Shrine than he was ever given credit for was the fourth important Mason‑William Sleigh Paterson, destined to become the first Recorder of Mecca Temple and of the Imperial Council when it was formed in 1876. Paterson

Charles T. McClenachan was born at Haddington, Scotland, March 6, 1844, and thus was the youngest of all those Masons actively associated with the formation of the Shrine.

Paterson's family migrated to the United States in 1847 where he received his education, which included mastering the French, German, Spanish, Italian, Latin, Greek and Arabic languages, all of which he used as a proofreader in a rather large printing establishment. He received all of his Masonic degrees in New York. He served as secretary of the Scottish Rite bodies of New York from 1872 to 1889. Because of their intimate association over the years, Paterson perhaps knew 20 PARADE TO GLORY Fleming better than anyone else and, because of his knowledge of Arabic, helped more than anyone else in creating the legends of the Shrine.

The fifth man who assisted in the founding of the Shrine was undoubtedly William Fowler the restaurateur, who was not one of the original "13" but rather carried card No. 24 of Mecca Temple. Fowler loved fun and the Shrine was created for fun. William Fowler, Jr., who succeeded to ownership of the famous restaurant, recalled in 1914 in a letter to Saram R. Ellison, Recorder of Mecca Temple, that "from about 18']O to i 88o when my father was proprietor of Knickerbocker Cottage, we had there the Masonic Club. The membership consisted of those prominent in the Scottish Rite, and the first duty of one joining the club was to send his picture to be hung upon the walls of the club room, and we finally had a very valuable collection of pictures. At this time, Dr. Fleming was in the height of his popularity‑as was supported by Charley McClenachan, Henry Banks, George Millar, Bill May, Genl. Roome, D. Northrup and many others of note.

"I distinctly remember on a certain Sunday afternoon, my father coming downstairs and telling me that they were hatching, up in the club, a new order to be called the Mystic Shrine and that in his opin ion unless they got rid of some of the `barnacles,' they would find trouble in starting.

"I know my father was one of the original organizers of the Shrine and it was natural for all hands to meet at his place and `talk it over.' " Of course, after f orty‑four years, young Fowler's memory might leave something to accuracy. Dr. Fleming was new in New York, and he could not possibly have been at the height of his popularity. But there seems to be no doubt that it was at Knickerbocker Cottage that the Shrine was "hatched" and that it was around that table for thirteen that preliminary discussions were held until finally a formal meeting was held on June 16, 1871, at the old Masonic Hall on Thirteenth Street, a meeting at which they could not possibly have foreseen the glorious future of that which they were about to create.

Chapter 3 . . . Better khan they Knew F ANY of the founders of the Shrine could have foreseen in 1871 that the organization eventually would grow to its present astounding size and importance, they would undoubtedly have kept better records. But they didn't and even those records that are available are subject to a certain amount of skepticism. For that reason, much is left to the imagination and a true picture of those early years can be drawn only by deduction from a few facts.

It is young Fowler's letter that really sets the stage for the story of the original "13" meeting around the table in his father's restaurant. It was there, then, that the first discussions must have been held con cerning the new Ritual that Dr. Fleming says‑in his own handwriting ‑he wrote in August of 187 o. How many times they discussed it, how many actual persons read the Ritual, how many were considered to be a part of the inner circle or even the nature of the discussions can only be left to speculation. But there appears to be no question that the first formal meeting of thirteen was held June 16, 187 1. Fleming said so, and so did Paterson. The trouble is that their statements do not dovetail, and if any records of the affair were kept, they have been lost.

