Note: This material was scanned into text files for the sole purpose of convenient electronic research. This material is NOT intended as a reproduction of the original volumes. However close the material is to becoming a reproduced work, it should ONLY be regarded as a textual reference. Scanned at Phoenixmasonry by Ralph W. Omholt, PM in May 2007.

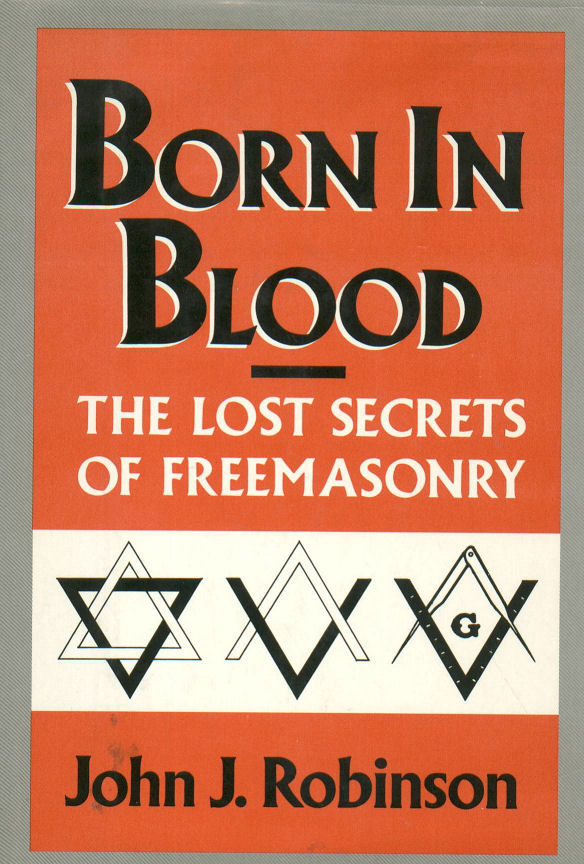

BORN IN BLOOD

THE LOST SECRETS

OF FREEMASONRY

By John J. Robinson

Its mysterious symbols and rituals had been used in secret for centuries before Freemasonry revealed itself in London in 1717. Once known, Freemasonry spread throughout the world and attracted kings, emperors, and statesmen to take its sacred oaths. It also attracted great revolutionaries such as George Washington and Sam Houston in America, Juarez in Mexico, Garibaldi in Italy, and Bolivar in South America. It was outlawed over the centuries by Hitler, Mussolini, and the Ayatollah Khomeini. But where had this powerful organization come from? What was it doing in those secret centuries before it rose from underground more than 270 years ago? And why was Freemasonry attacked with such intense hatred by the Roman Catholic church?

This amazing detective story answers those questions and proves that the Knights Templar in Britain, fleeing arrest and torture by pope and king, formed a secret society of mutual protection that came to be called Freemasonry. Based on years of meticulous research, this book solves the last remaining mysteries of the Masons‑‑their secret words, symbols, and allegories whose true meanings had been lost in antiquity. With a richly drawn background of the bloody battles, the opportunistic kings and scheming popes, the tortures and religious persecution that were the Middle Ages, it is an important book that may require that we take a new look at the history of events leading to the Protestant Reformation.

JOHN J. ROBINSON is a writer with special interest in the history of Medieval Britain and the Crusades. He heads a family trust dedicated to historical research and publication. A business executive, sheep farmer, and ex‑Marine, Mr. Robinson is also a member of the Medieval Academy of America, the Organization of American Historians, and the Royal Oversees League of London. He lives in Carroll County, Kentucky.

Contents

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction: In Search of the Great Society xi

Part 1: THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR

CHAPTER 1: The Urge To Kill 3

CHAPTER 2: "For Now Is Tyme To Be War" 17

CHAPTER 3: "Whether Justly or Out of Hate" 37

CHAPTER 4: "First, and Above All . . . The Destruction of the Hospitallers" 46

CHAPTER 5: The Knights of the Temple 63

CHAPTER 6: The Last Grand Master 79

CHAPTER 7: "The Hammer of the Scots" 99

CHAPTER 8: Four Vicars of Christ 116

CHAPTER 9: "Spare No Known Means of Torture" 127

CHAPTER 10: "No Violent Effusions of Blood" 144

CHAPTER 11: Men on the Run 159

Part 2: THE FREEMASONS

Prologue 173

CHAPTER 12: The Birth of Grand Lodge 175

CHAPTER 13: In Search of the Medieval Guilds 188

CHAPTER 14: "To Have My Throat Cut Across" 201

CHAPTER 15: "My Breast Torn Open, My Heart Plucked Out" 210

CHAPTER 16: The Master Mason 215

CHAPTER 17: Mystery in Language 224

CHAPTER 18: Mystery in Allegory and Symbols 235

CHAPTER 19: Mystery in Bloody Oaths 246

CHAPTER 20: Mystery in Religious Convictions 255

CHAPTER 21: Evidence in the Legend of Hiram Abiff 269

CHAPTER 22: Monks into Masons 277

CHAPTER 23: The Protestant Pendulum 291

CHAPTER 24: The Manufactured Mysteries 305

CHAPTER 25: The Unfinished Temple of Solomon 325

Appendix: "Humanum Genus" 345

Bibliography 360

Index 366

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to the Reverend Martin Chadwick, M.A., Rural Dean of Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire, who obtained permission for me to use the Bodleian Library and its Radcliffe Camera at Oxford University in England. In that same locale, special thanks must also be expressed to Dr. Maurice Keen of Balliol College, who took time from his crowded schedule for a tutorial session with an amateur American historian. His insights into aspects of the Peasants' Revolt and of the teachings of John Wycliffe and of the Lollard Knights provided fresh starting points for research. The willing assistance of librarians is too often overlooked, so I would like to express appreciation for the helpful attitudes of the staff members of the libraries in Oxford and Lincoln in England, as well as those of New York's Forty-second Street library and the public library of Cincinnati. I was also given most gracious treatment at the county archives of Oxfordshire and at the Lincolnshire County Museum.

Recognition should also be given to a number of Freemasons of various degrees who shared with me not the "secrets" of the order, but rather their understandings of the origins and purposes of the fraternity as expressed to them by Masonic writers and lecturers.

It should be noted that although I received a great deal of generous help, the opinions expressed and the conclusions reached in this book are my own.

As for the contributions of my wife, they are difficult to enumerate. The manuscript was not just typed but reviewed for clarity as well as for accuracy of dates and geography. She assisted infour years of research and enthusiastically discussed the outline and content of each chapter. Her knowledge of French eased that aspect of the research, and most of the sources in England came as a result of the friends and contacts she had made over a period of years as an educator in Oxfordshire.

Finally, a word of explanation about the dedication of this book. J. R. Wallin is not a "Master Craftsman" in the symbolic Masonic sense but is literally a master worker in iron and steel. During working hours his forge turns out decorative iron gates and brackets and furniture, but in his spare time it gives way to his fascination with the medieval period by producing such items as a mace, a dagger, or a jousting helmet. The hours spent with him talking about the Crusades and the Templars helped to keep up my enthusiasm for the project. I chose to dedicate this book to him because I think we should all encourage rare breeds, and there can't be many people left on this earth who spend winter evenings interlocking thousands of handmade loops to create a coat of chain mail.

John J. Robinson Twin Brook Farm Carroll County, Kentucky

Introduction

In Search of the Great Society

The research behind this book was not originally intended to reveal anything about Freemasonry or the Knights Templar. Its objective had been to satisfy my own curiosity about certain unexplained aspects of the Peasants' Revolt in England in 1381, a savage uprising that saw upwards of a hundred thousand Englishmen march on London. They moved in uncontrolled rage, burning down manor houses, breaking open prisons, and cutting down any who stood in their way.

