Note: This material was scanned into text files for the sole purpose of convenient electronic research. This material is NOT intended as a reproduction of the original volumes. However close the material is to becoming a reproduced work, it should ONLY be regarded as a textual reference. Scanned at Phoenixmasonry by Ralph W. Omholt, PM in June 2007.

THE FREEMASON AT WORK

BY HARRY CARR

With All Good Wishes

THE FREEMASON AT WORK

BY

HARRY CARR

Past Junior Grand Deacon

P.M., (Secretary and Editor 1961 - 1973) of the

Quatuor Coronati Lodge, No. 2076, London

P.M., 2265, 2429, 6226, 7464

Honorary Member of 236, 2429, 2911, 3931, 7998, 8227

Fellow of the American Lodge of Research, N.Y., Honorary Member of

Ohio Lodge of Research, Masonic Research Lodge of Connecticut,

Loge Villard d'Honnecourt, No. 81 Paris (France),

Mizpah Lodge, Cambridge, Mass., Arts and Crafts Lodge, No. 1017, Illinois,

Walter F. Meier Lodge of Research, No. 281, Seattle, Washington,

Research Lodge of Oregon, No. 198, Portland,

Victoria Lodge of Education and Research, Victoria, B.C.

Honorary P.A.G.D.C. Grand Lodge of Iran

LONDON

LEWIS MASONIC

© Harry Carr 1976

First Published in Great Britain in 1976

Sixth and revised edition 1981

Reprinted 1983

Published by

A Lewis (Masonic Publishers) Ltd Terminal House, Shepperton, Surrey

who are members of the Ian Allan Group, and printed

by Ian Allan Printing Ltd at their works at

Coomblelands in Runnymede, England

ISBN 0 85318 126 8

Carr, Harry The Freemason at Work - 6th revised edition

1. Freemasons

I. Title

366'.l HS395

FOREWORD

By R.W.Bro. Sir Lionel Brett, P.Dist.G.M., Nigeria

THOSE who hold that good wine needs no bush may feel that a Foreword to this book is superfluous. There is some force in this view for the generation of readers who have known Bro. Harry Carr in person or by reputation, and grown accustomed to a regular flow of articles under his name, but Masonic books have a way of surviving in lodge book‑shelves long after they have gone out of print, and it seems certain that this one will be read, quoted and discussed by generations who have not had those advantages. A Foreword will justify itself if it helps future generations to put Bro. Carr in his proper class as a trustworthy guide, and this Foreword may be regarded as addressed to them.

The United Grand Lodge of England makes little provision for organized Masonic instruction. Every member receives a copy of the Book of Constitutions, but apart from the annual Prestonian Lectures the rest is left to the efforts of lodges or individuals. The novice with an inquiring mind will not be content for long with a printed ritual and will demand further information, whether on the practice in lodge, or on the form of the after‑proceedings, or on some aspect of the history of operative or speculative Freemasonry. If he consults an individual, he will be fortunate to find a Preceptor or other informant as well equipped all round as Bro. Carr. If he turns to a book, there are a number in print which he can profitably study, but he may not always know where to look for an answer to his particular question. The distinguishing feature of this book is that it deals with questions that were actually exercising brethren over a period of twelve years.

Bro. Carr describes the genesis of the book in his Introduction. It was largely thanks to him that the material it contains came to be included in the Summonses and Transactions of a lodge formed by and for erudite scholars, and the variety of his Masonic experience made him exceptionally well qualified to provide the material. As Deputy Preceptor and later Preceptor of a Lodge of Instruction for many years he was in close touch with the needs of brethren at the start of their Masonic careers. As a member of the Board of General Purposes of

vii

viii FOREWORD

Grand Lodge he had direct experience of the administration of the affairs of the governing body of English Freemasonry. He first showed his interest in Masonic research in 1936, and his election to full member‑ship of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge in 1953 is proof of the standing he already enjoyed as a Masonic scholar.

Over the years Bro. Carr has made many contributions to Masonic literature, both as author and editor. During the period when he was Secretary of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge and Editor of its Transactions his publications in AQC included full‑scale papers presented to the Lodge and articles of varying length in Miscellanea Latomorum and `Papers and Essays' as well as answers to Queries. They all display the same pattern: facts first; conclusions, if any, later; and no concessions to those who prefer myth to history.

The queries Bro. Carr was asked to deal with vary greatly in complexity as well as in subject‑matter. Where a pure issue of fact is concerned the answer may be accepted as authoritative. Where someone has put the insoluble question, why a particular expression is used in the ceremonies, Bro. Carr's historical exposition provides as satisfactory an answer as the case admits; he might have cited what Justice Holmes said in an analogous case - 'The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience.' Where the question involves expressing a preference between two or more possible solutions, Bro. Carr has not been afraid to follow a statement of the relevant facts with an expression of his own opinion, but he has not done so dogmatically, or claimed to have said the last word. Bro. Carr's opinion on any Masonic question must carry weight, but he would certainly not wish anyone to adopt it merely on the authority of his name, and the most important thing is that he provides material for informed discussion.

The reader a hundred years hence may confidently take it that on the matters it deals with this book accurately shows the state of Masonic knowledge, and the opinions that an unusually well informed Free‑mason could reasonably hold, at the time of its publication, and it is a great privilege to be associated with the book, if only in the ancillary capacity of writer of the Foreword.

LIONEL BRETT

CONTENTS

Page

FOREWORD by R.W.Bro. Sir Lionel Brett, P.Dist.G.M. Nigeria vii

List of Illustrations and Diagrams xv

List of Abbreviations xvi

INTRODUCTION xvii

INDEX 404

QUESTIONS:

1. The Quatuor Coronati 1

2. The Bright Morning Star 2

3. The Compasses and the Grand Master 3

4. It proves a slip 6

5. Why two Words for the M.M.? 8

6. Apprentice and Entered Apprentice 10

7. Titles of the United Grand Lodge of England 11

8. Every Brother has had his due 12

9. Arms of the Grand Lodge. London Masons' Company.

The first Grand Lodge, 1717-1813. Antients' Grand

Lodge, 1751-1813. The United Grand Lodge 14

10. L.F. across the Lodge 19

11. Raising and lowering the Wardens' Columns 21

12. Orientation of the Bible and of the Square and Compasses 23

13. The Points of Fellowship 27

14. The second part of the `Threefold Sign' 30

15. Divided loyalties? The Sovereign; place of residence;

native land 33

16. Squaring the lodge 35

17. The Winding Stairs 36

18. Penalties in the Obligations 38

19. Confirming minutes and voting; the manner observed

among Masons 45

20. The St. John's Card 46

For particular subjects please use the Index

ix

x CONTENTS

Page

21. Masonic ritual in England and U.S.A. 47

22. The Bible in Masonic literature and in the lodge. When

did lodges take on a formal setting? 51

23. Duly constituted, regularly assembled and properly dedi-

cated 54

24. The Secretary's annual subscription 56

25. What is the age of the Third Degree? 58

26. Dues Cards; Grand Lodge Certificates; Clearance Certi-

ficates 62

27. Architecture in Masonry 64

28. Questions after raising 66

29. Public Grand Honours 72

30. Breast, hand, and badge 73

31. Gauntlets 75

32. Lewis; Lewises and the `Tenue-Blanche' 77

33. Darkness visible 78

34. The points of my entrance 79

35. Cowans; cowans and intruders 86

36. Declaring all offices vacant 89

37. Replacement of deceased officers 90

38. Deacons as `Floor-officers' 91

39. Three steps and the first regular step 93

40. St. Barbara as a Patron Saint of the Masons 96

41. Sponsoring a new lodge 97

42. The Beehive 100

43. Fellowcrafts and the `Middle Chamber' 103

44. The Master's hat 106

45. On Masonic visiting 108

46. Visiting of lodges by `unattached' Brethren 110

47. The network over the Pillars 111

48. Will you be off or from? 113

49. London Grand Rank 115

50. Rosettes 116

51. The knob or button on a P.M.'s Collar 116

52. The Ladder and its symbols in the first Tracing Board 117

53. Symbolism and removal of gloves 120

54. The Risings; their purpose; modern practice 121

55. Emulation Working 123

For particular subjects please use the Index

CONTENTS xi

Page

56. Masonic Fire: Craft Fire; silent Fire 124

57. Holiness to the Lord 127

58. Wearing two Collars 129

59. Improper solicitation 129

60. Bible openings 134

61. The Lion's Paw or Eagle's Claw 136

62. A modernized ritual? 137

63. The left-hand Pillar 138

64. The valley of Jehoshaphat 139

65. Aprons; flap up, corner up 140

66. Signs given seated 143

67. What do we put on the V.S.L? 144

68. Three, five and seven years old 146

69. Origin of the word `Skirret'. Why is it not depicted the

Grand Lodge Certificate? 147

70. The Queen and the Craft 150

71. Calling off; in which Degree? 150

72. Sir Winston Spencer Churchill 151

73. William Preston and the Prestonian Lectures 152

74. The Hiramic legend as a drama. Illogicalities in the Third

Degree 154

75. Orientation of the letter G 157

76. Passwords 158

77. With gratitude to our Master ... 162

78. The origin of the Collar 163

79. The Working Tools 164

80. Tubal Cain 169

81. Crossing the feet 171

82. The Master's Light 173

83. Masonic After-proceedings; Table & Toasting practices

in the London area. Seating. Receiving the W.M.