In his early history of the meeting, Paterson recalled that it was 21

... BETTER THAN THEY KNEW

23

on that evening that it was decided to confine membership in the Shrine to men who had received advanced Masonic degrees, in either the York or Scottish Rite. On the other hand, Fleming reported to the second annual meeting of the Shrine's Imperial Council in 1877 that it was at the 18‑7 r meeting that the Order was conferred on the thirteen Nobles, including Florence and himself. But at that time, Fleming was not a member of any of the Scottish or York Rite bodies, and it must be assumed that formal organization was delayed until he could acquire the higher degrees. That took something over a year to accomplish, and it was not until September 26, 1872, that Fleming called the original thirteen together again. Invitations were extended to Billy Florence, Sherwood C. Campbell, James S. Chappell, Oswald Merle d'Aubigne, Edward Eddy, Charles T. McClenachan, George W. Millar, John A. Moore, Albert P. Moriarty, William S. Paterson, Daniel Sickels, and John W. Simons. Of these thirteen, who according to Fleming had had the Shrine degree conferred on them at the first meeting in 187 r, only eleven showed up. Florence was presumably on tour, but no reason is given for the absence of Sherwood Campbell.

The i 8 7 2 meeting, like the original one in 18‑71, was held at the old Masonic Hall on Thirteenth Street, and it was there that Mecca Temple, Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, was organized. Finally, at long last, Fleming's dream had come true. And even though vicissitudes of fortune might lie ahead, Fleming was so sure of success that minutes were kept in an old "order" book, still preserved in the Shrine Rooms of the George Washington National Masonic Memorial. These minutes are in Dr. Fleming's handwriting, but are signed by Paterson, who was elected Recorder (secretary) of the infant fraternity.

Strangely enough, the first thirteen sheets of the "order" book in which the minutes were kept have been cut out. There are some who believe those thirteen sheets represented minutes or notations of the 1871 meeting and that, because Fleming was not a member of the higher Masonic orders at that time, he destroyed all records of the session. There are others who believe that the "order" book was sim‑ 24 PARADE TO GLORY ply one that had been used for some entirely different purpose and was used to avoid buying another one.

It was Fleming's Ritual and he called the boys together and thus he presided at the 1872 session. The object, he formally told them, was to form a temple to be known as Mecca, and he started the meeting by reading a letter of advice and instruction from Florence. Unfortunately, that letter or its contents have not been preserved‑nor were its contents inserted into the minutes. If they had been, some of the controversy in later years might have been avoided. Of course the fact is that if such a letter ever existed, Fleming may simply have forgotten it when he wrote the minutes and turned them over to Paterson.

Eight of the eleven members present on September 26, 1872, were elected as officers of Mecca Temple. Fleming, of course, became the Grand Potentate, and it is likely that he had a slate of the other officers prepared that was steam‑rollered through. As the minutes show, those elected were: Charles T. McClenachan, Chief Rabban; John A. Moore, Assistant Rabban; William S. Paterson, Recorder; Edward Eddy, High Priest; James S. Chappell, Treasurer; George W. Millar, Oriental Guide; and Oswald M. d'Aubigne, Captain of the Guard.

The minutes record that the other offices were left vacant until a subsequent meeting "and there being no further business, the Temple was closed in harmony, subject to the call of the Grand Potentate." Dr. Fleming now had his new Order underway. He must have gone home that evening with a sense of pride and fulfillment. But it was not to be easy sailing. Reporting to the Imperial Session in 187 7., Fleming said that after that 1872 organizational meeting "the order remained quiet and inactive until within the past year or more, when on the return of Brother Florence from Europe, where he had witnessed the work exemplified in the most impressive form, he was exceedingly enthusiastic to promote the promulgation of the Order." When Dr. Fleming reported that the Shrine had been quiet and inactive after its formation, he meant just that. The minutes of the meetings of Mecca Temple are quite revealing. The second session of . . BETTER THAN THEY KNEW 25 the temple was not held until January 12, 1874, a year and a half after it was constituted. Again the meeting was held at Masonic Hall on Thirteenth Street, when McClenachan moved that a committee be appointed to revise and perfect the Ritual and to facilitate the exemplification of the Order. The third session was called for December 13, 1875, at the new Masonic Temple on Twenty‑third Street, but a quorum failed to show up, according to the minutes, and so the meeting resolved itself into an informal discussion of matters relative to the Order and "the session closed in harmony." From these minutes and Fleming's own statement that the Order had remained inactive until 1875, it might be presumed that the doctor was too busy with his private practice and his duties in the Colum bian Commandery and Scottish Rite to give much attention to his own brain child. But this is not exactly true. According to James McGee, No. 2 8 in the Mecca Temple roster, Fleming was constantly busy creating new members. In a letter to Saram R. Ellison, Recorder of Mecca Temple, in c q 14, McGee wrote that the Shrine "became general anteroom talk at all Scottish Rite and Commandery gatherings. Fleming kept tab at many of these occasions on scraps of paper, putting them down as regular meetings and in later years styling them as first and second meetings at Masonic Hall, 1 14 East Thirteenth Street. This was where the Scottish Rite held their meetings. . . . These crude memorandums were all in the handwriting of Noble Fleming and were passed over to Noble Paterson, who became Recorder, to dress up with some degree of regularity and arrange as best he could to make a creditable showing. . . . The same looseness prevailed in keeping a record of those on whom Noble Fleming had conferred the Order. The slips or memorandums, same as the so‑called meetings, were handed to Paterson and he collated them the best he could to show connecting links. No f ees were charged. . . . It was natural that errors should creep in, but no one complained, forgetting there was a hereafter." Nevertheless, in the first report of membership, which was not rendered until September of 1876, there were only forty‑three Nobles,

