Note: This material was scanned into text files for the sole purpose of convenient electronic research. This material is NOT intended as a reproduction of the original volumes. However close the material is to becoming a reproduced work, it should ONLY be regarded as a textual reference. Scanned at Phoenixmasonry by Ralph W. Omholt, PM in June 2007.

THE COLLECTED "PRESTONIAN LECTURES"

1961-1974

(Volume Two)

THE COLLECTED PRESTONIAN LECTURES

1961-1974

(Volume Two)

Edited by Harry Carr

LONDON

LEWIS Masonic

Quatuor Coronati Lodge

First published in collected form in England in 1965

by

Quatuor Coronati Lodge No 2076

This edition published in 1984 by

LEWIS MASONIC, Terminal House, Shepperton, Middlesex members of the

IAN ALLAN GROUP

Published by kind permission of

The Board of General Purposes of the United Grand Lodge of England

1. Freemasons. Quatuor Coronati Lodge 366'.1 HS395

ISBN 0-85318-132-2

Made and printed in Great Britain by The Garden City Press Limited Letchworth, Hertfordshire SG6 US

CONTENTS

List of Lecturers 1961-74 vi

List of Abbreviated References used in the text vi

Introduction by Cyril Batham vii

Year The Prestonian Lectures

1961 King Solomon in the Middle Ages Prof. G. Brett 1

1962 The Grand Mastership of

HRH the Duke of Sussex P. R. James 11

1963 Folklore into Masonry VRev H. G. Michael

Clarke 25

1964 The Genesis of Operative Masonry Rev A. J. Arkell 32

1965 Brethren who made Masonic

History E. Newton 46

1966 The Evolution of the English

Provincial Grand Lodge Hon W. R. S. Bathurst 58

1967 The Grand Lodge of England

- A History of the First

Hundred Years A. R. Hewitt 74

1968 The Five Noble Orders of

Architecture H. Kent Atkins 94

1969 External Influences on the

Evolution of English Masonry J. R. Clarke 106

1970 In the Beginning was the

Word ... Lt Col Eric Ward 117

1971 Masters and Master Masons Rev Canon R. Tydeman 133

1972 `It is not in the Power of any man:

A Study in change' T. O. Haunch 149

1973 In Search of Ritual Uniformity C. F. W. Dyer 168

1974 Drama and Craft N. Barker Cryer 196

Bibliography 242

vi

`THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES'

List of Illustrations

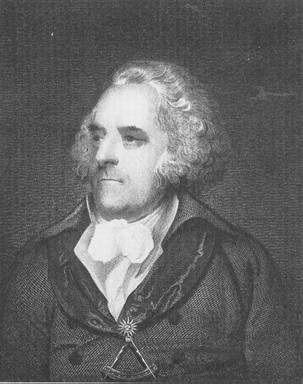

William Preston as PM of the Lodge of Antiquity Frontispiece

HRH Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex as MW Grand

Master of the United Grand Lodge of England, 1813-43 13

The Step Pyramid enclosure at Sakkara 35

Comparative Proportions of the Orders of Architecture 95

Solomon's Temple as visualised by Lt Col Eric Ward from available evidence 127

Solomon's Temple as imagined by the seventeenth-century artist,

Romain de Hooghe 128

The Battle of Rephidim as imagined by the sixteenth-century artist,

Philip Galle 131

The Lecturers

1961-74

W Bro Prof Gerard Brett, PM Felix Lodge No 1494.

W Bro P. R. James, MA, AKC, PAGDC.

RW Bro V Rev H. G. Michael Clarke, Prov GM Warwickshire. 1953-65.

W Bro Rev A. J. Arkell, MBE, MC, PM Old Bradford Lodge No 3549.

W Bro Edward Newton, PGStwd.

RW Bro Hon William R. S. Bathurst, TD, Prov GM Gloucestershire, 1950-70.

RW Bro A. R. Hewitt, FLA, PJGD.

W Bro H. K. Atkins, PAGSupt Wks.

W Bro J. R. Clarke, PJGD.

W Bro Lt Col Eric Ward, TD, PAGDC.

VW Bro Rev Canon R. Tydeman, PG Chaplain.

W Bro T. O. Haunch, MA, PAGSupt Wks.

W Bro C. F. W. Dyer, ERD, PJGD, AProv GM (West Kent).

W Bro Rev Neville Barker Cryer, PDepG Chaplain, A Prov GM (Surrey).