Grace. The Gavel. Taking Wine. The Toast List and

`Fire' 174

84. Sepulchre or sepulture? 184

85. The W.M.'s Sign during Obligations 186

86. Deacons as messengers 187

87. The exposures. How can we accept such evidence? The French exposures 189

For particular subjects please use the Index

xii CONTENTS

Page

88. Titles during initiation 198

89. Crossing the wands 199

90. Opening and closing in the Name of the GAOTU 202

91. The opening and closing odes 204

92. Topping-out ceremonies 205

93. This `Glimmering Ray' 206

94. The Loyal Toast 207

95. The altar of incense; a double cube 207

96. Lettering and halving 208

97. The Light of a Master Mason 209

98. Masonic and Biblical dates and chronology 211

99. Who invented B.C., and A.D.? 212

100. Due examination of visitors 212

101. The name `Hiram Abif' 213

102. `Time Immemorial' lodges 215

103. The Great Lights and the Lesser Lights 217

104. The Lesser Lights, Sun, Moon and Master. Which is

which? 219

105. Instruction and improvement of Craftsmen; why only

Craftsmen? 222

106. So mote it be 224

107. Your respective columns; vouching within the lodge 225

108. The `half-letter' or `split-letter' system 226

109. Using the V.S.L. at Lodge of Instruction 227

110. The lodge on Holy Ground 228

111. The meaning of the word `Passing' 230

112. Unrecognized Grand Lodges 232

113. Pillars of brass or bronze? 233

114. The length of my cable-tow; a cable's length from the

shore 234

115. Compass or compasses 236

116. York Rite 237

117. Guttural, Pectoral, Manual, Pedestal 238

118. The 24-inch gauge and the decimal system: as a `working

tool' 239

119. Correct seating in lodge 241

120. The Charge to the Initiate 241

121. Monarchs themselves have been promoters of the art 244

For particular subjects please use the Index

CONTENTS xiii

Page

122. The point within a circle 247

123. The `Five Platonic Bodies' and the Royal Arch 248

124. Composition of the Board of General Purposes: Provincial

representation 251

125. Naming of lodges 253

126. Corn, Wine, Oil and Salt in the Consecration Ceremony 255

127. Progress in placing the Candidates. Turning the Candidate

in the Third Degree 257

128. Fidelity, Fidelity, Fidelity: the Sn. of Fidelity; the Sn. of

Reverence 257

129. Correct sequence of the Loyal Toast 261

130. Wardens' tests in the Second Degree and on the Winding

Stair 261

131. Landmarks: tenets and principles 263

132. Is symbolism a Landmark? 266

133. The consent and co-operation of the other two 267

134. Money and metallic substances 268

135. The attendance (signature) book 270

136. The Tyler's Toast 271

137. Globes on the Pillars: maps, celestial and terrestrial 272

138. The priest who assisted at the dedication of the Temple 275

139. Freemasonry and the Roman Catholic Church 277

140. Why Tylers? 282

141. When to produce the warrant 283

142. The evolution of the Installation ceremony and ritual 284

143. Salutations after Installation 308

144. The long Closing 310

145. The Square and Compasses and the Points 312

146. Masonic Toasts 313

147. Presentation of gloves 319

148. The chequered carpet and indented border 321

149. Tassels on the carpet 323

150. Hebrew inscriptions on Tracing Boards of the Third Degree 324

151. Hele, conceal . . . 326

152. The 47th proposition on the Past Master's Jewel 328

153. Ecclesiastes XII and the Third Degree 330

154. Opening a lodge: symbolism, if any 331

155. Symbolism of the Inner Guard 333

For particular subjects please use the Index

xiv CONTENTS

Page

156. Symbolism: interpretation and limitations 334

157. The Grand Pursuivant 336

158. The V.S.L. in our ceremonies 338

159. Orators in Freemasonry 339

160. Must all three chairs be occupied throughout the Craft

ceremonies? 342

161. Questions before Passing and Raising. Who may stay to

hear them? 342

162. Non-conforming candidates 343

163. U.S.A. lodges working in the Third Degree 345

164. The Wardens' columns; a pair or part of a set of three? 347

165. Admission of candidates in the Second Degree 348

166. The assistance of the Square 349

167. The Hailing Sign; when did it appear? 350

168. At, on, with, or in, the centre 351

169. Saluting the Grand Officers, and others 353

170. Position of the rough and smooth ashlars 353

171. The Immediate Past Master's Chair 356

172. The star-spangled canopy in Freemasonry 357

173. Do hereby and hereon . . . 359

174. The grave; its dimensions and location 359

175. Forty and two thousand 361

176. The Due Guard 362

177. Tests of merit and ability 366

178. Inaccuracies in the ritual 368

179. Why leave the East and go to the West? 370

180. Ravenous or ravening? 372

181. The earliest records of conferment of E.A., F.C., and

M.M. Degrees 373

182. When to turn the Tracing Board 375

183. H.R.H., The late Duke of Windsor, 18941972 376

184. Tying the Aprons; strings at front or back? 377

185. The Junior Warden as `ostensible Steward' 378

186. The National Anthem and the Closing Ode 379

187. Salute in passing 379

188. Formal investiture of officers 380

189. The Chisel and its symbolism 384

190. Absent Brethren; the nine-o'clock Toast 386

For particular subjects please use the Index

CONTENTS xv

Page

191. Solomon and his Temple in the Masonic system 387

192. Presentation to the Board of Installed Masters 388

193. Grand Honours 392

194. Visitors' greetings to the Master 393

195. Overloading the ceremonies 394

196. The family tree of the Craft, Royal Arch, and Mark 395

197. Knocks when calling the Tyler 396

198. The preliminary step to `entrusting' and `communication' 397

199. The I.P.M.'s salutes in closing after each Degree 398

200. Masonic statistics. How many lodges, Grand Lodges,

Freemasons? 399

201. The Origin of the Points of Fellowship 403

List of Illustrations and Diagrams

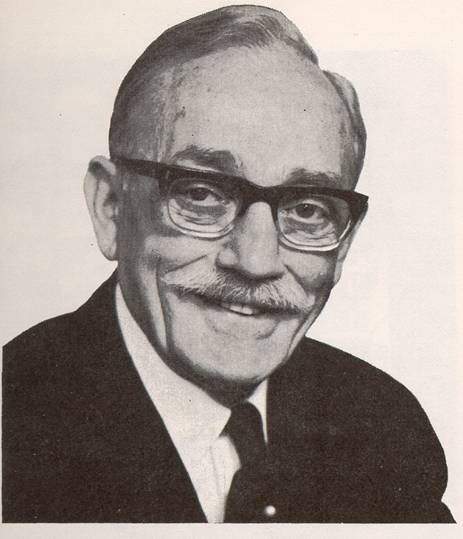

Frontispiece: The Author

The Quatuor Coronati (from the Isabella Missal, c. 1500) 1

The Grand Master's Jewel 4

Arms of the London Masons' Company 15

Arms of the Antients' Grand Lodge 17

Arms of the United Grand Lodge 19

L.F. across the Lodge 20

Tracing Board of the 2°; winding stairs anti-clockwise 37

clockwise 37

Ladder symbols on 1 ° Tracing Board by Bro. Esmond Jefferies 119

including the Key 119

Aprons, flap up, corner up 141

William Preston 153

Seating at Table 175

Illustration of the M.M. Degree (French) 1745 190

The circle of swords, 1745 195

Floor-drawing of the Third Degree; Le Macon Demasque, 1751 197

Pillars with `bowls', not `globes' 273

Tracing Board of the 3°, with Hebrew inscription 325

Jewel of the Grand Pursuivant 337

For particular subjects please use the Index

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

A.: Answer L.G.R.: London Grand Rank

A. & A.S.R.: Ancient and Accepted Leics.: The Leicester Lodge of Scottish Rite Research, No. 2429

Antients: The Grand Lodge of L. of I.: Lodge of Instruction

England according to the Old L. of R.: Lodge of Research

Institutions, 17511813 Miller, A.L.: Notes on Hist. . . . of

AQC: Ars Quatuor Coronatorum. the Lodge of Aberdeen. . . (1919)