One unsolved mystery of that revolt was the organization behind it. For several years a group of disgruntled priests of the lower clergy had traveled the towns, preaching against the riches and corruption of the church. During the months before the uprising, secret meetings had been held throughout central England by men weaving a network of communication. After the revolt was put down, rebel leaders confessed to being agents of a Great Society, said to be based in London. So very little is known of that alleged organization that several scholars have solved the mystery simply by deciding that no such secret society ever existed.

Another mystery was the concentrated and especially vicious attacks on the religious order of the Knights Hospitaller of St. John, now known as the Knights of Malta. Not only did the rebels seek out their properties for vandalism and fire, but their prior

xii BORN IN BLOOD

was dragged from the Tower of London to have his head struck off and placed on London Bridge, to the delight of the cheering mob.

There was no question that the ferocity unleashed on the crusading Hospitallers had a purpose behind it. One captured rebel leader, when asked the reasons for the revolt, said, "First, and above all ... the destruction of the Hospitallers." What kind of secret society could have had that special hatred as one of its primary purposes?

A desire for vengeance against the Hospitallers was easy to identify in the rival crusading order of the Knights of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. The problem was that those Knights Templar had been completely suppressed almost seventy years before the Peasants' Revolt, following several years during which the Templars had been imprisoned, tortured, and burned at the stake. After issuing the decree that put an end to the Templar order, Pope Clement V had directed that all of the extensive properties of the Templars should be given to the Hospitallers. Could a Templar desire for revenge actually have survived underground for three generations?

There was no incontrovertible proof, yet the only evidence suggests the existence of just one secret society in fourteenth century England, the society that was, or would become, the order of Free and Accepted Masons. There appeared to be no connection, however, between the revolt and Freemasonry, except for the name or title of its leader. He occupied the center stage of English history for just eight days and nothing is known of him except that he was the supreme commander of the rebellion. He was called Walter the Tyler, and it seemed at first to be mere coincidence that he bore the title of the enforcement officer of the Masonic lodge. In Freemasonry the Tyler, who must be a Master Mason, is the sentry, the sergeant‑at‑arms, and the officer who screens the credentials of visitors who seek entrance to the lodge. In remembrance of an earlier, more dangerous time, his post is just outside the door of the lodge room, where he stands with a drawn sword in his hand.[ Traditionally, a “flaming sword;” which guards the tree of Life (Qabbalah???)]

I was aware that there had been many attempts in the past to link the Freemasons with the Knights Templar, but never with success. The fragile evidence advanced by proponents of that connection had never held up, sometimes because it was based

INTRODUCTION xlil

on wild speculation, and at least once because it had been based on a deliberate forgery. But despite the failures to establish that link, it just will not go away, and the time‑shrouded belief in some relationship between the two orders remains as one of the more durable legends of Freemasonry. That is entirely appropriate, because all of the various theories of the origins of Freemasonry are legendary. Not one of them is supported by any universally accepted evidence. I was not about to travel down that time‑worn trail, and decided to concentrate my efforts on digging deeper into the history of the Knights Templar, to see if there was any link between the suppressed Knights and the secret society behind the Peasants' Revolt. In doing so, I thought that I would be leaving Freemasonry far behind. I couldn't have been more mistaken.

Like anyone curious about medieval history, I had developed an interest in the Crusades, and perhaps more than just an interest. Those holy wars hold an appeal that is frequently as romantic as it is historical, and in my travels I had tried to drink in the atmosphere of the narrow defiles in the mountains of Lebanon through which Crusader armies had passed, and had sat staring at the castle ruins around Sidon and Tyre, trying to hear the clashing sounds of attack and defense. I had marveled at the walls of Constantinople and had strolled the Arsenal of Venice, where Crusader fleets were assembled. I had sat in the round church of the Knights Templar in London, trying to imagine the ceremony of its consecration by the Patriarch of Jerusalem in 1185, more than three hundred years before Columbus set sail west to the Indies.

The Templar order was founded in Jerusalem in 1118, in the aftermath of the First Crusade. Its name came from the location of its first headquarters on the site of the ancient Temple of Solomon. Helping to fill a desperate need for a standing army in the Holy Land, the Knights of the Temple soon grew in numbers, in wealth, and in political power. They also grew in arrogance, and their Grand Master de Ridfort was a key figure in the mistakes that led to the fall of Jerusalem in 1187. The Latin Christians managed to hold onto a narrow strip of territory along the coast, where the Templars were among the largest owners of the land and fortifications.

Finally, the enthusiasm for sending men and money to the

xlv BORN IN BLOOD

Holy Land waned among the European kingdoms, which were preoccupied with their wars against each other. By 1296 the Egyptian sultan was able to push the resident Crusaders, along with the military orders, into the sea. The Holy Land was lost, and the defeated Knights Templar moved their base to the island kingdom of Cyprus, dreaming of yet one more Crusade to restore their past glory.

As the Templars planned a new Crusade against the infidel, King Philip IV of France was planning his own private crusade against the Templars. He longed to be rid of his massive debts to the Templar order, which had used its wealth to establish a major banking operation. Philip wanted the Templar treasure to finance his continental wars against Edward I of England.

After two decades of fighting England on one side and the Holy Roman Church on the other, two unrelated events gave Philip of France the opportunity he needed. Edward I died, and his deplorably weak son took the throne of England as Edward II. On the other front, Philip was able to get his own man on the Throne of Peter as Pope Clement V.

When word arrived on Cyprus that the new pope would mount a Crusade, the Knights Templar thought that their time of restoration to glory was at hand. Summoned to France, their aging grand master, Jacques de Molay, went armed with elaborate plans for the rescue of Jerusalem. In Paris, he was humored and honored until the fatal day. At dawn on Friday, the thirteenth of October, 1307, every Templar in France was arrested and put in chains on Philip's orders. Their hideous torture for confessions of heresy began immediately.

When the pope's orders to arrest the Templars arrived at the English court, young Edward II took no action at all. He protested to the pontiff that the Templars were innocent. Only after the pope issued a formal bull was the English king forced to act. In January, 1308, Edward finally issued orders for the arrest of the Knights Templar in England, but the three months of warning had been put to good use. Many of the Templars had gone underground, while some of those arrested managed to escape. Their treasure, their jeweled reliquaries, even the bulk of their records, had disappeared. In Scotland, the papal order was not even published. Under those conditions England. and especially Scotland, became targeted havens for fugitive Templars from continental

INTRODUCTION xv

Europe, and the efficiency of their concealment spoke to some assistance from outside, or from each other.

The English throne passed from Edward II to Edward III, who bequeathed the crown to his ten‑year‑old grandson who, as Richard II, watched from the Tower as the Peasants' Revolt exploded throughout the City of London.

Much had happened to the English people along the way. Incessant wars had drained most of the king's treasury and corruption had taken the rest. A third of the population had perished in the Black Death, and famine exacted further tolls. The reduced labor force of farmers and craftsmen found that they could earn more for their labor, but their increased income came at the expense of land‑owning barons and bishops, who were not prepared to tolerate such a state of affairs. Laws were passed to reduce wages and prices to pre-plague levels, and genealogies were searched to re-impose the bondage of serfdom and villeinage on men who thought themselves free. The king's need for money to fight his French wars inspired new and ingenious taxes. The oppression was coming from all sides, and the pot of rebellion was brought to the boil.

Religion didn't help, either. The landowning church was as merciless a master as the landowning nobility. Religion would have been a source of confusion for the fugitive Templars as well. They were a religious body of warrior monks who owed allegiance to no man on earth except the Holy Father. When their pope turned on them, chained them, beat them, he broke their link with God. In fourteenth‑century Europe there was no pathway to God except through the vicar of Christ on earth. If the pope rejected the Templars and the Templars rejected the pope, they had to find a new way to worship their God, at a time when any variation from the teachings of the established church was blasted as heresy.

That dilemma called to mind the central tenet of Freemasonry, which requires only that a man believe in a Supreme Being, with no requirements as to how he worships the deity of his choice. In Catholic Britain such a belief would have been a crime, but it would have accommodated the fugitive Templars who had been cut off from the universal church. In consideration of the extreme punishment for heresy, such an independent belief also made sense of one of the more mysterious of Freemasonry's Old

xvl BORN IN BLOOD

Charges, the ancient rules that still govern the conduct of the fraternity. The Charge says that no Mason should reveal the secrets of a brother that may deprive him of his life and property.