Abbreviated References used in the Text

AQC ‑ Ars Quatuor Coronatorum. Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge.

B of C‑ Book of Constitutions.

FQR ‑ Freemasons' Quarterly Review.

QCA ‑ Quatuor Coronatorum Antigrapha. Masonic Reprints of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge.

INTRODUCTION

EXTRACT FROM THE GRAND LODGE PROCEEDINGS FOR 5 DECEMBER 1923.

In the year 1818, Bro William Preston, a very active Freemason at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries, bequeathed ˙300 3 per cent. Consolidated Bank Annuities, the interest of which was to be applied `to some well‑informed Mason to deliver annually a Lecture on the First, Second, or Third Degree of the Order of Masonry according to the system practised in the Lodge of Antiquity' during his Mastership. For a number of years the terms of this bequest were acted upon, but for a long period no such Lecture has been delivered, and the Fund has gradually accumulated, and is now vested in the MW the Pro Grand Master, the Rt Hon Lord Ampthill, and W Bro Sir Kynaston Studd, PGD, as trustees. The Board has had under consideration for some period the desirability of framing a scheme which would enable the Fund to be used to the best advantage; and, in consultation with the Trustees who have given their assent, has now adopted such a scheme, which is given in full in Appendix A [See below], and will be put into operation when the sanction of Grand Lodge has been received.

The Grand Lodge sanction was duly given and the `scheme for the administration of the Prestonian fund' appeared in the Proceedings as follows:

APPENDIX

A SCHEME FOR ADMINISTRATION OF THE PRESTONIAN FUND

1. The Board of General Purposes shall be invited each year to nominate two Brethren of learning and responsibility from whom the Trustees shall appoint the Prestonian Lecturer for the year with power for the Board to subdelegate their power of nomination to the Library, Art, and Publications Committee of the Board, or such other Committee as they think fit.

2. The remuneration of the Lecturer so appointed shall be ˙5 5s Od for each Lecture delivered by him together with travelling expenses, if any, not exceeding ˙1 Ss Od, the number of Lectures delivered each year being determined by the income of the fund and the expenses incurred in the way of Lectures and administration.

3. The Lectures shall be delivered in accordance with the terms of the Trust.

One at least of the Lectures each year shall be delivered in London under the auspices of one or more London Lodges. The nomination of Lodges under whose auspices the Prestonian Lecture shall be delivered shall rest with the Trustees, but with power for one or more Lodges to prefer requests through the Grand Secretary for the Prestonian Lecture to vii viii `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' be delivered at a meeting of such Lodge or combined meeting of such Lodges.

4. Having regard to the fact that Bro William Preston was a member of the Lodge of Antiquity and the original Lectures were delivered under the aegis of that Lodge, it is suggested that the first nomination of a Lodge to arrange for the delivery of the Lecture shall be in favour of the Lodge of Antiquity should that Lodge so desire.

5. Lodges under whose auspices the Prestonian Lecture may be delivered shall be responsible for all the expenses attending the delivery of such Lecture except the Lecturer's Fee.

6. Requests for the delivery of the Prestonian Lecture in Provincial Lodges will be considered by the Trustee who may consult the Board as to the granting or refusal of such consent.

7. Requests from Provincial Lodges shall be made through Provincial Grand Secretaries to the Grand Secretary, and such requests, if granted, will be granted subject to the requesting Provinces making themselves responsible for the provision of a suitable hall in which the Lecture can be delivered, and for the Lecturer's travelling expenses beyond the sum of ˙1 5s Od, and if the Lecturer cannot reasonably get back to his place of abode on the same day, the requesting Province must pay his Hotel expenses or make other proper provision for his accommodation.

8. Provincial Grand Secretaries, in the case of Lectures delivered in the Province, and Secretaries of Lodges under whose auspices the Lecture may be delivered in London, shall report to the Trustees through the Grand Secretary the number in attendance at the Lecture, the manner in which the Lecture was received, and generally as to the proceedings thereat.

9. Master Masons, subscribing members of Lodges, may attend the Lectures, and a fee not exceeding 2s may be charged for their admission for the purpose of covering expenses.

Thus after a lapse of some sixty years the Prestonian Lectures were revived in their new form and, with the exception of the War period (1940‑46), a Prestonian Lecturer has been appointed by the Grand Lodge regularly each year.