(Transactions of the Quatuor Misc. Lat.: Miscellanea Latomorun:

Coronati Lodge) M.M.: Master Mason

Asst.: Assistant Moderns: The premier Grand

Bd.: Board Lodge, 17171813

B.G.P.: Board of General Purposes M.W.: Most Worshipful

B. of C.: Book of Constitutions Ob.: Obligation

B. of I.M.: Board of Installed O.E.D.: The Oxford English

Masters Dictionary

Brn.: Brethren O.T.: The Old Testament

Cand.: Candidate P.: Past

Catechisme: Le Catechisme des Pen. Sn.: Penal Sign

Francs-Masons, 1744 p.g.: pass grip

C.C.: Correspondence Circle (of the P.M.: Past Master

Q.C. Lodge) Pres.: President

Claret: The Ceremonies of Initiation, Prov.: Provincial

Passing and Raising . . . 1838, etc. p w: password

D.C.: Director of Ceremonies Q.: Question

Deg.: Degree Q. and A. Question and Answer

Demasque: Le Macon Demasque, Q.C.: Quatuor Coronati (Lodge)

1751 Q.C.A.: Quatuor Coronatorum

Dep.G.: Deputy Grand Antigrapha (Masonic Reprints)

Dist.G.: District Grand R.A.: Royal Arch

E.C.: English Constitution R.W.: Right Worshipful

E.F.E.: The Early French Exposures, S.C.: Scottish Constitution

1971 Sec.: Secretary

E.M.C.: The Early Masonic Cate- Secret: Le Secret des Francs-

chisms, by Knoop, Jones and Macons, 1742

Hamer, 2nd edn., 1963 Sn.: Sign

E.R.H.MS.: The Edinburgh Register T.D.K.: Three Distinct Knocks, 1760

House MS., 1696 Tn.: Token

F.C.: Fellowcraft Trahi: L'Ordre des Francs-Macons

F.P.O.F.: Five Points of Fellowship Trahi, 1745

G.: Grand U.G.L.: United Grand Lodge of

G.L.: Grand Lodge England

G.M.: Grand Master Vernon, W.F.: Hist. of Free-

H.A.: Hiram Abif masonry in the Province of

IG.: Inner Guard Roxburgh . . . (1893)

J. & B.: Jachin and Boaz . . . 1762 V.S.L.: Volume of the Sacred Law

K.S.T.: King Solomon's Temple

INTRODUCTION

THE origins of this book are, in fact, a part of the history of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge and it is fitting that I begin by paying a richly deserved tribute to my predecessor in office, the late Bro. John Dashwood. He had been appointed Secretary of the Lodge and Editor of its Trans‑actions in 1952, at a time when the membership of the Correspondence Circle had reached its supposed peak, around 3,000, and the production of the annual volumes had fallen several years in arrears.

By slimming the volumes severely during the next few years, he managed to catch up on arrears of publication. In 1960, the Lodge Standing Committee was compelled to deal with its most urgent problem, i.e., a substantial increase in income, necessitating a rapid expansion in the membership of the Correspondence Circle, which was practically its only source of revenue.

As a very junior Past Master of the Lodge, I had been arguing for some time that we were concentrating on scholarly material in the Transactions which could only be appreciated by the select few, and I urged that we should bring into our publications a few simple Lectures, Questions and Answers, etc., that would be suitable for `the boys at Lodge of Instruction'. This suggestion caused some dismay at first, and there were murmurings about `the lowering of standards'. I protested that the new material would be in addition to our main work, so that it would not in any way affect the quality of the Transactions, but would simply make them attractive to a completely new field of readers.

John Dashwood sympathized with my views and eventually the opposition was won over. For the proposed addition to the volumes, it was resolved to revive Miscellanea Latomorum, a Masonic magazine which had ceased publication in 1950. The copyright belonged to the Quatuor Coronati Lodge. In its new form, as an eight‑page pamphlet, it would be sent annually to all members without extra charge. The first issue contained a short paper by Bro. John Rylands on `The Ancient Landmarks', followed by fifteen questions, including some that were very abstruse. Only eight of them were answered, leaving seven that necessarily remained in limbo until the next year's volume! As to `lowered standards', it is amusing to note that the first issue was

xvii

xviii INTRODUCTION

loosely inserted in the Transactions as a separate pamphlet, to ensure that its contents would not contaminate the main volume with which it was posted! The results were far better than we dared to hope, and the end of that year showed a satisfying increase in membership and funds. Unfortunately Bro. Dashwood did not live to enjoy the fruits of his labours. He went into hospital in May 1961, and died after a very brief illness. There was no successor ready to replace him, and after a few months' trial period (doing the editorial work at home, at night and week‑ends) I retired from business in September 1961, to become Secretary and Editor, and to start on the happiest and most productive twelve years in a long and busy lifetime.

Uneasy and diffident, because I had had no preliminary training for the work, it was an incident in the first week of that trial period that determined me to accept the office and to make a success of it. In one day's post there were two letters, one from Alaska asking for guidance on the correct procedure for balloting in lodge and the other was from Australia requesting a ruling on a piece of `floor‑work'. I knew, of course, that there were members of the Correspondence Circle in many parts of the world; but two questions in one day from places almost as far apart as it was possible to be, made me realize suddenly how important our educational programme could become if it was handled properly. From that day onwards the Questions and Answers for the new venture became a major concern. But, in future, the items selected for publication were to be of the highest popular appeal, on subjects that would stimulate discussion and prove both instructive and entertaining, especially to those Brethren who know little or nothing of the background of Freemasonry beyond what they have seen or heard in lodge.

As part of the same programme, the Lodge Summonses were enlarged from two pages to four, the additional space being used for shorter Questions and Answers. As the Summonses were posted six times a year, it was hoped that they would help to maintain a closer contact with the Brethren for whom they were designed.

The first version of Misc. Lat., produced under my supervision, was bound in with AQC, Vol. 74, and contained four short Lectures designed for use in lodge, with a block of Questions, Answers and Notes, twenty‑eight pages in all, under a new heading `THE SUPPLEMENT'. It created something of a sensation; clearly we had opened up a Masonic gold‑mine! Soon, we were averaging more than 1,000 new members each

INTRODUCTION xix

year. In 1973 the membership of the Correspondence Circle was 12,440.

Eventually letters began to come in, urging us to publish the whole collection of Questions and Answers in book form. As author of nearly all the answers, I was eager to fulfil these requests, but that could not be done at once. Because of our rapid expansion and limited staff, much of the material had been written under pressure, with the printers waiting for every page. The Answers, especially in the Lodge Summonses, had often been skimped because of limited space and, after publication, many of the items had brought comments from readers, raising points of high interest that deserved to be included in a `collected edition'.

Although the original material was already in print, it was clear that a great deal of editorial work would need to be done to prepare it for the new publication; but that had to wait until my retirement from office. Here are the results, the fruits of twelve years work.

THE QUESTIONS AND THEIR TREATMENT

The questions that come to us at Q.C. deal, almost invariably, with matters on which there is no Grand Lodge ruling, or on which the printed rituals and their rubrics afford little or no explanation. They fall mainly into two classes:

Those which ask for the meaning and purpose of a specific item of ritual or procedure, or how and why it arose.

Those which describe two different versions of ritual or procedure and ask `Which is correct?'

Generally I believe the historical approach is the most rewarding, i.e., tracing the item in question from its earliest appearance, and following its development and changes up to the time when our ritual and procedures were more‑or‑less standardized in the early 1800s. When, as often happens, no definite conclusion is possible, this method sets out the information that may lead to a probable answer and, at the very least, it gives the enquirer a wider knowledge and a better understanding of the problems that are involved.