That connection caused me to take a different look at the Masonic Old Charges. They took on new direction and meaning when viewed as a set of instructions for a secret society created to assist and protect fraternal brothers on the run and in hiding from the church. That characterization made no sense in the context of a medieval guild of stonemasons, the usual claim for the roots of Freemasonry. It did make a great deal of sense, however, for men such as the fugitive Templars, whose very lives depended upon their concealment. Nor would there have been any problem in finding new recruits over the years ahead: There were to be plenty of protestors and dissidents against the church among future generations. The rebels of the Peasants' Revolt proved that when they attacked abbeys and monasteries, and when they cut the head off the Archbishop of Canterbury, the leading Catholic prelate in England.

The fugitive Templars would have needed a code such as the Old Charges of Masonry, but the working stonemasons clearly did not. It had become obvious that I needed to know more about the Ancient Order of Free and Accepted Masons. The extent of the Masonic material available at large public libraries surprised me, as did the fact that it was housed in the department of education and religion. Not content with just what was generally available to the public, I asked to use the library in the Masonic Temple in Cincinnati, Ohio. I told the gentleman there that I was not a Freemason, but wanted to use the library as part of my research for a book that would probably include a new examination of the Masonic order. His only question to me was, "Will it be fair?" I assured him that I had no desire or intention to be anything other than fair, to which he replied, "Good enough." I was left alone with the catalog and the hundreds of Masonic books that lined the walls. I also took advantage of the publications of the Masonic Service Association at Silver Spring, Maryland.

Later, as my growing knowledge of Masonry enabled me to sustain a conversation on the subject, I began to talk to Freemasons. At first I wondered how I would go about meeting fifteen or twenty Masons and, if I could meet them, would they be willing to talk to me? The first problem was solved as soon as I started asking

INTRODUCTION xvll

friends and associates if they were Masons. There were four in one group I had known for about five years, and many more among men I had known for twenty years and more, without ever realizing that they had any connection with Freemasonry. As for the second part of my concern, I found them quite willing to talk, not about the "secret" passwords and hand grips (by then, I already knew them), but about what they had been taught concerning the origins of Freemasonry and its ancient Old Charges.

They were as intrigued as I was about the possibilities of discovering the lost meanings of words, symbols, and ritual for which no logical explanation was available, such as why a Master Mason is told in his initiation rites that "this degree will make you a brother to pirates and corsairs." We agreed that unlocking the secrets of those Masonic mysteries would contribute most to unearthing the past, because the loss of their true meanings had caused the ancient terms and symbols to be preserved intact, less subject to change over the centuries, or by adaptations to new conditions.

Among those lost secrets were the meanings of words used in the Masonic rituals, words like tyler, cowan, due‑guard, and Juwes. Masonic writers have struggled for centuries, without success, to make those words fit with their preconceived conviction that Masonry was born in the English‑speaking guilds of medieval stonemasons.

Now I would test the possibility that there was indeed a connection between Freemasonry and the French‑speaking Templar order, by looking for the lost meanings of those terms, not in English, but in medieval French. The answers began to flow, and soon a sensible meaning for every one of the mysterious Masonic terms was established in the French language. It even provided the first credible meaning for the name of Hiram Abiff, the murdered architect of the Temple of Solomon, who is the central figure of Masonic ritual. The examination established something else as well. It is well known that in 1362 the English courts officially changed the language used for court proceedings from French to English, so the French roots of all the mysterious terms of Freemasonry confirmed the existence of that secret society in the fourteenth century, the century of the Templar suppression and the Peasants' Revolt.

With that encouragement I addressed other lost secrets of Masonry: the circle and mosaic pavement on the lodge room

xvlii BORN IN BLOOD

floor, gloves and lambskin aprons, the symbol of the compass and the square, even the mysterious legend of the murder of Hiram Abiff. The Rule, customs, and traditions of the Templars provided answers to all of those mysteries. Next came a deeper analysis of the Old Charges of ancient Masonry that define a secret society of mutual protection. What the "lodge" was doing was assisting brothers in hiding from the wrath of church and state, providing them with money, vouching for them with the authorities, even providing the "lodging" that gave Freemasonry the unique term for its chapters and their meeting rooms. There remained no reasonable doubt in my mind that the original concept of the secret society that came to call itself Freemasonry had been born as a society of mutual protection among fugitive Templars and their associates in Britain, men who had gone underground to escape the imprisonment and torture that had been ordered for them by Pope Clement V. Their antagonism toward the Church was rendered more powerful by its total secrecy. The suppression of the Templar order appeared to be one of the biggest mistakes the Holy See ever made.

In return, Freemasonry has been the target of more angry papal bulls and encyclicals than any other secular organization in Christian history. Those condemnations began just a few years after Masonry revealed itself in 1717 and grew in intensity, culminating in the bull Humanum Genus, promulgated by Pope Leo XIII in 1884. In it, the Masons are accused of espousing religious freedom, the separation of church and state, the education of children by laymen, and the extraordinary crime of believing that people have the right to make their own laws and to elect their own government, "according to the new principles of liberty." Such concepts are identified, along with the Masons, as part of the kingdom of Satan. The document not only defines the concerns of the Catholic Church about Freemasonry at that time, but, in the negative, so clearly defines what Freemasons believe that I have included the complete text of that papal bull as an appendix to this book.

Finally, it should be added that the events described here were part of a great watershed of Western history. The feudal age was coming to a close. Land, and the peasant labor on it, had lost its role as the sole source of wealth. Merchant families banded into guilds, and took over whole towns with charters as municipal

INTRODUCTION xlx

corporations. Commerce led to banking and investment, and towns became power centers to rival the nobility in wealth and influence.

The universal church, which had fought for a position of supremacy in a feudal context, was slow to accept changes that might affect that supremacy. Any material disagreement with the church was called heresy, the most heinous crime under heaven. The heretic not only deserved death, but the most painful death imaginable.

Some dissidents run for the woods and hide, while others organize. In the case of the fugitive Knights Templar, the organization already existed. They possessed a rich tradition of secret operations that had been raised to the highest level through their association with the intricacies of Byzantine politics, the secret ritual of the Assassins, and the intrigues of the Moslem courts which they met alternately on the battlefield or at the conference table. The church, in its bloody rejection of protest and change, provided them with a river of recruits that flowed for centuries.

More than six hundred years have passed since the suppression of the Knights Templar, but their heritage lives on in the largest fraternal organization ever known. And so the story of those tortured crusading knights, of the savagery of the Peasants' Revolt, and of the lost secrets of Freemasonry becomes the story of the most successful secret society in the history of the world.

PART 1

THE

KNIG HTS

TEMPLAR

CHAPTER 1

THE URGE TO KILL

In 1347, over a thousand miles from London, the Kipchak Mongols were besieging a walled Genoese trading center on the Crimean coast. Kipchak besiegers were beginning to die in large numbers from a strange disease that appeared to be highly infectious. In what may be the world's first recorded instance of biological warfare, the Kipchaks began to catapult the diseased corpses over the walls.

A few months later, Genoese galleys from the besieged city put in at Messina in Sicily, with men dying at their oars and tales of dead men who had been thrown over the side all along the way. The sailors ignored the efforts of authorities to prevent their landing, and the Black Death set foot ashore in Europe. Carried by ships' rats, it moved onto the continent through the ports of Naples and Marseilles. From Italy it moved into Switzerland and Eastern Europe, meeting the spread through France into Germany. The plague came to England on ships landing at ports in Dorset and spread from there. Within two years it had killed off an estimated 35 to 40 percent of the population of Europe and Britain.