It is interesting to see that neither of those two extracts announcing the revival of the Prestonian Lectures made any mention of the principal change that had been effected under the revival, a change that is here referred to as their new form. The importance of the new form is that the Lecturer is now permitted to choose his own subject and, apart from certain limitations inherent in the work, he really has a free choice.

Nowadays the official announcement of the appointment of the Prestonian Lecturer usually carries an additional paragraph which lends great weight to the appointment: The Board desires to emphasize the importance of these the only Lectures held under the authority of the Grand Lodge. It is, therefore, hoped that applications for the privilege of having one of these official Lectures will be made only by Lodges which are prepared to afford facilities INTRODUCTION for all Freemasons in their area, as well as their own members, to participate and thus ensure an attendance worthy of the occasion.

The Prestonian Lecturer has to deliver three `official' lectures to lodges applying for that honour. The `official' deliveries are usually allocated to one selected lodge in London and two in the provinces. In addition to these three the lecturer generally delivers the same lecture, unofficially, to other lodges all over the country, and, on occasions, to lodges abroad. It is customary for printed copies of the lecture to be sold‑in vast numbers‑for the benefit of one or more of the masonic charities selected by the author.

The Prestonian Lectures have the unique distinction, as noted above, that they are the only lectures given `with the authority of the Grand Lodge.' There are also two unusual financial aspects attaching to them. Firstly, that the lecturer is paid for his services, though the modest fee is not nearly as important as the honour of the appointment.

Secondly the lodges that are honoured with the official deliveries of the lectures are expected to take special measures for assembling a large audience and for that reason they are permitted ‑ on that occasion only ‑ to make a small nominal charge for admission.

In 1965 a collection of twenty‑seven Prestonian Lectures was published by Quatuor Coronati Lodge entitled The Collected Prestonian Lectures 1925‑60 and was edited by Harry Carr. Unfortunately this has long been out of print. It covered the period from the time of the revival of the lectures until 1960 with the exception of the following three lectures that were omitted because of their esoteric content: 1924 W Bro Capt C. W. Firebrace, The First Degree PGD 1932 W Bro J. Heron Lepper, The Evolution of Masonic PGD Ritual in England in the Eighteenth Century 1951 W Bro H. W. Chetwin, Variations in Masonic PAGDC Ceremonial Editorial versions of these three lectures were published by Quatuor Coronati Lodge in volume 94 of Ars Quatuor Coronatorum.

The present book contains the lectures from 1961 to 1974 and fortunately it has been possible to print all of them in full. They cover a wide range of masonic subjects and as all have been out of print for some considerable time, masonic students will certainly welcome this opportunity of obtaining a collected edition of them. Not only are they a valuable aid to masonic study but they are an excellent means of making `a daily advancement in masonic knowledge'.

There are only fourteen lectures in this collection, virtually one‑half of the number printed in the former volume but present‑day costs of book production have imposed this limit. It is hoped that in due course it will be possible to produce a third volume.

In some cases the lectures have been expanded or augmented in some way but in every such case this has been done by the individual lecturers. Further it must X `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' be emphasized that they and they alone are responsible for the opinions expressed and for the accuracy of the statements made. Most of those honoured by the United Grand Lodge of England in being appointed as Prestonian Lecturers had previously distinguished themselves, not only as masonic scholars, but in other aspects of masonic life and of the fourteen, no less than ten are or were members of Quatuor Coronati Lodge.

Finally it must be pointed out that not only this collection but also the individual lectures are copyright. In every case permission to publish these lectures has been obtained from the authors, their heirs or assigns and their help and co‑operation so freely given is gratefully acknowledged.

London, 1983. CYRIL N. BATHAM.

KING SOLOMON IN THE MIDDLE AGES THE PRESTONIAN LECTURE FOR 1961 GERARD BRETT THE PROBLEMS of continuity are among the most baffling of those which beset the historian. This is particularly the case in the history of Western Europe in the last 2,000 odd years. We are accustomed to think that of history within the framework invented for it by the German nineteenth‑century philosopher Friedrich Hegel as falling into three periods, the ancient, the medieval and the modern. A continuity between the ancient and the first part of the medieval period can often be traced, and so can one between the second half of the medieval and the modern. Continuity from the first period to the last, however, is extremely rare. Two outstanding examples of it will strike everyone at once ‑ the Christian church and the Latin language. Neither exists today in anything like the original form. As Miss Prism remarked to Canon Chasuble in Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest, `the primitive church has not survived in its original form'. In the same way, no one, with classical Latin in mind, has tried to master either of its chief modern derivatives, church Latin and Italian, will maintain that it has done so either. That there is continuity in each case, however, is quite clear.