Because the printed pieces were intended for a world‑wide circulation, my answers always tried to give a little more than the questioner had asked. I make no apology for that, since we had strong encouragement from our readers, and the regular yearly figures of increasing member‑ship were ample proof of a steadily growing demand for our work.

xx INTRODUCTION

Among the questions that are not easily answered, are those that ask for explanations of incidents and details in the Craft legends and allegories, in which the enquirers treat each item as though it is proven fact, supported by Holy Writ! I remember the day, more than forty years ago, when a Grand Officer - looking me straight in the eye - assured me that Moses was a Grand Master! My grounding in Old Testament refuted this utterly, but I was a young Master Mason and one does not shatter a man's illusions lightly. In dealing with questions of this kind, it is imperative to separate legend from fact; the difficulty lies only in framing the answers so that they do no hurt or damage.

Inevitably, there are questions on esoteric matters of ritual and procedure that cannot be discussed in print and those are often of the highest interest. In such cases, the only practicable course is to go back to the earliest version of the item in question, tracing its development throughout the centuries, but stopping short at the final standardization and changes that were made in the 19th century, when most of the forms in use today were established. This does not answer the question, it only points the way so that the enquirer may be enabled to find the answer for himself. I must, therefore, repeat a warning which has been given on many similar occasions: In dealing with certain ritual and procedural matters, the reader's attention is particularly directed to the fact that the articles in this volume quote from documents of the 14th‑18th centuries, and that the details that are described belong only to the dates that are assigned to them. They take no account of the changes and standardization that took place in the 19th century, and it is emphasized that, except in a few innocuous cases, they do not describe - or attempt to describe - present‑day practices.

Finally, the articles in this book were never intended to be the last word on those subjects. They are simply a collection of careful answers, at an elementary level (often only my own opinion) on the queries and problems that arise in the lodge room, from Brethren who are eager for a better understanding of the things that they say and do in the course of their Masonic duties. That explains the title, `The Freemason at Work'. It is hoped that the whole collection will furnish an ample choice of subjects for discussion in lodges and Study Groups, and bring new pleasures to Brethren who enjoy their Masonry.

INTRODUCTION xxi

THE INDEX

In every work of this kind, the Index is as important as the book itself. For every reader in pursuit of a particular theme, it will be invaluable. All the Questions are numbered for easy reference, but for the reader in search of a particular theme or subject, the Index will be the most speedy guide.

COPYRIGHT

For copyright reasons, the present volume contains only my own work, supplemented in many instances by quotations from other writers with their permission, and with due acknowledgment.

Recognized lodges, Study Groups and individual Brethren have full permission to make use of the contents, but none of the articles may be reproduced or published without written permission from the author.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I take this opportunity to express my indebtedness to the Librarians of Grand Lodge and their Assistants during the past twenty years, for their generous and unstinted help at all times and, especially, to the present Librarian, Bro. T. O. Haunch. My thanks also to Bro. Roy A. Wells, my successor in office and to Bro. Colin F. W. Dyer who furnished valuable additions to several of the answers, which are gratefully acknowledged here and in the text. I am particularly indebted to Bro. Frederick Smyth for the very comprehensive Index and to R.W.Bro. Sir Lionel Brett for his kindness in writing the Foreword to the book and for his ready help in Latin and other editorial problems during the years. Lastly, my thanks to the Board of General Purposes of the United Grand Lodge of England for their kind permission to quote from the Constitutions and other official documents and from rare manuscripts in the Grand Lodge Library.

LONDON H.C.

December 1975

Blank page

THE FREEMASON AT WORK

1. THE QUATUOR CORONATI

Q. What does the name `Quatuor Coronati' mean?

A. The Latin words mean `the four crowned ones' and allude to the Christian Church's Festival of the Four Crowned Martyrs, which is celebrated on 8 November annually.

There are numerous versions of the legend of the Sancti Quatuor Coronati, all very much alike, though they differ considerably in important details such as their nationality, their number, and even their names.

The story, in brief outline, is that in A.D. 302 four stone‑carvers and their apprentice were ordered by the Emperor Diocletian to carve a statue of Aesculapius, which, since they were secretly Christians, they evaded doing. For disobedience to the Emperor's commands they were put to death on 8 November. During the year 304 Diocletian ordered that all Roman soldiers should burn incense before a statue of the same god, when four who were Christians refused to do so, for which they were beaten to death. This was also said to have been on 8 November, though two years later than the stone‑carvers.

Melchiades, who was Pope from A.D. 310 to 314, ordained that these two sets of four and five martyrs were to be commemorated on

1

2 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

November 8, under the single name of Quatuor Coronati. The Sacramentary of Pope Gregory, two hundred years later, confirmed that date and Pope Honorius built a church in their honour in the seventh century. They are to be found to this day, depicted in sculpture and painting, in many mediaeval and later churches in Europe.

The Saints are referred to in the earliest known version of the Old Charges, the Regius MS., which is dated c. 1390 and there is good evidence that they were venerated by English masons, notably in an ordinance of the London masons, dated 1481 and still preserved in the Guildhall archives, which prescribed that ... every freeman of the Craft shall attend at Christ‑Church [Aldgate] on the Feast of the Quatuor Coronati, to hear Mass, under a penalty of 12 pence.

The founders of our Lodge, nine in number, of whom four were soldiers, chose Quatuor Coronati as the name of the Lodge and November 8 has been the date of the annual Festival and Installation meeting since its foundation.

2. THE BRIGHT MORNING STAR

Q. When we are exhorted, in the Third Degree, to lift our eyes to that bright morning star, whose rising brings peace and salvation . . .' are we referring to a particular star, or is this pure symbolism?

A. The various aspects of this problem may be best envisaged, perhaps, from the following quotations, beginning with some extracts from Miscellanea Latomorum, (Series ii) Vol. 31, pp. 1 - 4:

It is argued that this reference to `that bright Morning Star' is an allusion to the Founder of Christianity, and as such should never have been included in, or retained in, the ritual of an Association professing entire freedom from denominational creed or dogma, outside of the simple basic belief in the existence of a Supreme Being. This attitude has unfortunately been bolstered up by a frequent misquotation of the wording, the phrase `whose rising brings peace and tranquillity' being often rendered as `peace and salvation', which is erroneous and decidedly mischievous. [N.B. Emulation, Stability and Logic use the word `salvation'; Exeter says `tranquillity'.]

As a symbol, the Morning Star is indeed most appropriate to the ceremonial incident just previously enacted; so apt, in fact, that it may be confidently asserted that no other symbol could be found which would so perfectly fit the circumstances of the case. Astronomically the Morning Star is the herald of the dawning of a new day, just as its opposite, the Evening Star, presages the coming of night. The latter foretells the dying of another day; the approach of the time when man can no longer work; when darkness covers the face of the earth. Darkness has ever been associated with

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 3

evil, and in its sombre, unknown possibilities is a fitting emblem of death. On the other hand, the rising Morning Star brings joy and gladness with its promise of yet another day, of light once more, in which man may work and renew his association with his fellow‑man in business or in pleasure. In short, with the new‑born day, man rises to a new life. What more fitting symbol, then, than this of the promise of new life after death - of the immortality of the soul.

The late Dr. E. H. Cartwright, in his Commentary on the Freemasonic Ritual, (2nd edn., 1973, p. 186), wrote, with customary forthrightness:

`That bright morning star'. It should, of course be `that bright and morning star', the phrase being a quotation from The Revelation, xxii, 16. The reference is definitely to Christ and is a relic of the time when the Craft was purely Christian. The allusion apparently escaped the notice of the revisers at the Union, when Christian references generally were excised. Some hold that, as we are not now exclusively Christian, but admit Jews, Moslems and others who, though monotheists, are not Christians, this reference should be deleted, as others of a like nature have been. If the phrase be objected to, the Revised Ritual provides an appropriate alternative rendering, namely, `and lift our eyes to Him in whose hands are the issues of life and death, and to whose mercy we trust for the fulfilment of His gracious promises of Peace and Salvation to the faithful etc.' My own view is that the reference to the `Bright Morning Star' would be quite inexplicable if we read it in an astronomical sense, to imply that a particular star can bring peace, or tranquillity, or salvation, to man‑kind. As a Christian reference, moreover, this passage must cause embarrassment to Brethren who are not of that Faith and in two of my Lodges (of mainly Jewish Brethren) where this point arose, we now use the following: ... and lift our eyes to Him whose Divine Word brings Peace and Salvation to the faithful, etc.