As in all times and places, famine, malnutrition, and the resultant lower immune defenses put out the welcome mat for the epidemic. A change in climate had produced longer winters and cooler, wetter summers, which had shortened and thwarted the growing season. From 1315 to 1318 torrential summer rains ruined crops, and mass starvation followed. Succeeding harvests

3

4 BORN IN BLOOD

were sporadic, but at least the people could survive. Then, in 1340, there was almost universal crop failure, and thousands perished in the worst famine of the century.

Even under what they would have considered ideal conditions, the general population was undernourished. Their diet was chiefly of wheat and rye, with few vegetables and a minimum of meat and milk‑‑partially because, even if they could afford them, there was no refrigeration or other means of preservation. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies in winter were a part of life. Hunting could provide fresh meat, but hunting rights belonged to the manor lords. A beating was a light punishment and death not uncommon for taking a deer, or even a rabbit, from the lord's forests. That so many took the risk speaks to the intensity of the biological craving for fresh food.

Disease generally finds its easiest victims among children, who do not develop a mature immune system until about the age of ten or eleven, and among the elderly, whose immune systems decline with advancing years, and so it was with the Black Death. Although people of all ages and all stations died in the tens of thousands, the very young and the very old dominate the statistics. It was the very opposite of a "baby boom," leaving few young people to enter the work force during the next generation.

The Black Death was not a single disease, but three, and the source of all three was a flea. A bacillus in the blood blocks the flea's stomach. As the flea rams its probe through the skin of its host, preferably the black rat, the bacillus erupts from the flea's stomach and enters the host, introducing the infection. As the rats died off, the fleas took to other animals and to humans.

In one form, the bacilli settle in the Iymph glands. Large swellings and carbuncles, called buboes, appear in the groin and armpits, which give this form of the disease the name "bubonic plague." The term "Black Death" comes from the fact that the victim's body is covered with black spots and his tongue turns black. Death usually comes within three days.

In another form – septicemic ‑ the blood is infected, and death may take a week or more. The fastest death comes from the most infectious form, the pneumonic, which causes an inflammation of the throat and lungs, spitting and vomiting of blood, a foul stench, and intense pain.

No scientific identification was made of the plague diseases at

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR S

the time, nor was anything known of the method of transmission. This permitted all manner of wild theories to be promulgated, of which the most common was that the Black Death was a punishment from God. Some even cursed God for the great calamity, and Philip VI of France took steps to prevent God from getting any angrier than He apparently already was. Special laws were passed against blasphemy, with very specific punishments. For the first offense, the lower lip of the blasphemer would be sliced off. For the second offense, the upper lip would go, and for the third offense the offender's tongue would be cut out.

Groups of penitents sprang up, publicly doing penance for sins that they could not specifically identify, but that were obviously serious enough to anger God to the point of destroying the human race. Only the most severe penance would do to expiate such horrible sin. Self‑flagellation turned into group flagellation as penitents walked the streets, often led by a priest, and beat one another with knotted ropes and whips tipped with metal to lacerate their flesh. Some carried heavy crosses or wore crowns of thorns.

Others found their own answers in uninhibited rites and sexual orgies. Some acted on the theory that since the world was ending shortly every possible pleasure should be indulged; others believed an appeal to Satan was the only alternative, now that they had been abandoned by God.

As always in the Middle Ages, some communities put the blame on the only non‑Christians in their midst, the Jews. Even though the Jews were dying from the Black Death themselves, they were accused of poisoning wells and causing the plague with secret rites and incantations intended to wipe out Christianity. Bloody pogroms were mounted in France, Austria, and especially‑‑as had been the case during the Crusades ‑ in Germany. In Strasbourg over two hundred Jews were burned alive. At one town on the Rhine the Jews were butchered, then their remains were sealed in wine barrels and sent bobbing down the river. The Jews at Esslingen who survived the first wave of persecution thought that their own world was coming to an end and gathered in their synagogue. They set the building on fire, burning themselves to death. Those Jews who weren't killed were frequently expelled, leaving their homes to spread their culture, and often the plague, to other areas. Poland saw its own persecutions

6 BORN IN BLOOD

in scattered areas, but that country was generally much safer than Germany, and German Jews streamed into Polish territory. This was the origin of the Ashkenazic (German) Jewish communities in Poland. They kept their German language, which gradually evolved into a vernacular called Yiddish.

Because of their crowded conditions and almost total lack of sanitation, the towns and cities were hardest hit at first, but as the townsmen dispersed to avoid the plague, they took it with them into the rural areas. As the farmers died off, fields went to weeds, and untended animals wandered the countryside until many of them died the same way their owners had. Henry Knighton, a canon of St. Mary's Abbey in Leicester, reported five thousand sheep dead and rotting in a single pasture. It has been estimated that the population of England when the plague first crossed the Channel was 4 million. By the time it subsided, the population had been reduced to less than 2.5 million.

News of the ravages of the plague in England reached the Scots, who concluded that this decimation of their ancient enemy could have come from no source other than an avenging God. They decided to assist the Almighty in His divine plan and attack the English in their weakened state. The call went out for the clans to gather at Selkirk Forest, but before they could begin their march south the plague struck the camp, killing an estimated five thousand Scots in a few days' time. There was nothing to do but abandon the invasion plan, so the still healthy, with the sick and dying, broke camp to return to their homes. Word of the gathering had reached the English, who moved north to intercept the invasion. They arrived in time to intercept and slaughter the dispersed Scottish army.

Incredibly, while the greatest death toll the world had ever known was in progress, the war between England and France kept right on going, each weakened side hoping that the other side was even weaker. Armies needed supplies, the products of craftsmen and farmers, of whom over a third had died. Armies needed money, and the population and products usually taxed for that purpose were declining. When the plague died out after a couple of years, the world was different than it had been before. It would never be the same again, because the lowest classes of society suddenly experienced a new power.

What had happened was that the one law that can never be bro

7

ken without consequences, the law of supply and demand, was in full force and effect-this time to the benefit of the farmer, the common laborer, and the craftsman. In the recollection of the landowning class, there never had been a time when farm labor or farm tenant supply did not exceed the demand for it. Now the foundations of a way of life that had worked for centuries were beginning to crack. In the dark ages of anarchy the individual had been helpless. The preservation of life itself was the major consideration, and men freely pledged themselves in servitude to a stronger man who would provide them with protection. These strong men pledged themselves to even stronger men, and the result was the feudal system. Men at all levels pledged military service, often for a specific campaign or a specific period, such as forty days a year. The warrior class became the nobility, and they required wealth for war-horses, weapons, and armor. They needed still more wealth, partially in the form of labor, to build fortified places where their followers could come for protection. These gradually grew from moated stockades and fortified houses to lofty stone structures requiring an army of stonecutters, masons, carpenters, and smiths. All this had to be paid for, and although some revenue might be generated by the loot of warfare or the ransom of wealthy captives, the primary source of that wealth was the land, and the labor of the people who worked it.

As the armored horseman came to dominate the field of battle, there came an "arms race" of knights. The pledge of a local baron to his count might now include his obligation to respond to a call to arms by bringing with him anywhere from a single mounted knight to dozens, depending upon the size of his holdings. A knight was expensive to equip and maintain. He needed at least one trained heavy war-horse, a lighter horse for ordinary travel, and more horses for his squire, servants, and baggage. He required personal armor, which was very expensive, as well as some armor for his horse. To support him in all this, in exchange for his services he was provided with land, and the people on that land.

The status of serfs had changed over the centuries. Some were gradually able to become tenant farmers, tilling farmland assigned to them on shares while still making payments to the manor lord in fixed terms of service in the manor fields. Customs varied from one manor to another, but generally the tenant farmer paid in

8 BORN Ir~ BLOOD

many ways for his tenure. On his death, his best farm animal went to the lord as a fee (the "heriot"), and his second‑best animal to the parish priest. Neither he nor any member of his family could marry without permission, which usually required a payment. In addition to his prescribed days of labor for the lord (often two or three days a week), he might be called upon to give extra service without pay, a requirement with the unlikely name of "love‑boon." He was subject to restrictions on gathering firewood, taking wood to repair his house, and even collecting the precious manure that would drop in the roads and byways.