Apart from these two, such examples as there are of this continuity are mainly to be found in the field of folklore, tradition and popular beliefs. It is with one of these that I want to deal today: the legend of King Solomon.

I cannot do better than to begin this lecture at the point where the research it incorporates began, that is, with a quotation from a sentence from a contribution to A QC, xxvii by Bro Chetwode Crawley: `Between the third and the thirteenth centuries,' he wrote, `there are not in the whole range of Western Literature a score of references to Solomon or to his Temple, and such as are known to exist are neither complimentary to the Wisdom of the King nor laudatory of the splendour of the edifice.' To my mind this contains two serious mistakes ‑ a misstatement of fact, in that medieval Western literature abounds with complimentary references to Solomon and his Temple, and a mistaken implication that none of the Temple legends existed in written form earlier than AD 1300. All the literature goes to show that Solomon was a great figure in the Middle Ages. In all this material there is, of course, the gap between the first and second Craft degrees on the one side and the third on the other. The origin of the Hiramic legend proper, as Bro Covey‑Crump has demonstrated, is unknown and possibly unknowable; there are no traces of it in medieval literature, and its absence where so much else is present is highly significant. The material in the first and second degrees, on the other hand, is mainly from the Old Testament, 1 2 `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' and, even when it is not, its origin is, I think, in every case traceable. But medieval literature, in revealing the transmission of this material, reveals also the recurring traditions about Solomon himself, his Temple, and his chief Architect; and I do not think anyone can study these traditions without beginning to wonder how old the legends may be in something at least nearly approaching the form in which we have them. The many legends about him fall under three headings: Solomon the magician, Solomon the wise man, Solomon the builder. Of these the third one seems to have been the main one from the start, and I propose to pass over the magician and the wise man stories rather rapidly here and concentrate my attention on Solomon the builder.

To begin then, with Solomon the magician. An implication that he was a magician is found in two passages in the Old Testament, while the latest writer on the subject points out that the evidence of Solomon's life, with its dark and disastrous end, were exactly of a kind to encourage such a legend. The legend had grown extensively by the time of Josephus in the first century AD. Here we find the legend's two commonest features ‑ Solomon's power over birds and animals, and the books he had written. It is made quite plain that the books referred to here were books of magic; and thus almost at the start we are introduced to the magical rituals which were to be a constant theme.

The aim of all magic is to acquire human control over non‑human agencies. Magic takes three great forms ‑ astrology, alchemy and ritual. Ritual magic, that is, the repetition of special words and formulae, is incidental to one if not both the other forms as well as to many types of organised religion. Its most important medieval use, and that in which it shows most clearly the aim of all magic, lies in demonology, the study and knowledge of demons with a view to their control for human purposes. It is in the Roman period, especially in the first four or five centuries AD, that we become aware of the full importance of demonology, principally for use in exorcism, that is the casting out of demons; a series of literary sources from the New Testament onwards shows the importance for the Christian as well as for the Jew of exorcism as a means of healing the sick.

Magical books ascribed to Solomon were widespread; Origen in the third century refers to the exorcistic formulae contained in them, and now for the first time we hear of the Seal of Solomon, which cast out demons because it contained the Holy Name of God ‑ an idea which appears in two passages in the Book of Revelation. Amulets of this period invoke Solomon's aid against a variety of ills: as the magician who knew all the demons by their names, and what ailments were caused by which, he was the obvious person to call on.

It is in the Testament of Solomon that the King's power and position appear most clearly; and the Testament, a Jewish work probably of the, fourth century AD, was to colour all European magical rituals for twelve hundred years. The Testament is hung on the thread of an autobiographical story of Solomon's life and reign, with stress on the building of the Temple. It is actually little more than a hand‑list of demons, giving their names, the mischief they cause, and how they are to be exorcised. The demonology is far more developed than any other feature of the work, and shows signs of various foreign influences, notably Egyptian and KING SOLOMON IN THE MIDDLE AGES Iranian, acting on its Jewish foundation. There are Christian influences, too; indeed, its importance partly lies in showing how close to each other Christianity and demonology were.