This form of wording has two great advantages:

1. It provides a definite meaning to the passage instead of an ambiguous one.

2. It is in full accord with Masonic teaching and respects the religious beliefs of all the participants.

3. THE COMPASSES AND THE GRAND MASTER

Q. Why are the Compasses said to belong to the Grand Master?

A. Early official documents, i.e., the Books of Constitutions and the Grand Lodge Minutes, afford no information on this point. Jewels are

4 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

mentioned in the Constitutions from 1738 onwards and frequently in the Grand Lodge Minutes from 1727 onwards, but the Grand Master's Jewel was not described in detail until the 1815 B. of C. It was to be of `gold or gilt' and made up as follows:

The compasses extended to 45°!, with the segment of a circle at the points and a gold plate included, on which is to be engraven an irradiated eye within a triangle.

The Grand Master's Jewel

By courtesy of the Board of General Purposes

Nowadays, the triangle is also irradiated. It should be noted, however, that from 1815 onwards the Jewel contains several items in addition to the compasses.

The only hint, in a more‑or‑less official publication, suggesting that the compasses belong to the Grand Master, appears in the frontispiece to the first Book of Constitutions, 1723, which shows the Duke of Montagu handing a pair of compasses and a scroll to his successor, the Duke of Wharton, and there are no other tools in the picture. It would be unsafe to draw any firm conclusions from this item, because there are several documents from this period which show that the compasses belonged to the Master, not to the Grand Master. The earliest of these is the Dumfries No. 4 MS., c. 17101 (i.e. seven years before the election of the first Grand Master):

1 See p. 5, footnote 1.

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 5

Q. would you know your master if you saw him?

A. yes

Q. what way would ye know him?

A. by his habit

Q. what couller is his habit?

A. yellow & blew meaning the compass wc is bras & Iron Very crude, but twenty years later the same theme appeared in better detail in a newspaper exposure, now generally known as The Mystery of Free‑Masonry, 17301:

Q. How was the Master cloathed?

A. In a Yellow Jacket and Blue Pair of Breeches.*

* N.B. The Master is not otherwise cloathed than common; the Question and Answer are only emblematical, the Yellow Jacket, the Compasses, and the Blue Breeches, the Steel Points.

Two months later, in October 1730, Prichard, in his Masonry Dissected, repeated this Q. and A., almost word for word, omitting only the first half of the N.B., i.e., he discarded the emblematical suggestion, thereby implying that the compasses were indeed part of the Master's regalia. Elsewhere, however, he had a note that the Master, at the opening of a Lodge, had `the Square about his neck'. The Wilkinson MS., c. 1727, agreed with Prichard on the compasses but omitted the reference to the Square.

In 1745, a popular French exposure, L'Ordre des Francs‑Masons Trahi, in which the catechism was substantially based on Prichard, dealt more fully with the same question:

Q. Have you seen the Grand Master? [= the W.M.]

A. Yes.

Q. How is he clothed?

A. In gold & blue. Or rather; In a yellow jacket, with blue stockings.

This does not mean that the Grand Master is dressed like that: but the yellow jacket signifies the head and the upper‑part of the Compasses, which the Grand Master wears at the bottom of his Cordon, & which are made of gold, or at least gilt; & the blue stockings, the two points of the Compasses, which are of iron or steel. That is what they mean also, when they refer to the gold & blue.

The title `Grand Master' was used quite loosely, in this text and in French practice at that period, to mean the Worshipful Master and the context of this quotation proves this beyond doubt.

It was not until the last quarter of the 18th century that the earliest English texts began to say that the compasses belonged to the Grand Master. The first of these was probably William Preston's version, in

1 Reproduced in The Early Masonic Catechisms, 2nd edn. (1963) pub]. by the Quatuor Coronati Lodge, London.

6 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

his `First Lecture of Free Masonry' (which was reproduced by Bro. P. R. James, in AQC 82, pp. 104 - 149):

Why are the compasses restricted to the Grand Master? The compasses are appropriated to Master Masons [sic] because it is the chief instrument used in the delineation of their plans and from this class all genuine designs originate. . . . As an emblem of dignity and excellence the compasses are pendent to the breast of the Grand Master to mark the superiority of character he bears amongst Masons. (See AQC 82, p. 138)

Preston wrote with his customary verbosity and his reference to Master Masons is rather confusing. The date of this version is uncertain, probably around 1790 - 1800. Later writers were more specific. Browne's Master Key (2nd ed.) appeared, mainly in cipher, in 1802:

Why the Compasses to the Grand Master in particular? The Compasses being the chief instrument made use of in all plans and designs in Geometry, they are appropriated to the Grand Master as a mark of his distinction... .

Richard Carlile, in the Republican, 15 July 1825, wrote:

The compasses belong to the Grand Master in particular, and the square to the whole craft.

Claret, 1838, also dealt with this question, and his answer has become standard in most modern versions of the Craft Lectures:

That being the chief instrument made use of in the formation of all Architectural plans and designs, is peculiarly appropriated to the Grand Master, as an emblem of his dignity, he being the chief head and ruler of the craft.

Nowadays, a reference to the Jewels illustrated in the Book of Constitutions will show that the Compasses form a part of the Jewel of all the following:

1. The Grand Master 2. Past Grand Master

3. Pro Grand Master 4. Past Pro Grand Master

5. Deputy Grand Master 6. Assistant Grand Master

7. Prov. or Dist. Grand Master 8. Past Prov. or Dist. Grand Master

9. Grand Inspector 10. Past Grand Inspector

4. IT PROVES A SLIP

Q. `It proves a slip'. How did those words arise?

A. Those words are the last relic of something that was a distinct feature of all early versions of the third degree. If one were challenged today to describe the lessons of the third degree in three words, most Brethren would say `Death and Resurrection', and they would be right;

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 7

but originally there were three themes, not two, and all our early versions of the third degree confirm three themes, `Death, Decay and Resurrection'. Any Brother who has a compost heap in his garden will see the significance of this `life‑cycle'.

Eventually, the decay theme was polished out of our English ritual, but `the slip' which is directly related to that theme remains as a re‑minder of the degree in its early days.

The first appearance of `the slip' in a Masonic context was in Samuel Prichard's Masonry Dissected, of 1730. That was the first exposure claiming to describe a system of three degrees and it contained the earliest known version of a Hiramic legend. Prichard's exposure was framed entirely in the form of Question and Answer and the main body of his legend appears in the replies to only two questions.

Many other and better versions have appeared since 1730, but Masonry Dissected (though it gives no hint of a long time‑lag which might have caused decay) was the first to mention `the slip' and to indicate that the cause was decay. The words occur in a footnote to the so‑called `Five Points of Fellowship'.

N.B. When Hiram was taken up, they took him by the Fore‑fingers, and the Skin came off which is called the Slip; .. .

The next oldest version of the third degree was published in Le Catechisme des Francs‑Masons, in 1744, by a celebrated French journalist, Louis Travenol. It was much more detailed than Prichard's piece, and full of interesting items that had never appeared before. In the course of the story we learn that nine days had passed when Solomon ordered a search, which also occupied a `considerable time'. Then, following the discovery of the corpse,

. . . One of them took hold of it by one finger, & the finger came away in his hand: he took him at once by another [finger], with the same result, & when, taking him by the wrist it came away from his arm . . . he called out Macbenac, which signifies among the Free‑Masons, the flesh falls from the bones.... 1

In 1745, Travenol's version was pirated in L'Ordre des Francs‑Masons Trahi, but there were a few improvements:

... the flesh falls from the bones or the corpse is rotten [or decayed] 2

The English exposure Three Distinct Knocks, of 1760, used the words `almost rotten to the bone', but before the end of the 18th century the

1 Early French Exposures, pp. 97‑8.

2 E.F.E., p. 258.

8 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

decay theme seems to have gone out of use in England, so that `the slip', in word and action, remains as the last hint of the story as it ran in its original form. But the decay theme is not completely lost; several ritual workings, in French, German, and other jurisdictions, still retain it as part of their legend.

One more document must be quoted here, because it has particularly important implications. The Graham MS., of 1726, is a unique version of catechism plus religious interpretation, followed by a collection of legends relating to various biblical characters, in which each story has a kind of Masonic twist. One of the legends tells how three sobs went to their father's grave

for to try if they could find anything about him ffor to Lead them to the vertuable secret which this famieous preacher had. . . . Now these 3 men had allready agreed that if that if they did not ffind the very thing it self that the first thing that they found was to be to them as a secret . . . so came to the Grave finding nothing save the dead body all most consumed away takeing a greip at a flinger it came away so from Joynt to Joynt so to the wrest so to the Elbow so they R Reared up the dead body and suported it setting ffoot to ffoot knee to knee Breast to breast Cheeck to cheeck and hand to back and cryed out help o ffather . . . so one said here is yet marow in this bone and the second said but a dry bone and the third said it stinketh so they agreed for to give it a name as is known to free masonry to this day. . . . (E.M.C., pp. 92‑3).