... BETTER THAN THEY KNEW 27 all but six of them in New York City. Furthermore, Fleming reported on the lack of activity in the Shrine during the first four years of Mecca Temple, from the scene and at the time, while McGee wrote from memory when he already was an old man. McGee's letters to Ellison are important because they also reflect on the controversy which developed in later years on the true history of the Shrine. In any event, Fleming called a fourth meeting of Mecca Temple to be held June 6, 1876, at the Masonic Temple in New York, and it was at that meeting that the Imperial Grand Council came into existence. In the light of his own statement of lack of activity and the "exceeding enthusiasm" of Florence to promote the promulgation of the Order, it is to be presumed that Florence called on Fleming after his return from a European tour and said, in effect, "Hey, what gives? Let's get going or drop the whole idea." Fleming got going.

The proceedings of that meeting of Mecca Temple and the formation of the Imperial Grand Council are intact and are rewarding in the light of later developments. These proceedings record that: "Pursuant to a call of the Past Potentates and legally constituted Nobles of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, the following named Nobles of the Order assembled at Masonic Hall, corner of Sixth Avenue and Twenty‑third Street, in the City of New York, N. Y., on Nahar et Talata, the sixteenth day of the fifth Arabic Month, Jamaz ul Awwal, [sic] 1293 A.x., answering to Tuesday, June 6, 1876 A.D., at two o'clock P.M., for the purpose of organizing the Imperial Grand Council of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine for the United States of America." This was the first occasion in the four years since its formation that the Shrine had used any Arabic nomenclature except in the Ritual itself, and even in the Ritual some of the words, phrases and titles that were supposed to give connotations of the Orient were in fact Hebrew rather than Arabic. For example, the titles of Chief and Assistant Rabbans, the second and third highest offices, have no Arabic translation, but in the Hebrew tongue refer to teachers.

Only twenty Nobles (all from Mecca Temple) attended that 2 8 PARADE TO GLORY first session of the Imperial Grand Council. They were Fleming, Paterson, and McClenachan, of course; and, in addition, George W. Millar, John A. Moore, William V. Alexander, John E. Bendix, Edwin Du Laurens, Edward M. L. Ehlers, Peter Forrester, William Fowler, William D. May, Sidney P. Nichols, Aaron L. Northrop, James A. Reed, W. Wallace Walker, J. H. Hobart Ward, all of New York City; George F. Loder, Grand Potentate of Damascus Temple, Rochester, New York; Samuel R. Carter, also of Damascus Temple; and George Scott of Paterson, New Jersey. Mecca members absent at the first Imperial meeting were (according to the proceedings) William J. Florence, Bensen Sherwood, Philip F. Lenhart, Charles P. Marratt, and Angelo Noziglia.

Conspicuous by its absence from the list of those either present or absent is the name of James McGee; for according to the records of Mecca Temple, McGee was just as much a member at that time as any of the rest and around this very point hinges some of the controversy that was to develop in later years. In any event, McGee held card No. 2 8. Marratt held card No. 29, and William D. May, card No. 3o. Also conspicuous by its absence from either list is the name of William T. Hardenbrook, who carried card No. 2 5 and who was the editor of a Masonic newspaper and participated with McGee and others in the controversy over the history of the Shrine.