If the manor lord owned a mill, the tenant had to use that mill and pay for the privilege. The same applied to manor ovens, frequently creating a monopoly on the baking of bread. In view of his rights and obligations, the tenant was not a serf, who was a man bound almost in slavery, but neither was he totally free. The greatest barrier to his liberty was the old law that took away his freedom of movement. These tenant farmers were required to stay on the manor to which they were attached by birth, where they lived in a cluster of houses called a "vill" (the obvious forerunner of "village"). For this reason the tenant was called a villein, pronounced almost the same way as the more disparaging term villain which was sometimes applied to him by his lord.

What most dramatically changed the status of many villeins was the manor lord's need for cash rather than a share of a crop that could not easily be transported to market for sale. There were almost no wagon roads, and grain crops could not be economically transported by packhorse, as was done with wool. The king needed cash to fight his French wars, and the nobles needed cash to pay mercenaries and to acquire transportation and supplies on the continent. Villeins began to make deals in which a ha'penny or penny might be given instead of a day's labor and a fixed cash payment in lieu of a share of crops. Their attitudes changed as they found themselves "renting" the land rather than trading their time and muscles for it. They felt free in the absence or reduction of the old customs of humbling servitude.

By the time of the Black Death, many of the English manors were held by the church. Some had been purchased, and many had been gifted. The extensive manorial holdings of the Knights Templar had been conveyed to the Knights of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem (the Hospitallers) after the Templars were sup

rHE KNIGHlS TEMrL~R g

pressed by Pope Clement V in 1312. All of the monastic orders had manorial properties with thousands of serfs and villeins attached to them. Even the substitution of cash for villein services often didn't meet the lord's or bishop's need for cash, and a prosperous tenant would be permitted to purchase his freedom for a lump sum. Unfortunately, such men usually did not foresee a need for documentation that would stand up in court and so recorded the manumission improperly, or not at all. The attitude of the church was simple: No manumission was valid unless it was a recorded part of a business transaction. Any other act of freeing a villein was treated as embezzlement of valuable church property.

Now the Black Death had taken away a third or more of the work force. With labor shortages, prices went up, especially for the products of a greatly reduced work force of craftsmen. There were far fewer bootmakers, weavers, carpenters, masons, and smiths. There was less money being generated, and it bought less in the face of rising prices.

This was a golden time for the previously oppressed villein. Manors were lying fallow and their owners needed the income. For the first time in his life the tenant farmer's services were in short supply and he could bargain for, and get, a better share of the harvest and generally better living and working conditions. For his spare‑time labor he could get double or triple the wages he was used to. Tenants began to leave their vills for better opportunities, much to the anger of their old landlords.

To put a stop to all this and restore things to comfortable normalcy, the English Parliament passed a Statute of Labourers in 1351. Primarily the statute tried to fix prices for labor at their preplague levels but it contained several extraordinary provisions. The rates for farm laborers were not just spelled out (two and a half pence for threshing a quarter of barley, five pence per acre for mowing, and so on), but, to enforce the rule, farm workers were to sllow themselves in market towns with their tools in their hands so that labor contracts would be made in public, not in secret. The statute forbade any extra incentives, such as meals. Farm contracts were to be made by the year and not by the day. Farm workers were to take an oath twice a year before the steward or constable of their vill, swearing that they would abide by the ordinances. They were forbidden to leave their own vills if

10 BORN IN BLOOD

work was available to them at home at the set prices. If any man refused to take the oath or violated the statute, he was to be put in the stocks for three days, or until he agreed to submit to the new law. For that purpose, the statute ordered that stocks be constructed in every single village in England.

Craftsmen were not overlooked. The statute set wages at three pence per‑day for a master carpenter, four pence for a master mason, three pence per day for roof tilers and thatchers. All producers of products ‑ saddlers, goldsmiths, tanners, tailors, bootmakers, and so on ‑ were to charge no more than their average price during the four years before the plague, and all were to take oaths that they would obey the law. Breaking the oath, and the law, carried an unusual punishment. For a first offense, the overcharger would be imprisoned for 40 days ‑ with the prison term to be doubled for each subsequent offense. Thus a third offense would mean prison for 160 days (40, 80, 160). Under this provision, if a bootmaker could be convicted on nine counts of selling shoes at too high a price, the ninth offense alone would earn him 10,240 days in jail.

Attempts were made to enforce the Statute of Labourers, some vigorous, but essentially it just didn't work. It was trying to suppress a popular black market filled with eager buyers and eager sellers. Actually, the situation got worse. As farm workers and craftsmen left the market place because of death or old age, a smaller pool of new young workers took their places because of the disproportionate rate of infant and child deaths during the Black Death. Inflation continued to climb. Villeins and serfs with no claim to freedom, or who were too closely watched to be able to move elsewhere, could only go about their daily tasks in ever-reduced circumstances because of higher prices for everything they bought. Just as much victims, because they had no bargaining power, were the lower orders of the clergy. The bishops, in order to maintain themselves in a proper state of luxury and to meet the demands of a papal court whose income had been shattered by a rival claimant to the Throne of Peter, refused to increase the stipends of their ordinary clergy. This left the village priests at near‑starvation levels in times of incessant inflation and gave them common ground with their parishioners against great lords, whether temporal or spiritual.

To add to the demand for goods and services, the Hundred

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR 11

Years' War had begun in 1337. This war saw the change from great mobs of people struggling in hand‑to‑hand combat, stabbing, cutting, and thrusting at each other, to the use of improved missiles ‑ means by which men could kill each other from a distance. Bows and arrows had been around forever, but were comparatively weak and no threat to the armor‑plated warrior, nor to his position as the invincible "tank" of the medieval battlefield. Before the improved missiles the most effective weapon on the field may not have been the knight, but rather his war‑horse. What today is thought of only as a heavy work‑horse was bred to carry a man and his weight of weapons and armor, as well as the weight of the horse's own armor and its massive horseshoes, which were terrible weapons in themselves. No mob of infantry could withstand that massive bulk crashing into it. For the melee following the charge, the war‑horse was trained to bite and kick.

Then along came the crossbow, presenting the first material threat to the battlefield superiority of the armored knight. Its short compound bow, made of layered wood, bone, and horn, could propel a short thick arrow (or "quarrel") at a speed that would penetrate light armor. Thus the armored warrior, the aristocrat in war or peace, could be killed by an opponent he could not get his hands on ‑ worse, an opponent from the lower classes. It wasn't fair, and if it wasn't fair to the lords, it probably was not in keeping with God's will. A pope went so far as to ban the use of the crossbow by Christians, but the ban had no noticeable effect. Bans on weapons never work because they are always accompanied by the unspoken caveat, "We won't use it unless we absolutely must in order to win."

The crossbow was not the ideal weapon, because it had two shortcomings. First, the range was short. More important, the crossbow was very difficult to draw. Some had a stirrup for the bowman's foot, to hold the bow to the ground, while the bowstring was attached to a hook, fastened to a strap around the bowman's waist or shoulders. He would crouch down, hook the string, and then use the entire strength of his legs and back to draw the bow to a locked position for firing. This procedure was not only slow but required strength. It required training to draw and to aim. In addition, the crossbow was relatively expensive to manufacture: A peasant subject to feudal military service would not have one lying about the house. The crossbowman became a mercenary.