The decay theme again, but the important point about this version is that the `famieous preacher' in the grave was not H.A., but Noah, and the three sons were Shem, Ham, and Japheth. The appearance of this legend in 1726, full four years before the earliest H.A. version by Prichard, implies, beyond doubt, that the Hiramic legend did not come down from Heaven all ready‑made as we know it today; it was one of at least two (and possibly three) streams of legend which were adapted and tailored to form the main theme of the third degree of those days.

5. WHY TWO WORDS FOR THE M.M.?

Q. At a certain stage in the M.M. degree two words are uttered by the W.M. Why two?

A. There is ample evidence, from c. 1700 onwards, that only one word was conferred originally, though it appears in vastly different spellings and pronunciations. The earliest known version, in the Sloane MS., of c. 1700, certainly belongs to the period when only two degrees were

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 9

practised and, in the study of the evolution of the ritual, it is extremely interesting to find a feature of the original second degree making its appearance, ultimately, in the third.

At the end of 1725 there were already four different versions of the word in existence (two in manuscript and two in print) and before 1763 no fewer than eight versions had appeared in England alone. Whatever they were originally, by the time we find them in our early documents it would be fair to describe them as non‑words, because they do not belong to any known language. As examples of debasement, Sloane gives the word(s) as Maha - Byn, half in one ear and half in the other; it was apparently used in those days as a test word, the first half requiring the answer `Byn'. Other early versions were `Matchpin', 1711, and `Magbo and Boe', 1725.

It is generally agreed that the words were probably of Hebrew origin (in which case each of them would be a combination of two words, i.e., verb and noun); but from the time of their first appearance, either in MS. or print, they were already so debased, through ignorance or carelessness, that it is impossible to say how they were written or pronounced in their original form.

There are various printed exposures of 1760, 1762 and later, which suggest that the word was pronounced differently by adherents of the rival Grand Lodges, i.e., that the `Moderns' used a form ending in a CH, CK, or K sound, while the `Antients' used a form which finished with an N sound. This would seem to be a generalization that must be discounted, because there were three N versions in c. 1700, 1711 and 1723 respectively, decades before the Antients' Grand Lodge was founded.

Whether or not the rival Grand Lodges kept strictly to those forms (and we have to take note of the MS. catechisms and the printed exposures simply because there were no official pronouncements), the available evidence suggests that those were the two main forms in use in the English lodges throughout the 18th century.

Soon after the Lodge of Promulgation was erected (in 1809) to pre‑pare the way for the union of the two Grand Lodges, this point came into question while dealing with the form of `Closing the Lodge in the Third Degree', when the word is to be spoken aloud; but which word? It must have been a difficult problem, even for the distinguished members of that `Moderns' body, partly because none of them could be certain that the form to which they were accustomed was correct, but also because it was necessary to make allowance for the form in use by

10 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

the `Antients'. This predicament gave rise to a Resolution that they made on 16 February 1810, which is a model of wisdom and tolerance:

... but that Masters of Lodges shall be informed that such of them as may be inclined to prefer another known method of communicating the s [sic.? secrets] in the closing ceremony will be at liberty to direct it so if they should think proper to do so. (AQC 23, p. 42.)

The special Lodge of Promulgation was a Moderns' body, but one of its members, Bro. Bonnor, was acknowledged to have an accurate knowledge of the Antients' ritual, and it is possible that this resolution was framed out of respect for the rival body, or because no compromise was possible.

Many of us must have heard some of the extraordinary pronunciations given to those `Words' in our present‑day Lodges, and I am inclined to believe that the alternate forms were approved simply because nobody could be sure which of them, if any, was correct.

6. APPRENTICE AND ENTERED APPRENTICE

Q. As used in Freemasonry today, are the terms Apprentice and Entered Apprentice interchangeable?

A. Under Art. ii of the Articles of Union, it was `... declared and pronounced that pure Ancient Masonry consists of three degrees, and no more; Vizt. those of the Entered Apprentice, the Fellow Craft . . .', etc. Strictly speaking, therefore, the only title for the first grade in the Craft nowadays is Entered Apprentice, and the title Apprentice could only stand as an abbreviation.

It is necessary to go back to early operative practice to explain the real difference between the two terms. Apprentices were usually indentured to their Masters for seven years, and in Scotland there is evidence that the Masters undertook to `enter their apprentices' in the Lodge during that period. 1 In Edinburgh, it was the rule that all apprentices had to be `booked' in the town's Register of Apprentices, at the beginning of their indentures. The Register survives from 1583 and shows that the `bookings' recorded the names of the apprentice and his father, the father's trade and place of residence, the name, trade and residence of the master, the date of the `booking' and (rarely) the actual date of the indentures - if there had been any delay in the `booking'.

1 See `Apprenticeship in England and Scotland up to 1700', by H. Carr, AQC 69, pp. 57/8, 67/8); also `The Mason and the Burgh', AQC 67.

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 11

These carefully detailed municipal records become valuable indeed when, from 1599 onwards, there are minutes for the Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary's Chapel), in which it is possible to identify more than a hundred apprentices and to check the dates when they were admitted into the Lodge as `entered apprentice'. This usually happened some two to three years after the beginning of their indentures, and that marked the beginning of their career within the Lodge.

They would normally pass F.C. about seven years after they were made E.A., or roughly ten years from the commencement of their training. If for any reason they failed to pass F.C., they retained their Lodge status as E.A., even after their term of service had finished and they were already working as journeymen.

The Edinburgh system of introducing the apprentice into the Lodge during his apprenticeship did not exist in 1475, when the Masons and Wrights Incorporation [= Gild] was founded, but it was already fully established in 1598 when the earliest surviving Lodge minutes begin. The two to three‑year time lag between `booking' and E.A. may have been longer in other places. Unfortunately, it is only Edinburgh that still possesses the dual town‑and‑Lodge records, that enable us to verify their practice.

It is curious that the term `entered apprentice' does not appear in English documents until the 1720s.

7. THE TITLES OF THE UNITED GRAND LODGE OF ENGLAND

Q. What is the official title of the Grand Lodge of England? Here in the U.S.A. our Grand Lodges are F. & A.M., or A.F. & A.M., and this carries on down to the local Lodges. My own Lodge is commonly known as St. John's Lodge, No. 17, A.F. & A.M., yet I can find no reference to the full titles of Lodges operating under English jurisdiction. I find many references to the United Grand Lodge, but the United Grand Lodge of what?

A. The United Grand Lodge was erected in 1813 by a union of the so‑called Antients' and Moderns' Grand Lodges under the Articles of Union, a lengthy document which outlined the conditions agreed for the government of the new body. The Articles were signed on 25 November 1813, and ratified by both Grand Lodges meeting independently six days later. Article vi declared that:

12 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

... the Grand Incorporated Lodge shall ... be opened ... under the stile and title of the United Grand Lodge of Ancient Freemasons of England.

On 27 December 1813, a Grand Assembly of Freemasons was held to give effect to the union, and the new organization was duly proclaimed under that title.

The first Book of Constitutions to be published after the union appeared in 1815, and the General Regulations were headed by a brief statement which gave a new title to the Grand Lodge: THE public interests of the fraternity are managed by a general representation of all private lodges on record, together with the present and past grand officers, and the grand master at their head. This collective body is stiled the UNITED GRAND LODGE OF ANTIENT FREE AND ACCEPTED MASONS OF ENGLAND .. .

The earlier title, incorporating the expression `Antient Freemasons of England' (but with the word `Antient' spelt with a `t' instead of a `c'), appeared in the printed record of Grand Lodge proceedings of March, May, June and September 1814, the word Free‑Mason having a hyphen in May, June and September. It reappeared with a hyphen in the record of an Especial Grand Lodge in February 1815.

In May 1814, the Duke of Sussex was proclaimed as Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of `Antient Free‑Masons of England', and in December 1814, he was proclaimed as G.M. of the United Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of England.

The reasons for the changes in nomenclature at this period are not apparent, but it must be inferred that the change from the expression `Ancient Freemasons' of 1813 to the `Antient Free and Accepted Masons' of 1815 was deliberate - a change which has been preserved in all subsequent editions of the Book of Constitutions to the present day. (Extracts from Notes compiled by Bro. W. Ivor Grantham.) Strictly speaking, all English Lodges should add the A.F. & A.M. to their titles, but the practice is extremely rare.

