Brunelleschi's Dome

By Wor. Bro. Frederic L. Milliken

I had completely forgotten this gem of a video I had in my collection. It was just sitting there idly until I attended the Festive Board of Lodge Veritas in Oklahoma, where Masonic artist Ryan Flynn was the guest speaker. Flynn, who had studied for a year in Florence, mentioned Brunelleschi’s Dome in his presentation. In fact, Flynn was to comment that the Dark Ages were not so dark in some quarters of Europe, especially Florence.

If you are a Freemason you will find an instant affinity with the art of building, especially a work of art. I warn you that the video is long, but one you cannot stop once you start. It is that riveting. So find yourself an uninterruptable hour and bring the pop and the popcorn before getting started.

Here are snippets from an article Tom Mueller wrote for the National Geographic:

Brunelleschi's dome. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

In 1418 the town fathers of Florence finally addressed a monumental problem they’d been ignoring for decades: the enormous hole in the roof of their cathedral. Season after season, the winter rains and summer sun had streamed in over Santa Maria del Fiore’s high altar—or where the high altar should have been. Their predecessors had begun the church in 1296 to showcase the status of Florence as one of Europe’s economic and cultural capitals, grown rich on high finance and the wool and silk trades. It was later decided that the structure’s crowning glory would be the largest cupola on Earth, ensuring the church would be “more useful and beautiful, more powerful and honorable” than any other ever built, as the grandees of Florence decreed.

Still, many decades later, no one seemed to have a viable idea of how to build a dome nearly 150 feet across, especially as it would have to start 180 feet above the ground, atop the existing walls. Other questions plagued the cathedral overseers. Their building plans eschewed the flying buttresses and pointed arches of the traditional Gothic style then favored by rival northern cities like Milan, Florence’s archenemy. Yet these were the only architectural solutions known to work in such a vast structure. Could a dome weighing tens of thousands of tons stay up without them? Was there enough timber in Tuscany for the scaffolding and templates that would be needed to shape the dome’s masonry? And could a dome be built at all on the octagonal floor plan dictated by the existing walls—eight pie-shaped wedges—without collapsing inward as the masonry arced toward the apex? No one knew.

The first problem to be solved was purely technical: No known lifting mechanisms were capable of raising and maneuvering the enormously heavy materials he had to work with, including sandstone beams, so far off the ground. Here Brunelleschi the clockmaker and tinkerer outdid himself. He invented a three-speed hoist with an intricate system of gears, pulleys, screws, and driveshafts, powered by a single yoke of oxen turning a wooden tiller. It used a special rope 600 feet long and weighing over a thousand pounds—custom-made by shipwrights in Pisa—and featured a groundbreaking clutch system that could reverse direction without having to turn the oxen around. Later Brunelleschi made other innovative lifting machines, including the castello, a 65-foot-tall crane with a series of counterweights and hand screws to move loads laterally once they’d been raised to the right height. Brunelleschi’s lifts were so far ahead of their time that they weren’t rivaled until the industrial revolution, though they did fascinate generations of artists and inventors, including a certain Leonardo from the nearby Tuscan town of Vinci, whose sketchbooks tell us how they were made.

Having assembled the necessary tool kit, Brunelleschi turned his full attention to the dome itself, which he shaped with a series of stunning technical

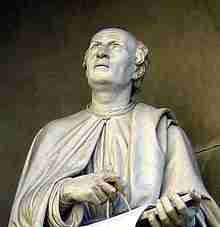

Statue of Filippo Brunelleschi near the Duomo Santa Maria del Fiore,

looking up at the dome (inset) (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

innovations. His double-shell design yielded a structure that was far lighter and loftier than a solid dome of such size would have been. He wove regular courses of herringbone brickwork, little known before his time, into the texture of the cupola, giving the entire structure additional solidity.

On March 25, 1436, the Feast of the Annunciation, Pope Eugenius IV and an assembly of cardinals and bishops consecrated the finished cathedral, to the tolling of bells and cheering of proud Florentines. A decade later another illustrious group laid the cornerstone of the lantern, the decorative marble structure that Brunelleschi designed to crown his masterpiece.

Mueller writes in another National Geographic piece:

Brunelleschi's Dome

To this day, we don't know where he got the inspiration for the double-shell dome, the herringbone brickwork, and the other features that architects through ensuing centuries could only marvel at. (Explore the hidden details of Brunelleschi's daring design.)

Perhaps the most haunting mystery is the simplest of all: How did Brunelleschi and his masons position each brick, stone beam, and other structural element with such precision inside the vastly complex cathedral—a task that modern architects with their laser levels, GPS positioning devices, and CAD software would still find challenging today?

For 40 years, Ricci has tried to answer these questions in the same way that Brunelleschi did: by trial and error. He has built scale models of Brunelleschi's innovative cranes, hoists, and transport ships. He has scoured the interior and exterior of the dome for clues, mapping each iron fitting and unexplained stub of masonry and cross-referencing them against the archival documents concerning the dome's construction.

And since 1989, in a park on the south bank of the Arno River half a mile downstream from Santa Maria del Fiore, he has been building a scale model of the dome that's 33 feet (10 meters) across at its base and consists of about 500,000 bricks.

"Theoretical models are fine for grasping the dome's geometry," Ricci says, "but of limited use in understanding the problems Brunelleschi dealt with while building the dome. And that's what really matters to me: how Brunelleschi put bricks together."

In the process of putting together half a million bricks, Ricci may have solved one of Brunelleschi's biggest secrets: how a web of fixed and mobile chains was used to position each brick, beam, and block so that the eight sides of the dome would arc toward the center at the same angle.

Inspired by documentary references to "the star of the cupola," Ricci started by suspending a star-shaped hub in the center of his model dome. From the eight points of this star he stretched eight chains radiating outwards and downwards to the walls of his model, attached to hooks in the walls, in the corners of the octagonal plan (similar hooks are present in the dome itself).

Next he linked these eight chains with horizontal ropes, which traced arcs along the eight sides of the octagon where the walls were rising. Seen from above, these ropes resemble the petals of a flower.

After last year's memorial procession ended, Ricci laid out for me some of the evidence for his theory of the dome's flower, which he considers to be the breakthrough in his conception of Brunelleschi's method. "In fact, Santa Maria del Fiore means Saint Mary of the Flower," Ricci notes. "And the symbol of Florence is a flower, the lily."