The official proceedings of the first session of the Imperial Council then report: "A Temple was opened in due form, Illustrious Walter M. Fleming, Grand Potentate of Mecca Temple presiding." Fleming announced the deaths of Sherwood Campbell, James S. Chappell, Oswald d'Aubigne and Edward Eddy, after which "The Imperial Grand Council of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine for the United States of America was then duly organized." Yet that organization just possibly might have been premature. Officially, the only members of the Shrine present were from Mecca Temple and on the face of it there was no real need for a national organization. But Fleming was prepared for any objections that might . . BETTER THAN THEY KNEW 29 arise. He had created Nobles in several other cities, and had given them titles of "Past Potentates" so that they might create their own temples in other cities. And with that in mind, he submitted his slate of candidates for Imperial Grand officers. Those elected were: Walter Al. Fleming, Imperial Grand Potentate; George F. Loder of Rochester, Deputy Grand Potentate; Philip F. Lenhart of Brooklyn, Grand Chief Rabban; Edward M. L. Ehlers, New York, Grand Assistant Rabban; William H. Whiting, Rochester, New York, Grand High Priest and Prophet; Samuel R. Carter, Rochester, New York, Grand Oriental Guide; Aaron L. Northrop, New York, New York, Grand Treasurer; William S. Paterson, New York, New York, Grand Recorder; Albert P. Moriarty, New York, New York, Grand Financial Secretary; John L. Stettimus, Cincinnati, Ohio, Grand First Ceremonial Master; Bensen Sherwood, New York, New York, Grand Second Ceremonial Master; Samuel Harper, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Grand Marshal; Frank H. Bascom, Montpelier, Vermont, Grand Captain of the Guard; and George Scott, Paterson, New Jersey, Grand Outer Guard.

The first meeting of the Imperial Council didn't last long, but there was certain groundwork to be done, and the nobility got right to the task. The officers, or those who were present, were installed by McClenachan, the ritualist, who didn't take an office, presumably because he was too busy with other affairs.

The meeting then took care of the following business: Established New York City as the Grand Orient, or headquarters of the Imperial Council; Approved a plan to create five Past Potentates in each subordinate temple in order that they could be made honorary members of the Imperial Council; Created a committee to write statutes and regulations for the government of the Imperial Council and its subordinate temples, whereupon Fleming appointed McClenachan, Ehlers and Ward to that task; Established fifty dollars as the f ee f or a charter for a new tem‑ 3 0 PARADE TO GLORY ple, ten dollars as the annual temple tax to the Imperial Council, and ten dollars as the minimum initiation fee for each new member; Passed a resolution making it official throughout the United States that all Shriners must be members in good standing of either the Scottish Rite or Knights Templar.

Business completed, the boys dispensed with the reading of the proceedings, closed their session and presumably retired for some of the fun they all expected to have when they became Shriners.

Thus was born an organization which, over the years, though not Masonic, would become the playground and the showcase of Masonry. Trials and tribulations lay ahead. There were days and even years of discouragement for Fleming, for in the infancy of the Shrine, he carried the burden almost alone. There was no exemplification of rites. There was no money, except what Fleming and a few others contributed from their pockets. There were no insignia by which Shriners could be designated. Very simply, Fleming and his associates didn't have much of an inducement for prospective members. Mostly, new members were obtained by personal contact where Fleming's magnetic personality would become the motivating force. But this was too slow. The Shrine would never become great under those circumstances.

Something new was needed, something that would attract prospective Nobles by its glamour and its promise for the future. Thus it was that sometime during the fall and winter of 1876, Fleming began to devise a plan and‑perhaps with the help of Florence, Paterson, McClenachan and others‑to create a legend. He surrounded the Shrine with mysticism as thrilling as the Ritual itself. It was real cloak‑anddagger stuff. And though the stories he told were to be challenged in later years and called figments of his own fertile imagination, they did attract members. Even Fleming changed his stories from time to time, and he made greater use of the great name of Billy Florenceoriginally for the single purpose of promoting the growth of the Shrine. But, since Fleming told his stories with such sincerity, there were many who accepted them as historic fact. Others did not.