But the Testament has a wider importance. The first stage of demonology ‑ paramount in the Testament ‑ was a matter of exorcism and medicine. The next, which parts of the work foreshadow, was a change to demonology as a means of obtaining special benefits. To this end there was produced the series of manuals of demonology, which goes on into the sixteenth century, if not later. The most famous of these are the two Keys of Solomon; nearly all are attributed to him as a matter of course. It is here, perhaps, that it becomes most clear how great a figure Solomon the Magician was in the Middle Ages, and apart from the Manuals he reappears constantly in medieval literature. Most of the legends in the vast Solomon‑Magician corpus probably date from this time, and in any estimate of the mental atmosphere of the later Middle Ages he is a figure to reckon with. It was only with a further change in the character of demonology, and the rise of the new type of magician embodied in Faust, that Solomon lost ground.

The second strand in the tradition is that of Solomon the Wise Man. To a great extent, of course, the `Magician' element presupposes this, and in the earlier centuries the two are very hard to distinguish. In the earliest evidence, other than the Old Testament itself, Josephus mentions three points referable strictly to this idea‑ `books' Solomon had written (apart, that is, from the purely magical books already mentioned) ‑ a development from the generalised `Wisdom' which alone is attributed to him by the Old Testament; the riddles he exchanged with Hiram of Tyre, or his servant Abdemonus, which are the occasion for a disquisition on the wisdom of Solomon itself; and the Queen of Sheba's visit to test and hear his wisdom.

In the Christian centuries the idea of Solomon's wisdom seems to have gradually separated itself from that of his magic, and stress is increasingly laid on the idea of him as the receptory of the Divine Wisdom‑the Hagia Sophia itself; he appears in this light in at least one fresco with Biblical figures, a twelfth‑century example in S. Demetrius at Vladimir. There are glimpses of the idea of wisdom in general, both in the Testament and in other sources, in the ascription to him of all medical knowledge, indeed of the whole art of healing, without the implication of exorcism. The books appear again in the sixth century in Cosmas' `Solomon again wrote his own works, Proverbs, the Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes. For though he had received the gift of wisdom from God . . . he did not receive the gift of prophecy'; the riddling with Hiram and his servant, who here appears as Abdimus, in Jacques de Vitry's History of Jerusalem (thirteenth century). The Anglo‑Saxon Dialogue of Solomon and Saturn is a separate manifestation of this general idea; another, entirely separate and showing how widely prolific the idea was, is the Arab legend that the original strain of all Arab horses derives from the stallion Zad‑er‑Rakib, given by Solomon to an embassy of Azdites.

It is in the encyclopaedic age of the thirteenth century that the specific idea of Solomon as the repository of all Wisdom comes to its full flowering. The medieval notion of the Old and New Testament as complementary parts of one whole, the Old a prefiguration of the New, derives in its later form mainly from the THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' `Allegoriae quaedam Scripturae' of Isidore of Seville, though it is by no means original to him. It was not worked out in detail for some hundreds of years after Isidore, but when it was, we find Solomon as the symbol of Divine Wisdom, and as such the direct prefiguration of Christ Himself. This appears most clearly in the thirteenth century MSS of the Bible Moralises, where miniatures of the various events in the history of Solomon are accompanied by both the Old Testament text and a statement of the precise event in the life and ministry of Christ which is prefigured.

The same idea inspires the late medieval version of the story of the Queen of Sheba. The story is Biblical in origin, and appears in Josephus; but with the passage of time its character changes. In the earlier Middle Ages, as well as in Byzantine tradition throughout, the Queen speaks in dark language, and most resembles one of the Roman Sibyls, whereas Jewish and Aramaic writers see her essentially as the riddle giver. In twelfth‑century Europe, she was, so to speak, Christianised, and accepted into Western Christian legend, where she has remained ever since. Solomon is the Divine Wisdom; the Queen of Sheba is the Church coming from the ends of the earth to hear the words of Christ, as she appears in the twelfth‑century stained glass at Canterbury. Alternatively Solomon on the throne represents the Divine Wisdom on the knees of Mary, and the Queen of Sheba's visit, the Adoration of the Magi. The latter version is shown above the Central West Porch of Strasbourg Cathedral, in a relief carving of Solomon on the throne with the Virgin and Child above. The former is illustrated in the Bible Moralises, and in the series of pairs of sculptured figures at Amiens, Chartres, Reims and elsewhere, which were the subject of a fierce argument in AQCxix. The older Sibyl‑Prophetess idea did not die out completely: it reappears in the Nuremberg Liber Cronicarum of 1493; and on a German `Old Testament' Gothic tapestry of about 1500, are two figures with the names `Salaman' and `Sibilla'.