12 BORN IN BLOOD

It took cash to employ the crossbowman's services, not feudal obligation. At the Battle of Crecy in 1346, the crossbowmen of the French army were a band of Genoese mercenaries. On the other side, the English were about to demonstrate a weapon that immediately overshadowed the crossbow, the so‑called English longbow ("so‑called" because it was actually the product of Welsh ingenuity). The demonstration, that day, of the superiority of the longbow rocked all of Europe. Forget the total death toll; the important item was that over fifteen hundred fully armored French dukes, counts, and knights had fallen in one battle. That single fact changed the course of European society. Previously, knights had expected to be killed, if at all, only by each other. They held the monopoly on warfare, and so on power. Now hundreds of invincible aristocrats had been done in by a handful of the lowest level of commoner with pieces of wood and string in their hands. It changed forever the way the two classes regarded each other. No longer was the feudal levy that called a mob of untrained peasants to war of any account. Archers became professional soldiers, well trained, well paid, and well treated. They became the heroes of the hour, and they were peasant heroes. It may be impossible for us to evaluate the class distinctions that had existed before that time. The armored knights were, to the peasant, invincible, and on such a lofty plane as to be superior creatures akin to gods from another planet. One did not even contemplate standing up to them, and now the gods had dropped a notch. The knight had reason to sit in his hall and stare at the fire with wrinkled brow, and the peasant had an entirely new feeling of his own worth and pride. He might still share that new worth with his fellows in whispers, but the thought once planted continued to grow.

With the changes in the conduct of war, the king more than ever needed feudal obligations to be fulfilled with money, rather than with service. The new professional soldier worked for pay and needed to be supplied with food, equipment, and baggage animals, as well as transportation to the continent. In spite of labor shortages, inflation, and disease, the monarchy would not relent in the pursuit of the Hundred Years' War, which had started in 1337. The only answer was‑‑quite literally‑‑taxes, taxes, and more taxes.

Out of that state of affairs grew a situation that had to cause

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR 13

Trouble. The landowners called upon old rights under the law, propounded by lawyers that only they could afford to hire, to take away a man's freedom and that of his descendants. Men who called themselves free were ordered to prove it. Genealogies and parish records were searched to prove that a man's mother or grandmother had been a villein or serf and that he had irrevocably inherited that status. It was the one way to use the law to get cheap and legally bound labor that could not leave for better conditions elsewhere. The only beneficiaries were the landowners. The bigger the landowner, the greater the benefit from the enforcement of villeinage, and the church was the biggest landowner of them all. It had the largest number of serfs and villeins to be held, or forced back from their temporary freedom elsewhere. Bitterness against the church grew among the common people, and the flames of their resentment were frequently fanned by the discontented lower clergy.

An Oxford priest and scholar named John Wycliffe set in motion more, perhaps, than he had intended when he began to preach church reform. He was especially incensed by the corruption of the church and by what he saw as its constant struggle for more power and material trappings, at the expense of the traditional pastoral mission of the church. He saw a direct line of contact between men and God that did not require the services of a priest. He claimed that no one but God had control over men's souls. He said that the king was answerable directly to God and did not need a papal intermediary. One of his most shocking claims, for its day, was that sacraments served by priests who were themselves sinners, and not in a state of grace, were of no effect whatever, and that included the pope. He even went so far as to translate the Vulgate Bible into English, on the grounds that all Christian men and women should have direct access to holy scripture, for in scripture he found perfection and would not question a word of it. However, he pointed out, there is no scriptural mention of a pope.

Such attacks on the church could not go unanswered, and Wycliffe was arraigned on charges of heresy at St. Paul's. That he was not sentenced to death is probably attributable to the London mob that raged in protest. Wycliffe was merely removed from his post and sent down to live in his parish of Lutterworth. He did not curtail his criticism of the church but redirected that criticism

14 BORN IN BLOOD

from the audience of his fellow churchmen to the people, who were of a mind to listen. His followers became wandering preaching priests and took Wycliffe's message to the towns and villages.

More immediately effective on the home front was John Ball, whom the French chronicler Jean Froissart called "a mad priest of Kent." Ball preached against class and privilege, including in the church. He also demanded agrarian reform, insisting that the landholdings of the great barons and of the church be taken away from them and distributed among the people. Since 1360 Ball and his following of priests had roamed central and southeastern England, preaching doctrines of equality of rights and the redistribution or common ownership of property. He was arrested by church authorities a number of times and finally excommunicated. In 1381, at the outbreak of the Peasants' Rebellion, he was in the archbishop's prison at Maidstone in Kent.

There had been hope that the French influence on the papacy would end when Pope Gregory XI returned the Holy See to Rome in 1377. Unfortunately, a large segment of the church hierarchy had not agreed with the move. By that time many of the cardinals were French and much preferred the French base at Avignon. When Gregory XI died the following year, the people of Rome rioted to secure their demand that the new pope be an Italian, and so he was, taking the name of Urban VI. The French cardinals declared the election invalid. They elected their own French pope, who would rule as Clement VII, and returned to Avignon. This was the Great Schism in the church, which was not healed for many years. It became a political schism as well, with the anti‑Roman Clement VII at Avignon supported by France, Scotland, Portugal, Spain, and several German principalities, while the Roman pope Urban VI was supported by the enemies of France: England, Hungary, Poland, and the German Holy Roman Emperor. Each pope excommunicated all of the adherents of his rival, barring them from the sacraments, so that all across Europe every single Christian soul of the time had been damned and placed outside God's protection by one pope or the other. This was not a circumstance to be taken lightly. In one instance pro‑English forces, supporters of the Roman pope, captured a French convent whose members recognized the pope at Avignon. The soldiers and their clerics had no problem agreeing that these poor misguided sisters were totally outside the protection

THE KNIGHTS TEMrLAR 15

of either civil or ecclesiastic law. Accordingly, they saw no deterrent to looting all of the possessions of the convent and raping all of the nuns. By the rules of the day, they didn't even have to mention the event at their next confessions.

And all the time, the war between England and France went on, with both sides starved for the tax revenues needed to support the conflict.

In 1377 a poll tax of fourpence per head had been imposed on all the people in England. In 1379 Parliament came up with a graduated tax based on social status. Both taxes failed, and some of the crown jewels had to be sold to maintain the war with France. In November 1380 the tax was set at one shilling per head, with the extraordinary provision that the rich should help the poor to pay the tax. They did not, of course, and the tax failed.

The English Parliament of 1376 became known to the people as the Good Parliament, primarily because it condemned corruption in the king's government. Addressing bribery, it said that the king's counselors should take nothing from any party to business brought before them except presents of little value, such as small items of food and drink. On the subject of taxation, the members asserted that if the king had loyal officers and good counselors he would be rich in treasure without any need for taxation, especially considering the "king's ransoms" exacted for the release of King David II of Scotland after his capture at the Battle of Neville's Cross in 1346 and for King John II of France, captured at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356. They suggested that the men who had bled away those fortunes should be accused and punished.

The Good Parliament also impeached a merchant of London named Richard Lyons, finding him guilty of various crimes of extortion and corruption. It was charged that, as a royal tax collector, he had generously helped himself to funds intended for the royal treasury. It was adjudged that all of his lands, goods, and chattels should be seized by the crown and that he should be imprisoned for life. Instead, Lyons's wealth and his friends secured a royal pardon for him.

The name "Good Parliament" may have been descriptive, but equally so would have been the title, "The Ignored Parliament."

So here we have an England in an incessant state of war, with skyrocketing inflation, attempts to return free men to bondage, a

16 BORN IN BLOOD

Great Schism in the church that found every man in England excommunicated by the Avignon pope, a growing segment of vocally angry priests, and the burden of the highest poll tax ever levied upon the people. The powder keg was filled to the brim. In the spring of 1381, the government accelerated its efforts to collect the tax and the fuse was lit. The explosion of rebellion was just a few days away.

cHArTER 2

"FOR NOW IS TYME

TO BE WAR"

The Encyclopedia Britannica calls it a "curiously spontaneous" rebellion.

Barbara Tuchman, in her fourteenth‑century history, A Distant Mirror, said that the rebellion spread "with some evidence of planning."

Winston Churchill went further. In The Birth of Britain he wrote, "Throughout the summer of 1381 there was a general ferment. Beneath it all lay organization. Agents moved round the villages of central England, in touch with a 'Great Society' which was said to meet in London."