8. EVERY BROTHER HAS HAD HIS DUE

Q. What is the real meaning of the Senior Warden's words in closing the lodge, `... to see that every Brother had had his due.'?

A. This is an archaic survival, almost meaningless today. Yet the principle upon which it is based is one of the oldest in the English Craft,

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 13

and its origins are to be found in our earliest operative documents, the Old Charges, or MS. Constitutions, which afford useful information on the management of large‑scale building works in the 14th and 15th centuries.

To appreciate the full significance of these words, we may forget the lodge for the present, and go to the site where the works were in progress. In those days, the Warden (and there was only one Warden) was a kind of senior charge‑hand, or overseer. Nowadays, we might call him a `progress‑chaser' and it was a part of his duties to ensure that nothing disturbed the smooth progress of the work.

If a dispute arose between any of the masons in his charge, he had to mediate and try to settle it on the spot and with absolute fairness, so that `every Brother had his due'. If the trouble was too difficult to be settled at once, he had to fix what was called a `loveday', which was a day appointed for the amicable settlement of disputes; but meanwhile, everyone had to get on with his work. The regulations specified that the 'loveday' was to be held on a `holy day', not a working day, so that the works would not suffer to the employer's detriment. (Cooke MS., c. 1400, Point vi.) The same text, at Point viii continues: ... if it befall him for to be warden under his master that he be true mene [= mediator] between his master and his fellows and that he be busy in the absence of his master to the honour of his master and profit of the lord [= employer] that he serves.l The Regius MS., c. 1390, does not mention the warden in this con‑text, but speaks of one who has taken a position of responsibility under his master:

A true mediator thou must need be,

To thy master and thy fellows free,

Do truly all [good?] that thou might,

To both parties, and that is good right. 1

The same theme runs regularly through many of the old Constitutions, requiring the wardens to preserve harmony amongst the men under their care, by mediating fairly in any dispute that might arise, and thereby ensuring `that every Brother had his due'.

Finally, there are many versions of these words in our modern rituals, including one which runs `... to pay the men their wages and see that every Brother has had . . .'. A careful examination of the texts

1 From The Two Earliest Masonic MSS., pp. 122‑5. By Knoop, Jones and Hamer. Quotations word for word, but in modern spelling.

14 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

that deal with the Warden's duties show that wages have nothing to do with this particular question.

9. ARMS OF THE GRAND LODGE

Q. What is the origin of the Arms of the United Grand Lodge of England?

A. The modern Arms are directly descended from three separate bodies, and their story begins in the 14th century, more than 300 years before the first Grand Lodge was founded.

THE LONDON MASONS' COMPANY

There are records at Guildhall in London which show that the Masons' Company was in existence in 1375. It was the first English Gild of the Mason trade and, in 1376, it elected representatives of the trade to serve on the Common Council, which was the organ of city government, proof of its status as one of the important city Companies.

The exact date of its foundation is unknown, but the roots of the Fellowship of Masons in England go back much further than that, to the year 1356, when twelve skilled master masons came before the Mayor and Aldermen at Guildhall, in London, to settle a demarcation dispute, and to draw up a code of trade regulations, because their trade had not, until then, `been regulated in due manner, by the government of folks of their trade, in such form as other trades' were.

This was the true beginning of mason trade organization in England, which gave rise to the `Hole Crafte & Felawship of Masons', later the London Masons' Company.

In 1472 it was given a Grant of Arms, which marked the highest form of official recognition of the Craft as one of the City Companies. The text of the Grant (with a few Anglo‑Norman words rendered in modern English) runs as follows:

To all Noblemen and gentlemen these present Letters hearing or seeing, William Hawkeslove, otherwise called Clarenceux King‑ of Arms of the South Marches of England, sends humble and due Recommendation as appertaineth.

For so much as the `Hole Crafte and Felawship of Masons' heartily moved to exercise and use gentle and commendable guidance in such laudable manner and form as may best appear unto the gentry, by the Which they shall move with God's grace to attain unto honour and worship, have desired and prayed me, the said King of Arms, that I, by the power and

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 15

Arms of the Masons Company as stamped on the covers of the

MS. Account and Court Books.

authority and by the King's good grace to me in that behalf committed should devise A Cognisance of Arms for the said Craft and fellowship which they and their successors might boldly and dutifully occupy, challenge and enjoy for ever more, without any prejudice or rebuke of any estate or gentlemen of this Realm. At the instance and request of whom, I, the said King of Arms, taking respect and consideration unto the goodly intent and disposition of the said Craft and fellowship, have devised for them and their successors the Arms following, that is to say,

A field of Sable, a Chevron of Silver, 1 grailed, three Castles of the same, garnished with doors and windows of the field,

In the Chevron, a Compass of Black, which Arms, I of my said power and authority, have appointed, given and granted to, and for, the said Craft and fellowship and their successors. And by these my present Letters, appoint, give and grant unto them the same, To have, challenge, occupy and enjoy, without any prejudice, or impeachment, for evermore.

In witness whereof, I, the said King of Arms, to these presents have set my seal of Arms, with my sign Manual.

Given at London, the year of the Reign of King Edward the fourth, after the Conquest the xijth.

Clarenceux Kings of Arms

W.H.

1 Note: it is a chevron, not a square.

16 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

This document gives us the earliest description of the design in black and silver, and, since 1472, the Arms reappear regularly - with occasional minor modification - in all sorts of Masonic documents. Many of the earliest versions of the MS. Constitutions, or Old Charges, from the 16th century onwards have the Arms emblazoned at their head. They are depicted in Stow's Survey of London, 1633, and we find them on tombstones, stained glass windows, and in architectural decoration, all over England. They are also depicted in the frieze of Arms of the City Companies which decorate the walls of Guildhall in London.

The original Grant contained no motto, and the earliest record of a motto attached to the Arms appears on the tomb of William Kerwin, dated 1594, in St. Helen's Church, Bishopsgate. It reads:

`God Is Our Guide'

The Company, indeed, has no authorized motto, but since the early 17th century, it appears to have used the words:

`In The Lord Is All Our Trust'

ARMS OF THE FIRST GRAND LODGE 1717‑1813

There is evidence that the premier Grand Lodge, founded in 1717, began to use the Masons' Company's Arms soon after its foundation, though the early minute books are silent on this subject. In 1729‑30, Thomas, 8th Duke of Norfolk, became Grand Master and, during his term of office, he presented to the Grand Lodge the Sword of State which is now borne in procession in Grand Lodge. Its silver‑gilt hilt and mountings and the scabbard were made in 1730 by George Moody, the Royal Armourer, who was the first Sword‑bearer of Grand Lodge, and the scabbard bears, inter alia, a reproduction of the Arms of the Masons' Company.

Despite the absence of any official record of the Arms being adopted by the Moderns' Grand Lodge, it was certainly using the `Three Castles, Chevron and Compass' as the central theme of its Seal before 1813, and a less ornate version as its `Office Seal'. Both are illustrated in Gould's History, 1951 edn., vol. II, fac. p. 275.

ARMS OF THE `ANTIENTS' GRAND LODGE 1751‑1813

The Most Ancient and Honourable Society of Free and Accepted Masons according to the Old Institutions was founded in London in July 1751. At that time it consisted of only six Lodges with a total membership of

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 17

some eighty Brethren. They were mainly artisans, tailors, shoemakers and painters `of an honest Character but in low Circumstances'; many of them were immigrants from Ireland or of Irish extraction.

In 1752, Laurence Dermott became their Grand Secretary and he held that office until 1771 when he became Deputy Grand Master. He was already Past Master of a Dublin Lodge and a recent immigrant from Ireland, originally a journeyman painter, but later a successful wine merchant. A man of some education and a born leader, he compiled Ahiman Rezon, the first Book of Constitutions of the new Grand Lodge and published it in 1756. Boasting always of their adherence to the `old System free from innovation' they soon became known as the `Antients' and they thrived.

Arms of the Antients' Grand Lodge, 1751‑1813.