The other favourite scene of the wisdom of Solomon ‑ the Judgment ‑ has a longer specifically Christian history. What may be a caricature of it is on a Pompeian fresco (ie before the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79) in the Naples Museum; what is probably the earliest Christian representation is on the lid of a silver casket in the Church of San Nazaro in Milan, attributed to the late fourth century. There are other early medieval examples; and the judgment story, too, is drawn into the encyclopaedic explanation of the Bible. The Bible Moralises makes the living child prefigure the Church, the dead ‑ the Synagogue.

The first, or Magician element in the tradition seems to fade about the time of the Renaissance. Not, indeed, that the belief in magic itself fades then; it was, in fact, the great age of Alchemy, and the Philosopher's Stone was often taken to be identical with the Seal of Solomon. But Solomon as a Magician was dying with the Magician conceived as a heroic figure. Solomon as a Wise Man was by no means dead, and with the beginning of serious Old Testament study he takes on a new lease of life. The idea reaches its height, perhaps, in a story told by Bayle in his Dictionary; that Joshua Barnes, Cambridge Professor Greek, in 1710 wrote an epic poem of 10,000 lines to prove that Solomon was the author of the Iliad and Odyssey, attributed to Homer. It is only fair to add that Bayle admits a doubt KING SOLOMON IN THE MIDDLE AGES S whether this feat was not performed to please the Professor's wife, and so induce her to pay for his edition of Homer.

These two first strands in the Solomon tradition may at first sight appear to have little to do with the masonic legends, but I suggest that they are important, both as disposing of the suggestion that Solomon was an unknown figure in the Middle Ages and as giving a background to the Temple story. They provide evidence of those general ideas on Solomon which the Middle Ages had, and which the Temple legends do, in fact, presuppose.

For the Temple is the centre of the Solomon tradition from the start. In the Old Testament books it is already the main event; and as Solomon himself and the personalities of his reign passed first into memory and then into legend ‑ and especially after the first destruction of Jerusalem, as witness Psalm 137 ‑ the Temple became to an ever‑increasing degree the symbol of past ‑ and lost ‑ greatness. Josephus tells the whole story at great length, and comparison of his account with those of the Old Testament reveals the accretion of legendary and marvellous details to the original. In all later sources the influence of Josephus can be traced, occasionally with acknowledgement, more often not; `almost every person,' writes William of Malmesbury in the twelfth century, `is acquainted with what Josephus, Eucherius and Bede have said' (sc, about the Temple), and in the late medieval romance of 'Titus and Vespasian', Josephus is not only a main authority for the events, but appears as one of the chief actors in the drama.

Early Christian writers are, in the main, content to report the story much as Josephus tells it. Clement of Alexandria, in the Stromateis (second century), gives the story of Solomon's reign in some detail, opening with the statements that he reigned for forty years, and that Nathan the Prophet lived in his time and inspired the building of the Temple, of which Sadok was the first High Priest, being the eighth in the line from Aaron. Later come the marriage of Solomon to the daughter of Hiram of Tyre, at the time when Menelaus came to Phoenicia from Troy ‑ a good example of Clement's historical method of synthesising classical and Jewish history ‑ and the `Letters' of Solomon ‑ cited here from a lost work, Alexander on the Jews, and not from Josephus ‑ which brought him 80,000 workmen for the Temple from 'Hophra', King of Egypt, and another 80,000 from Hiram of Tyre, together with an architect named Hyperon, of a Jewish mother of the family of David; Eusebius, in the Praeparatio Evangelica (fourth century), tells much the same story, quoting the lost author Eupolemos, and adding a long description of the building, with particular reference to the two brass pillars gilded with pure gold. John Chrysostom devotes part of a sermon to an argument on whether its plan and design derived from Egypt, concluding in the negative. The Testament is contemporary with these, and, as its latest editor has pointed out, the Temple is the Leitmotif of the whole work ‑a good example of the essential unity of the three strands in the Solomon tradition: it is in order to build the Temple that Solomon seeks and acquires the power over demons which forms the real subject of the book.