... BETTER THAN THEY KNEW 31 Even as late as 1892 when controversy over the legend reached its height, Charles T. McClenachan declared it made no real difference whether the stories might be true and that the Shrine Ritual contained no more myth or fiction than Blue Lodge Masonry, the Chapter, the Commandery or even the Christian religion. McClenachan, who was an authority, held that no ritual need be strictly the truth and that few ever were. But there are always those who insist on absolute truth. They are the ones who say George Washington never chopped down the cherry tree or threw a dollar over the Rappahannock; they are probably right, but history was not damaged by such legends, and if they placed a halo of honesty and strength about the head of Washington, which would reflect itself in the eyes of American youth for generations to come, who is to say the creation of the myth was wrong? Chapter 4 T1te Legend of Arab HE legend of the origin of the Ancient Arabic Order Nobles of the Mystic Shrine begins with the second annual session of the Imperial Grand Council, held at the Masonic Temple in Albany, New York, February 6, 1877. The legend was given voice by Dr. Fleming in his first annual address, reporting on his activities. The circumstances of how he arrived at the content of the speech delivered that cold winter day, climatically so different from the hot sands of the strange Islamic world of the Arabs, are lost, if they were ever known, but it was the first effort to surround the new American order with authentic antiquity.

"It is some five years," Dr. Fleming said, "since I came into possession of detached and mutilated sections of the translation of the Ritual of the Arabic and Egyptian Order of the Mystic Shrine, brought to America by one of the foreign members and representatives, through the hands of Brother Oswald Merle D'Aubigne, 32░. It was exceedingly imperfect and incomplete and to a great extent badly translated and filled with unintelligible symbolisms. Another portion was brought from Oriental Europe by 111. Brother William J. Florence, 320 and some of the vague history and Ritualistic sections were brought from Cairo, Egypt, by Ill. Brother Sherwood C. 32 THE LEGEND OF ARABY 3 3 Campbell, 320. Those portions in the possession of Brother Florence were marked, and referred to certain sections of the Koran for notes and allusions, which greatly facilitated the compiling and revising of the Ritual to its present completion.

"This was a task of no small magnitude, and was undertaken and completed through the efforts of Brother Florence and myself, aided by a professional linguist and Arabic scholar." Just whom Fleming meant in his reference to a professional linguist and Arabic scholar is not known. It might have been Paterson, who did know some Arabic; but as it later developed, it probably was Albert L. Rawson, an artist who had illustrated several books dealing with early Mediterranean religions. Rawson was not a Shriner at the time but became one later and participated actively with Fleming in publicizing the Order.

Fleming, in his address, went on to relate the circumstances and dates of the founding of Mecca Temple and the formation of the Imperial Council, and then he said: "The original plate engravings, for the production of Dispensations, Charters and Diplomas of the Imperial Grand Council, were executed in Paris, France, and the designs were taken from the arches and gateways of the Egyptian Temple of the Sun. The printing and colored transfers were perfected in the City of New York, where also the Statutes and Ritual were printed and the Grand Seal procured." Only a few copies of the original charters are still in existence. Some of them have been destroyed by fire, and others have been lost. Those extant are really works of art, and may well have been the product of Rawson, some of whose art work, illustrating a volume on the Eleusinian theory of esoteric religion, is similar in style to the original charters.

Fleming also reported in 1877 on more earthy problems. He said that the work since the formation of Mecca Temple had involved both a large expenditure and accruing indebtedness; but, he said, a few hundred dollars would place the Imperial Grand Council out of 3 4 PARADE TO GLORY debt f or the obligations of the past. It is noteworthy that Fleming contributed most of the expenses of the formation of the Order, and that he was not to be repaid the advances for a number of years.

But the Shrine was growing, Fleming reported. The second temple to be formed was Damascus at Rochester, but dispensations also had been granted to Al Koran in Cleveland, Syrian in Cincinnati, Mount 'Sinai in Montpelier, Vermont, and Naja and Cyprus in Albany.