The spark of rebellion was being fanned vigorously, and finally the signal was given. Even though he had been arrested, excommunicated, and even now was a prisoner in the ecclesiastic prison at Maidstone, in Kent, letters went out from priest John Ball and from other priests who followed him. Clerics were then the only literate class, so letters must have been received by local priests and were obviously intended to be shared with or read aloud to others. They all contained a signal to act now, which could put to rest the concept that the rebellion was simply a spontaneous convulsion of frustration that just happened to affect a hundred thousand Englishmen at the same time. This from a letter from John Ball: "John Balle gretyth yow wele alle and doth yowe to

1 7

18 BORN IN BLOOD

understande, he hath rungen youre belle. Nowe ryght and myght, wylle and skylle. God spede every ydele [ideal]. Now is tyme." From priest Jakke Carter: "You have gret nede to take God with yowe in alle your dedes. For now is tyme to be war.'~ From priest Jakke Trewman: "Jakke Trewman doth you to understande that falsnes and gyle have reigned too long, and trewthe hat bene sette under a lokke, and falsnes regneth in everylk flokke.... God do bote, for now is tyme."

One letter from John Ball, "Saint Mary Priest," is worth quoting in its entirety. Even with the medieval English spelling, the meaning will be clear. Lechery and gluttony were frequent points in his accusations of high church leaders. "John Balle seynte Marye prist gretes wele alle maner men byddes hem in the name of the Trinite, Fadur, and Sone and Holy Gost stonde manlyche togedyr in trewthe, and helpez trewthe, and trewthe schal helpe yowe. Now regneth pride in pris [prize] and covetys is hold wys, and leccherye withouten shame and glotonye withouten blame. Envye regnith with tresone, and slouthe is take in grete sesone. God do bote, for nowe is tyme amen."

In all the letters quoted, the emphasis has been added to identify the common signal "now is tyme." More evidence of planning and organization would come.

The violence erupted in Essex, prompted by new and more stringent efforts to collect a third poll tax. The idea of having special commissioners to enforce the tax collection had come from the king's sergeant‑at‑arms, a Franciscan friar named John Legge. That idea would cost him his head a few weeks later.

The commissioners in some instances attacked their duties overzealously. Some were reported to have examined young girls to see if they had engaged in sexual intercourse, as an aid to determining whether or not they were fifteen years of age and so taxable. One man, John of Deptford, was arrested after he struck the tax gatherer who had raised his daughter's dress to see if she had pubic hair, evidence of taxable age.

In some areas the tax collectors were either simply ignored or beaten up by the villagers. A great local lord, John de Bamptoun, set himself up in the town of Brentwood in Essex and demanded that the men of the neighboring towns come to him with complete lists of names and their tax money. Over a hundred men responded to his orders‑‑not to pay the taxes, but to inform him

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR 19

that they had no intention of doing so. Optimistically, de Bamptoun ordered his two sergeants‑at‑arms to arrest the hundred villagers and put them in prison. The crowd angrily attacked the royal officers, and de Bamptoun counted himself lucky to be allowed to flee back to London.

In response, the government sent back Sir Robert Bealknap, chief justice of common pleas. Sir Robert came armed with specific indictments and statements signed by jurors. (In those days, jurors were the opposite of independent. They were witnesses, literally those with "wit‑ness" or "possession of knowledge" of the matter at hand, and frequently they were the accusers as well). In spite of Bealknap's ponderous authority, his reception was no better than that previously accorded de Bamptoun. The locals seized the royal party and forced Bealknap to reveal the names of the jurors who had named and sworn against de Bamptoun's assailants. With that information, parties set out to hunt them down. Jurors caught were beheaded and their heads mounted on poles, as examples to others, while those who couldn't be found had their houses burned or pulled down. As for the chief justice, he was berated as a traitor to the king and to the kingdom but in the end was permitted to return to London. Not allowed to go with him were his three clerks, who were recognized as the same clerks who had been with de Bamptoun. They were beheaded.

Meanwhile, in Kent, the county just south of Essex across the Thames, a knight of the king's household, Sir Simon Burley, had come to Gravesend and had leveled against a freeman named Robert Belling the charge that Belling was Burley's serf. He set a fine of three hundred pounds in silver as the price of Belling's liberty. The men of Gravesend were outraged at both the charge and the fine, a sum they declared would ruin Belling entirely. The royal officer responded by having Belling bound and thrown into the dungeon at nearby Rochester Castle. At the same time, a tax commission had arrived in Kent on a mission similar to that of Sir Robert Bealknap in Essex; the Franciscan sergeant‑at‑arms John Legge came armed with specific indictments against a number of people in the county. They had planned to establish the seat of the Kentish inquiry at Canterbury, but were driven off by the local citizenry.

As word of these events spread, the men of Kent began to gather, centered on the town of Dartford. A group of Essex men

20 BORN IN BLOOD

crossed the Thames in boats to join them. Showing not just organization but perhaps discipline as well, the leaders decreed that no men who lived within twelve leagues (about thirty‑six miles) of the sea would be allowed to join their march, because those men might be needed at home to help fight off any surprise French attack on the English coast.

The Kentish mob moved not toward London but away from it, heading east to lay siege to Rochester Castle, where they demanded the release of Robert Belling. After just half a day, and no recorded defense, the constable of the castle opened the gates to the rebels. They released Belling and every other prisoner, then turned south to Maidstone, where they arrived on June 7. There they were joined by more men, including one known as Walter the Tyler. Remarkably, he was immediately acknowledged by thousands of men as their supreme commander and gave his name to the rising: "Wat Tyler's Revolt." Nothing is known of Wat Tyler's prior life, nor of the means by which a supposedly disorganized mob acknowledged his leadership on the very day he arrived.

One of Tyler's first acts was to free John Ball, the "Saint Mary Priest" of York, from the church prison at Maidstone, and Ball became the unofficial chaplain of the expedition from that point forward.

Still moving away from London, Tyler took his force farther east to Canterbury, the seat of the leading churchman in England. That Tyler planned all along for his rude army to march on London is indicated by the rebels' first act upon their arrival at Canterbury on Monday, June 10. Thousands of rebels crowded into the church during high mass. After kneeling, they shouted to the monks to elect one of their number to be the new archbishop of Canterbury, because the present archbishop (who was off in London with the king, who had recently appointed him chancellor of the realm) "is a traitor and will be beheaded for his iniquity," as indeed he was before the week was over. The rebel leaders then asked for the names of any "traitors" in the town. Three names were provided, and the three men were sought out and beheaded. Then the rebels left the town, allowing just five hundred Canterbury men to join them because Canterbury was near to the coast and the balance of the men would be needed in the event of an attack by the French.

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR 21

On the same day (June 10) that Tyler took over Canterbury in Kent, the gathering Essex mob sacked and burned a major commandery of the Knights Hospitallers called Cressing Temple. This wealthy manor had been given to the Knights Templar in 1 l 38 by Matilda, the wife of King Stephen. When the Templars were suppressed by Pope Clement V, all of their property in Britain, including this manor of Cressing, was given to the Hospitallers. The church owned one‑third of the land surface of England at that time and suffered greatly at the hands of the rebels, but no single group suffered losses comparable to those inflicted over the next few days on the Knights Hospitallers, who seemed to be on an especially aggressive hit list of the rebel leaders.

The following day, June 11, the rebels in both Essex and Kent turned toward London. Even with the burning, beheading, and destruction of records along the way, their purpose and discipline were such that both groups, upwards of a hundred thousand men, made the seventy‑mile journey in two days, reaching the city at almost the same time.

Warned of the rebels' approach, the fourteen‑year‑old King Richard II moved from Windsor to the Tower of London, the strongest fortress in the kingdom. He was joined there by an entourage that included Sir Simon Sudbury, who was both archbishop of Canterbury and chancellor; Sir Robert Hales, who was both the king's treasurer and the prior of the order of the Knights of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem (the Hospitallers); Henry Bolingbroke, who would one day depose Richard and take the throne himself as Henry IV; the earls of Oxford, Kent, Arundel, Warwick, Suffolk, and Salisbury; and other peers and lesser officials, including the chief justice Sir Robert Bealknap, the unsuccessful tax collector John de Bamptoun, and the hated Franciscan sergeant‑at‑arms, John Legge. They all had reason to fear for their lives at the hands of the rebel horde advancing on the city.