With Gregory of Tours (sixth century) we are approaching the Middle Ages. Gregory mentions the Temple twice. In his History it is the subject of the sole reference to Solomon, and is described as of such magnificence and splendour 6 that the world has never seen its equal; in the de cursa Stellarum it is cited as one of the Seven Wonders of the World. In the lengthy de templo Solomonis of Bede (625‑735), we first meet the allegorical interpretation of the Temple story which has been a feature of the Western approach to it ever since; Bede, like Josephus, is a source on which many later writers draw. Bede states the basis of the allegorical approach in his first chapter: `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' His method is to start each section with the quotation of a sentence from the Old Testament describing some feature of the Temple, and to give a long allegorical explanation of it. Considerations of time and space make it impossible to cite examples; besides, much of it is intensely dull. Bede quotes some half‑adozen times from Josephus, and twice from Cassiodorus' Commentary on the Pslams; his own influence is clear to see in the three other most important medieval works on this class, Rhabanus Maurus' Commentary on the Books of Samuel and Kings (ninth century) ‑ a great deal of which is taken word for word from Bede‑Richard of Saint Victor's de Tavernaculo Tractatus Secundus (twelfth century), and the Historica Scholastica of Petrus Comestor (twelfth century). Of these, the first two give full importance to the allegorical approach of Bede; in the third it is much less to the fore. Comestor, whose work is an abridged and simplified Bible, is in general satisfied to tell a plain, but very detailed, story of the building and magnificence of the Temple; he relies mainly on the Old Testament and Josephus. Besides these writers, who are essentially ecclesiastical in approach, there are a number of others. Alcuin, for instance, refers to Charlemagne in the ninth century both as David and as Solomon, and, in reference to the new building, speaks of `that Temple of Aachen which is being constructed by the art of the most wise Solomon'. Both the Golden Legend (twelfth century) and Ranulf Higden's Polychronicon (fourteenth century) trace the whole history of Solomon, incorporating many of the later legendary additions, and Higden describes the Temple in considerable detail. From a far distant source‑Palestine itself ‑ comes a legend of unknown age, though it is medieval, to the effect that Solomon himself was a stonemason.

This mention of Palestine leads on to the third class of medieval sources on the Temple ‑ the tales brought back by the Pilgrims. The building they saw was, in fact, the Mosque of Omar, but by no means all of them appear to have realised that ‑ though as early as about AD 700 Bishop Arculf says firmly, `On the spot where the Temple once stood, near the Eastern gate, the Saracens have erected a house of prayer' ‑ and even some who do realise it write of the whole area as though the Temple were still standing. William of Malmesbury writes, `Here is the Church of Our Lord and the Temple which they call Solomon's, by whom built is unknown, but religiously reverenced by the Turks', and in the middle of the fifteenth century the Spanish traveller, Pero Tafur, `bargained with a renegade . . . and offered him two ducats if he would get me into the Temple of Solomon'.

The House of God, which King Solomon built in Jerusalem, was made in the model of the universal church, which from the first of the elect to the last who shall be born at the end of the world, is built daily by the grace of the peaceful King, her Redeamer.

KING SOLOMON IN THE MIDDLE AGES 7 The esteem in which the Temple was held is clear in all the pilgrim accounts. 'It exceeded all the mountains around in height,' writes Saewulf (AD 1102), 'and all walls and buildings in brilliancy and glory,' and 60 years later Benjamin of Tudela reported seeing the two great pillars, each with the name 'Solomon, son of David' engraved upon it, in the Church of S. Giovanni a Porta Latina in Rome. It is in line with these conceptions that in the rebuilding of Jerusalem after its capture by the Crusaders there was a 'Templum Domini', a 'Templum Salomonis' and a 'Domus Regia', and Jacques de Vitry writes: There is also at Jerusalem another temple of vast size and extent, after which the militant friars of the temple are called Templars. This is called Solomon's Temple, perhaps to distinguish it from the other, which is called the Lord's Temple.