The good doctor may or may not have been slightly embarrassed by some of the report he had to make. He said, for example: "All who have received the Order are evidently exceedingly well pleased with the impressiveness of the Ritualistic work and the sublime tenets of the Order. It could no doubt be made a most powerful Order, devoted to the welfare of Masonry in this country.

"Mecca Temple," Dr. Fleming said, "is not exemplifying the work at present, as the matter was left entirely to one or two others and myself, and my time has been so fully occupied with the duties of Most Illustrious Grand Potentate, in promoting the establishment of temples, and the various requirements of the Imperial Grand Council, that it was impossible for me to carry on the work at home in a subordinate temple." Dr. Fleming also explained that he thought the Shrine should be exclusive.

"It has been the desire," he said, "of the Grand Council as well as the membership subordinate to make it a select Order, uncontaminated with discordant elements and unworthy membership. There should be at least one branch of Ancient Craftsmen, select and free of the inappreciative and the unworthy. We trust, therefore, that, as it is a consummation most devoutly to be wished for, all will proceed with care, caution and judgment, in regard to whom they honor with admission." By and large, it was the most successful meeting of the Shrine to that time. It had taken Fleming six long years to bring the infant Order thus far, but he could return to his medical practice in New THE LEGEND OF ARABY 35 York, confident that the new fraternity was on its way. It was to grow beyond the wildest imaginations of its founders, who "builded better than they knew" in the early days. Certainly one of the factors of that building was the aura of Oriental mysticism that Fleming had injected at the Albany session.

A half‑century later, McGee declared that Fleming eventually regretted having mentioned the story of the Ancient Arabic manuscripts; but upon his return to New York from Albany he wrote or with Paterson helped to write the "origin and history" of the Order, which was included in a brochure obviously designed to spread and build it. It contained the statutes and regulations which had been adopted in Albany and full particulars on how new temples could be established. But the important part of the brochure was the embellishment of the legend. This 1877 brochure, which was found among the Paterson papers, reports: The Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine was established in Mecca, Arabia, and became an acknowledged power in the year 5459, equivalent to the year of Our Lord 1698.

The Ritual was compiled and arranged at Aleppo, Arabia, and issued by Louis Marracci, the great Latin translator of Mohammed's Al Koran. This mysterious Order continued to thrive in Arabia from that date to the present time. It was revised and instituted at Cairo, Egypt, in 5598, equivalent to June 14, 1837.

The Order was primarily instituted for the purpose of promoting the organization and perfection of Arabic and Egyptian inquisitions, to dispense justice, and execute punishment of criminals whom the tardy laws did not reach to the measure of their crimes. Being designed to embrace the entire pale of the law, and composed of sterling and determined men who would upon a valid accusation fearlessly try, judge, and if convicted, execute the criminal within the hour‑leaving no trace of their acts behind. . . .

More recent history informs us that Oriental Europe is permeated with secret organizations, comprising a selection of the highest and best educated classes of the Mussulman nations; their ostensible object being "the strife of Islam or Mohammedanism against the infidels"; and among the latter are supposed to be included Christians, Israelites, Mussulman 3 6 PARADE TO GLORY princes and potentates, who are suspected, together with the Khedive of Egypt, of being favorable to Christian institutions.

The most prominent and powerful of these orders is the Bektashy, or Nobles of the Mystic Shrine. Its offshoots and satellites are the Darkawy, Khowan, Ab Del Kader El Bagdadi, and the Issawiye, similar in obligation and purpose. These are not altogether politico‑religious societies as generally supposed by the outside world. Although ostensibly appearing as such there is a deep and hidden meaning beneath the exposed superficial exterior, as promulgated to the profane.

These orders are closely allied to the famous "Illuminati," which fraternity exercised such vigilant power during the reign of King Frederick William of Prussia.

The real object of all of these Orders is to gain all possible power of reign and rule; to exercise these powers for the best welfare of country or land; and to fearlessly purify it of all base and sordid element of whatever nature, independent of creed, sect or nationality; their foundation being the acknowledgment of Deity or one ever‑loving and true God....