On June 12 the Essex men began arriving at Mile End, near Aldgate. Across the river, the Kentish rebels gathered at Southwark, at the south end of London Bridge. Confederates and sympathizers streamed out of London to join them. One Kentish group came through nearby Lambeth, on the south side of the Thames, and sacked the archbishop's palace there, burning the furnishings and all the records they could find. (On that same day, across the river in the Tower, from where he could see the smoke

ZZ BORN IN BLOOD

rising from his palace, the archbishop returned the Great Seal to the king and asked to be relieved of his public duties as chancellor.) Other rebel groups broke open the prisons on the south side of the river, including the ecclesiastic prison of the bishops of Winchester on Clink Street, a location that gave the name "the clink" to prisons everywhere. On smashing open the Marshalsea prison in Southwark, the mob searched for its commander, Richard Imworth, famous for his cruelty. Unable to locate Imworth, they contented themselves, for the moment, with the destruction of his house.

Messengers went out to the rebels from the king, asking the reason for this disturbance of the peace of the land. The answer came back that the uprising was dedicated to saving the king and to destroying traitors to king and country. The king's reply to this was to ask the rebels to cease their depredations and wait until he could meet with them to resolve all injustices against them. The rebels agreed and asked the king to meet with them early in the morning of June 13 at Blackheath on the Thames, a few miles from London. The men of Kent gathered at the meeting place on the south bank of the river and the men of Essex on the north. The king and his party left the Tower in four barges but only got as far as the royal manor at Rotherhithe, near Greenwich, where Archbishop Sudbury and Sir Robert Hales persuaded the party to get no closer to the rebels. Upon learning that the king was not coming to them as promised, the Kentish leaders sent the king a petition asking him for the heads of fifteen men. Their list included the archbishop of Canterbury, the prior of the Hospitallers, Chief Justice Bealknap, and the tax collectors John Legge and John de Bamptoun. Not surprisingly, the royal council would not agree to these demands, and the barges returned to the Tower. Each on their own side of the river, the Essex men moved toward Aldgate and the Kentish faction marched back toward Southwark and London Bridge. For reasons we shall probably never know, Aldgate was undefended, and the Essex rebels simply walked into the city. As much mystery attaches to the approach of the Kentish mob to London Bridge. No attempt was made to man the fortified gatehouse, and the drawbridge was lowered for them to cross.

Moving through the city, the rebels touched nothing until they reached Fleet Street. There they attacked the Fleet prison and

THE KNIGHTS TEMPLAR 23

released all the inmates. They destroyed two forges that the Hospitallers had taken over from the Templars. Some joined a London mob and went to the Savoy Palace of the hated royal uncle, John of Gaunt, pausing on the way only to destroy any houses they could identify as belonging to the Hospitallers. The Savoy Palace itself was destroyed in a mood of rage. Furniture and art objects were smashed, linens and tapestries were burned. Jewels were hammered to powder. Finally the building was set aflame, boosted by the addition of several kegs of gunpowder.

From the Savoy the rebels returned to the Hospitaller property between Fleet Street and the Thames, to buildings leased by that order to lawyers who practiced before the king's court in the adjoining royal city of Westminster. They vandalized and burnt the lawyers' buildings, burnt their records, and killed anyone who registered an objection. They destroyed the other Hospitaller buildings on the property, with one exception. Instead of burning the rolls and records stored in the church where they found them, they went to the trouble of carrying them out into the high road for burning, avoiding any damage to the church itself. One historian goes so far as to say that certain of the mob "protected" the church from damage. This attitude was an anomaly in the midst of an orgy of destruction of church property and church leaders. This property, too, had been taken from the Templars and given to the Hospitallers, and even today that portion of the City of London is known simply as "The Temple." The church that was left unscathed by the rebels had been the principal church of the Knights Templar in England. This attitude toward the old Templar church stands out in marked contrast to the mob's feeling for the grand priory of the Hospitallers at Clerkenwell, where they turned next. Still seeking out Hospitaller property for destruction along the way, they arrived at Clerkenwell and embarked upon an effort of total destruction. While the Templar church still stands today, all that remains of the principal Hospitaller church at Clerkenwell is the underground crypt.

Some of the mob went from London into the City of Westminster, where they released all of the prisoners in Westminster prison. Moving back into London, they did the same at the famous Newgate prison, taking chains and shackles to place on the altar of a nearby church.

One group went to the Tower to seek an audience with the

24 BORN IN BLOOD

king. When they were unsuccessful, they laid siege to the Tower. Word was sent out by the rebel leaders to the bands still roving the city that every member of the Chancery and Exchequer, every lawyer, and anyone who could write a writ or letter should be beheaded. Ink‑stained fingers were enough to condemn a man to death on the spot. The church at that time had a virtual monopoly on literacy, so the victims were most likely to be administrative clerics, who also held a near monopoly on what we might now think of as the "civil service" of the king's government.

So far, the king's council had appeared numbed into inactivity, but something had to be done, and finally a plan was agreed upon. It could not be based on force, because they had no force. The weapons they did have were trickery and deceit. Word was cried out in every ward of the City that on the following morning of Friday, June 14, the king and his council would meet with the rebels and that all of their demands would be satisfied. The promise was easily made because there was no intention to keep it. The place selected was the open fields at Mile End, outside the City beyond the Aldgate. It was expected that this move would achieve the initial goal of pulling the rebels out of the City. In fact, most of them did go, but Wat Tyler and his chief lieutenant, Jack Strawe, stayed behind with several hundred men. Their "chaplain," the priest John Ball, stayed with them. The rebel leadership had something more important to do than meet with the king to discuss manumission of villeinage and serfdom.

In those days, the Thames came right up to and inside the south wall of the Tower, so there was direct access by means of a water gate. As the king's party made ready to go to Mile End on Friday morning, the archbishop of Canterbury tried to escape by boat. He was recognized, and the ensuing hue and cry caused his crew to beat its way back through the water gate to the safety of the Tower.

As promised, the king's party left the Tower to meet the rebels at Mile End. Chroniclers tell us that he was accompanied by such dignitaries as the earls of Kent, Warwick, and Oxford, as well as by the mayor of London and "many knights and squires." What they do not tell us is why he was not accompanied by two of his very highest officials, Sir Simon Sudbury, who was the archbishop of Canterbury and chancellor of the realm, and Sir Robert Hales, who was prior of the order of the Knights Hospitaller and

THE KNIGHTS TEMrLAR 2 5

the king's treasurer. We shall never know whether they chose to stay behind or were ordered to do so. There is also no record of who spoke for the rebels at Mile End while Tyler, Strawe, and Ball were on a mission more important to them back in London.

At the meeting place all seemed to go well. The rebels asked two things: first, that they should have the right to hunt down and execute all traitors to the king and common people, and second, that no man should be bound to another in serfdom or villeinage. Every Englishman should be a free man. As to the first request, the king agreed that all "traitors" should be put to death, provided that thev were proven guilty under the law. He asked that all such accused be brought to him for trial. As to the request for universal freedom, he had brought about thirty clerks with him, who began speedily grinding out writs of manumission.

As soon as the king was safely out of the City, Tyler, Strawe, and Ball made their move. Incredibly, their plan was to take the Tower of London with a few hundred ill‑armed men. The Tower had been built to be the most secure fortress in Britain, so secure that it housed the royal mint. It was equipped with a heavy gate, an iron portcullis, and a drawbridge. At the time of Tyler's approach, the Tower was manned by professional soldiers, including hundreds of experienced archers. It had leadership and authority in the person of Archbishop Sudbury and, even more so, in the person of Sir Robert Hales, commander of a military order.

Here again, there had to have been collusion and friends on the inside. Tyler and his small band found the drawbridge down, the portcullis up, the gate open. They simply walked into the Tower. No contemporary chronicler refers to so much as a scuMe.