The Arms of the Antients made their first appearance as the frontispiece to the 1764 edition of Ahiman Rezon, in which Dermott explained their origin at length:

18 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

N.B. The free masons arms in the upper part of the frontis piece of this book, was found in the collection of the famous and learned hebrewist, architect and brother, Rabi Jacob Jehudah Leon. This gentleman . . . built a model of Solomon's temple . . . This model was exhibited to public view ... at Paris and Vienna, and afterwards in London, ... At the same time ... (he) . . . published a description of the tabernacle and the temple,:. . I had the pleasure of perusing and examining both these curiosities. The arms are emblazoned thus, quarterly per squares, counterchanged Vert. In the first quarter Azure a lyon rampant Or, in the second quarter Or, an ox passant sable; in the third quarter Or, a man with hands erect, proper robed, crimson and ermin; in the fourth quarter Azure, an eagle displayed Or. Crest, the holy ark of the covenant, proper, supported by Cherubims. Motto, Kodes la Adonai, i.e., Holiness to the Lord.

... Spencer says, the Cherubims had the face of a man, the wings of an eagle, the back and mane of a lion, and the feet of a calf.

... Ezekiel says, . . . a man, a lion, an ox, and an eagle.

... Bochart says, that they represented the nature and ministry of angels, by the lion's form is signified their strength, generosity and majesty; by that of the ox, their constancy and assiduity in executing the commands of God; by their human shape their humanity and kindness; and by that of the eagle, their agility and speed.

It seems probable that Rabbi Leon had indeed sketched designs more or less related to this one which Dermott had adapted, but Leon cannot have designed the Motto, which was printed in faulty Hebrew.

The Masonic significance of the design (apart from the working‑tools at its foot) is closely related to the Royal Arch, and this was emphasized by Dermott's closing words on the subject: As these were the arms of the masons that built the tabernacle and the temple, there is not the least doubt of their being the proper arms of the ... fraternity of free and accepted masons, and the continual practice, formalities and tradition, in all regular lodges, from the lowest degree to the most high, i.e., The Holy Royal Arch, confirms the truth hereof.

ARMS OF THE UNITED GRAND LODGE

After 1751, the Antients' and Moderns' Grand Lodges existed side by side, not always without display of intense rivalry. In the late 1700s, however, there were many prominent Masons who held high rank in both bodies and in the early 1800s efforts were being made, behind the scenes, to effect a union. Eventually, and with the help of three Royal Brothers, all sons of George III, the negotiations proved successful and the Union took place in December 1813.

The Arms of the United Grand Lodge of England were a combination of the Arms of the Antients and Moderns, preserving the best features

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 19

Arms of the United Grand Lodge of England.

By courtesy of the Board of General Purposes.

of each, and the Hebrew inscription was corrected. In 1919, the shield was enhanced by a wide border bearing eight lions, suggesting the Arms of England and marking the long association of King Edward VII and many other members of the Royal Family with the Craft.

10. L.F. ACROSS THE LODGE

Q. Why do we tell the Candidate in the First Deg. to `Place your left foot across the Lodge and your r . . . f . . ., etc., heel to heel,' with similar but reverse procedure in the second? They seem to be awkward postures for the Cand. while he listens to the W.M.'s exhortation.

A. This is a survival from the time (probably before 1813) when it was customary to have the rough and smooth ashlars on the floor of the

20 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

Lodge, in the N.E. and S.E. corners, and not on the Wardens' pedestals, where they usually lie nowadays.

At the proper moment the Cand. was required to place his feet so that they formed a square on two sides of the ashlar, thus:

The N.E. corner The S.E. corner

The ashlars in the N.E. and S.E. corners, as shown in our sketch, are still to be seen there in many of our old English lodges, but rather rarely in London, where we have succumbed to modern customs. The postures, however, are still in use in most English lodges (not in all of them) even when the ashlars rest on the Wardens' pedestals.

The reason for the postures is, undoubtedly, purely symbolical and it can best be explained in the words of a writer (Fort Newton, I believe) who said that we enter the Craft in order `to build spiritual Temples within ourselves'. When we stand at the N.E. or S.E. corners to hear the exhortation from the W.M., we are participating in the dedication of our own spiritual Foundation‑stone.

There appears to be no satisfactory explanation for the awkward posture. It could be avoided, of course, if the Cand. stands facing E., or if the W.M. comes on to the floor for the exhortation.

It has been suggested that in earlier times, the N.E. and S.E. positions were at the immediate right and left of the W.M., so that the Candidates standing at those positions would have been more comfortably placed than they are today. The fact is that most of these procedures are inherited practices and we tend to preserve them, even when the reasons that gave rise to them are lost in the mists of time.

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 21

11. RAISING AND LOWERING THE WARDENS' COLUMNS

Q. Why do the Wardens in a Craft Lodge raise and lower their Columns? The usual explanations in the Lectures, etc., seem trivial, in view of the importance many Brethren seem to place on the Columns being moved at the right time and placed in the right position.

A. To find an acceptable answer to this question, we have to go back to early ritual. There was a time in 18th century English practice when both Wardens stood (or sat) in the West; this is confirmed by a passage in Masonry Dissected, 1730:

Q. Where stands your Wardens?

A. In the West.

Incidentally there are several Masonic jurisdictions in Europe which retain this ancient practice; but some time between 1730 and 1760 there is evidence that the J.W. had moved to the South, as shown in Three Distinct Knocks, 1760, and J. & B., 1762, both using identical words: Mas. Who doth the Pillar of Beauty represent? Ans. The Junior Warden in the South.

The business of raising and lowering the Wardens' Columns made its first appearance in England in Three Distinct Knocks, in which we have the earliest description of the procedure for `Calling Off' from labour to refreshment and `Calling On'. The `Call‑Off' procedure was as follows:

The Master whispers to the senior Deacon at his Right‑hand, and says, 'tis my Will and Pleasure that this Lodge is called off from Work to Refreshment during Pleasure; then the senior Deacon carries it to the senior Warden, and whispers the same Words in his Ear, and he whispers it in the Ear of the junior Deacon at his Right‑hand, and he carries it to the junior Warden and whispers the same to him, who declares it with a loud Voice, and says it is our Master's Will and Pleasure, that this Lodge is called from Work to Refreshment, during Pleasure;

At this point we find the earliest description of the raising and lowering of the columns and the reason for this procedure.

then he sets up his Column, and the senior lays his down; for the Care of the Lodge is in the Hands of the junior Warden while they are at Refreshment.

N.B. The senior and junior Warden have each of them a Column in their Hand, about Twenty Inches long, which represents the Two Columns of the Porch at Solomon's Temple, BOAZ and JACHIN.

J. & B. gives almost identical details throughout.

22 THE FREEMASON AT WORK

Unfortunately, apart from the exposures, there are very few Masonic writings that deal with the subject of the Wardens' Columns during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Preston, in several editions of his Illustrations, 1792‑1804, in the section dealing with Installation, allocates the Columns to the Deacons [sic]. It is not until the 1804 edition that he speaks of the raising of the Columns, and then only in a footnote, as follows:

When the work of Masonry in the lodge is carrying on, the Column of the Senior Deacon is raised; when the lodge is at refreshment the Column of the Junior Deacon is raised. [There is no mention of `lowering'.]

Earlier, in the Investiture of the Deacons, Preston had said:

Those columns, the badges of your office, I entrust to your care .. .

Knowing, as we do, that the Columns had belonged to the Wardens since 1760, at least, and that many of the Craft lodges did not appoint Deacons at all, Preston's remarks in the extracts above, seem to suggest that he was attempting an innovation (in which he was certainly unsuccessful).

The next evidence on the subject comes from the Minutes of the Lodge of Promulgation, which show that in their work on the Craft ritual in readiness for the union of the two rival Grand Lodges, they considered `the arrangements of the Wardens' Columns' on 26 January 1810, but they did not record their decision. We know, however, that most of our present‑day practices date back to the procedures which that Lodge recommended and which were subsequently adopted' - with occasional amendments - and prescribed by its successor, the Lodge of Reconciliation. It is thus virtually certain that our modern working in relation to the raising and lowering of the Columns was then adopted, following the 1760 pattern, not only for `Calling Off and On' but also for Opening and Closing generally.

Up to this point we have been dealing with facts; but on the specific questions as to why the Columns are raised and lowered, or why the care of the Lodge is the responsibility of the J.W. while the Brethren refresh themselves, we must resort to speculation.

In the operative system, c. 1400, when the Lodge was a workshop and before Lodge furniture was standardized, there was only one Warden. His duty was to keep the work going smoothly, to serve as a mediator in disputes and to see that `every brother had his due'. We have documentary evidence of this in the Regius and Cooke MSS of c. 1390 and c. 1410, and this idea apparently persisted into the Speculative system

THE FREEMASON AT WORK 23