The Bektashy, or Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, as it is known in America, is of necessity divested of its inconsistent Islam dogmas and its ritual adapted to the consistencies of Christian institutions and American laws, and is destined to become a powerful order here in America.

Its jewel of membership, or the insignia of the order worn by its disciples, is the Crescent, formed by the claws of a tiger, united at the bases and bound with gold, bearing the additional emblems of the head of a female Sphinx, on one side and a pyramid, urn, and star upon the other, also bearing the date of the reception of the order and the Latin motto "Robur et Furor"‑signifying strength and fury.

This particular history then includes considerable detail concerning the origin of the Crescent as a symbol of power and authority, and it goes on to say: In i 8o i the Sultan Selim 111, having previously presented Lord Nelson with a crescent richly adorned with diamonds, founded the Order of the Crescent, which, as Mohammedans are not allowed to carry such marks of distinction, has been conferred on Christians alone.

Temples of the Order of the Crescent, or Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, were instituted in various cities of Europe many years ago, and now, although possessing all the powers, material and paraphernalia of THE LEGEND OF ARABY 3 7 the Inquisition, if required, still continue to thrive as social and charitable organizations, impressing on its disciples its purifying tenets and attributes, while always on the alert to arouse into executive action should an emergency arise.

In 1871 the Ritual was brought to America by one of the transient foreign members and representatives with instructions to place it only in the hands of prominent high‑grade Masons for establishment and exemplification as had been done in Europe. Owing to the fact of Masons being regarded as a choice of the best men in the land, and having already passed the ordeal of obligation, the Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine would be regarded as safer with them than with the unobligated masses, and make it, if necessity required, a deliberating and executive body of inquisitorial nature, as when originally inaugurated.

The 1877 history is similar in content, but not in style or spelling, to a history of the Order printed in 1893 which had been "compiled and collated" by Fleming and Paterson, and it is this latter "or igin of the Order" which over the years has been most quoted. In 1902, Fleming wrote a letter to George L. Root of Mohammed Temple, Peoria, Illinois, authorizing him to use the later version in a book he was preparing. Fleming wrote: "I am in receipt of yours of the 13th inst. relative to using my `History of the Shrine.' Personally I have no objections, especially if for distribution to the Nobles of the Order. I do not think Noble Paterson would object either if credited to its authors." The legend of the Shrine became permanent with the publication of this later history. It probably was written in 1883 while Fleming was still the Imperial Potentate, for it is mentioned in the official proceedings of that year, but the first known publication came in a pamphlet issued by Imperial Recorder Frank Luce, who had succeeded Paterson. It is dated 1893.

That history says: The Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine was instituted by the Mohammedan Kalif Alee (whose name be praised!), the cousin‑german and son‑in‑law of the Prophet Mohammed (God favor and preserve him!), in the year of the Hegira 25 (A.D. 644) at Mecca in Arabia, as an inquisition, or Vigilance Committee, to dispense justice and execute punish‑ 3 8 PARADE TO GLORY ment upon criminals who escaped their just deserts through the tardiness of the courts, and also to promote religious tolerance among cultured men of all nations. The original intention was to form a band of men of sterling worth who would, without fear or favor, upon a valid accusation, try, judge, and execute, if need be, within the hour, having taken precautions as to secrecy and security.

The "Nobles" perfected their organization, and did such prompt and efficient work that they excited alarm and even consternation in the hearts of evildoers in all countries under the Star and Crescent.

The Order is yet one of the most highly favored among the many secret societies which abound in Oriental countries, and gathers around its shrines a select few of the best educated and cultured classes. Their ostensible object is to increase the faith and fidelity of all true believers in Allah (whose name be exalted!). The secret and real purpose can only be made known to those who have encircled the Mystic Shrine according to instructions in "The Book of the Constitution and the Regulations of the Imperial Council." Its membership in all countries includes Christians, Israelites, Moslems and men in high positions of learning and power. One of the most noted patrons of the Order was the late Khedive of Egypt (whose name be revered!) whose inclination toward Christians is well known.

The Nobles of the Mystic Shrine was sometimes mistaken for a certain order of the dervishes, such as those known as the Hanafeeyeh, Rufaeeyeh, Sadireeyeh, and others, either howling, whirling, dancing or barking; but this is an error. The only connection that the Order ever had with any sect of dervishes was with that called the Bektash. This warlike sect undertook to favor and protect the Nobles in a time of great peril, and have ever since been counted among its most honored patrons.

The famous Arab known as Bektash, from a peculiar high white hat or cap which he made from a sleeve of his gown, the founder of the sect named in his honor, was an imam in the army of the Sultan Amu rath 1, the first Mohammedan who led an army into Europe, A.D. 136o (in the year of the Hegira, 761). This Sultan was the founder of the military order of the Janizaries (so called because they were freed captives who were adopted into the faith and the army), although his father Orkham began the work. Bektash adopted a white robe and cap, and instituted the ceremony of kissing the sleeve.

The Buktasheeyeh's representative at Mecca is a Noble of the Mystic Shrine, is the chief officer of the Alee Temple of Nobles, and in 187'7 was the chief of the Order in Arabia. The chief must reside either at THE LEGEND OF ARABY 39 Mecca or Medinah, and, in either case must be present in person or by deputy during the month of pilgrimage.

The character of the Order as it appears to the uninitiated is that of a politico‑religious society. It is really more than such a society could be; and there are hidden meanings in its simplest symbols that take hold on the profoundest depths of the heart.

Among the modern promoters of the principles of the Order in Europe, one of the most noted was Herr Adam Weishaupt, a Rosicrucian (Rose Cross Mystic), and professor of law in the University of Ingol stadt, in Bavaria, who revived the Order in that city on May 1, 1776. Its members exercised a profound influence before and during the French Revolution, when they were known as the Illuminati, and they professed to be teachers of philosophy. From the central society at Ingolstadt, branches spread through all Europe. Among the members, there are recorded the names of Frederick the Great, Mirabeau, a Duke of Orleans, many members of royal families, literary, scientific and professional men, including the illustrious Goethe, Spinoza, Kant, Lord Bacon, and a long list besides, whose works enlarge and free the mind from the influence of dogma and prejudice.

Frequent revolutions in Arabia, Persia and Turkey have obscured the Order from time to time, as appears from the many breaks in the continuity of the records at Mecca, but it has often been revived. Some of the most noted revivals are those at Mecca and Aleppo in A.D. 1698 (A.x. i i io) and at Cairo in 1837 (A.x. 1z53), the latter under the protection of the Khedive of Egypt, who recognized the Order as a powerful means of civilization.

In the year A.D. 804, during a warlike expedition against the Byzantine emperor Nikephorous, the most famous Arabian Kalif, Haroon alRasheed, deputed a renowned scholar, Abd el‑Kader el‑Bagdadee, to proceed to Aleppo, Syria and found a college there for the propagation of the religion of the Prophet Mohammed (God favor and preserve him!). The work and college arose and the Order of Nobles was revived there as a part of the means of civilization.

The Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine in America does not advocate Mohammedanism as a sect, but inculcates the same respect to Deity here as in Arabia and elsewhere, and hence the secret of its profound grasp on the intellect and the heart of all cultured people.

The Ritual now in use is a translation from the original Arabic, found preserved in the archives of the Order at Aleppo, Syria, whence it was brought in 186o, to London, England, by Rizk Allah Hassoon 40 PARADE TO GLORY Effendi, who was the author of several works in Arabic, one of which was a metrical version of the Book of Job. His "History of Islam" offended the Turkish government because of its humanitarian principles, and he was forced to leave his native country.

In the year 1698, the learned Orientalist, Luigi Marracci, who was then just completing his great works, "The Koran in Latin and Arabic with notes," and "The Bible in Arabic" at Padua, Italy, was initiated into our Order of Nobles, and found time to translate the Ritual into Italian. The initiated will be able to see how deeply significant this fact is when the history of the Italian society of "Carbonari" is recalled. The very existence of Italian unity and liberty depended largely on the "Nobles" who were represented by Count Cavour, Mazzini, Garibaldi and the king, Victor Emmanuel.