The later period of the Temple literature was covered in Professor Swift Johnson's paper in A QC, xii; the facts he brings forward substantiate the theory of the permanence of western Temple traditions at this late period, and it would serve no purpose to cite them in detail here. It is interesting, however, to note the persistence of the tradition in Palestine, as shown, for instance, in the diary of Henry Maundrell, who went from Aleppo to Jerusalem and back in 1697, and refers to local legends of Solomon at Tyre (connected with the building of the Temple), Bethlehem and Jerusalem. The important point about almost all the later literature is the influence on it of the study of Ezekiel. This appears in both Richard of Saint‑Victor, who wrote a Commentary on Ezekiel's Temple, with accompanying plans, and Comestor; it led directly to the conclusion that the Temple of Solomon and the Temple described by Ezekiel were one and the same building. This is stated most explicitly late in the seventeenth century by the brothers Villalpandus; it is obviously present to the minds of many of the later writers, and to the makers of Temple models. Many of our own ideas of the magnificence of the building are probably to be traced back to it.

The Temple building appears more than any other feature of the Solomon tradition in works of art. It is, indeed, altogether absent during the first 12 Christian centuries in the West, but this absence is in line with the general dearth of Old Testament subjects at that time. Early in the thirteenth century, Solomon is shown kneeling and facing a Gothic building, with a pillared porch, in one of the quatrefoil panels by the south‑western door of Amiens Cathedral; he appears again, seated and watching the building of the Temple, in a Hamburg Bible of 1255 in the Royal Library at Copenhagen. It cannot be accidental that these earliest representations date from the didactic age of the Bible Moralisee, of Richard of Saint‑Victor, and of Comestor. The fourteenth century, so far as my researches have gone, is almost a blank period for Temple pictures, but with the fifteenth, and the generations following the first wave of vernacular translations of, and commentaries on, the Bible, figures of Solomon become ever more common, and we are able to see the importance attached to the Temple in the Solomon story of the time. The famous manuscript, Les Tres Riches Heures de Jean Duc de Berry, now in the Musee Conde at Chantilly, devotes a page to a scene similar to that in the Copenhagen Bible ‑ the Figure of Solomon facing a partially completed Temple. About the middle of the century this is again repe‑ 8 ated in the Josephus manuscript illustrated by the French miniaturist, Jean Foucquet, and now in the Bibliotheque Nationale; the Temple is here an exceedingly elaborate French Gothic building. The earlier English representations are figures in Tree of Jesse designs, with one exception ‑ the fourteenth‑century Queen Mary's Psalter. This has a series of illustrations of the history of Solomon, including the Temple building, a scene similar to that in the Copenhagen Bible. The development of the Tree of Jesse in medieval art is a very large subject, and it must be enough to say that the choice of figures in the earliest representations varies considerably. Solomon is by no means always one of them, and when he is present, he carries a plain sceptre. In later years he appears regularly as one of the ,standard' Ancestors of Christ, and at this time, too, the emblems carried by the figures come to be adapted more closely to the individual. David carries a harp, and Solomon either a sword of justice or a model Temple. Of the examples of the latter known to me, two are English and one Welsh, and the date of the earliest is also significant. This is the Jesse Window in Margaretting Church, in Essex, dated to about 1460; the others, also in glass, are at Thornhill, Yorkshire, dated 1499, and Llanrhaiadr, Denbighshire, dated 1533. The Margaretting temple is a Gothic building with a spire; of the other two, both taken from the artist Jean Pigonchet's illustrations to a French Book of Hours dated 1498, that at Thornhill is hexagonal, and that at Llanrhaiadr cruciform, with a tower and apparently a minaret. Another figure of Solomon is contemporary with Margaretting. It is a roof boss in the nave of Norwich Cathedral, carved under Bishop Lyhart, 1446‑72, and shows Solomon with a small Temple in the right hand and a sword in the left.

Another tradition is represented by Raphael's Fresco in the Vatican Stanza ‑ afterwards engraved and copied very widely ‑ a building scene with nothing in particular to distinguish the Temple, but with Solomon and othevfigures standing in the foreground. Going from the sublime to the ridiculous, a similar, but not certainly the same, scene is shown in a stained‑glass window of Flemish early sixteenth‑century origin, brought to this country from Rouen at the time of the French Revolution and erected in Prittlewell Church, Essex. It is one of a set of twelve, some of them copies from Durer, and shows masons at work on a building, watched by two overseers in the background; an angel carrying a square flies above them. The Temple itself, together with the Pillars, the sea of brass and the chariot with the urn, appears among a great variety of other scenes from the history of Solomon in the series of small books of Bible illustrations produced in many European countries during the sixteenth century, with designs by contemporary engravers. The general character of these illustrations is shown in that reproduced in A QC, lxi, 1, (opp p 132) from the Geneva Bible. With reference to the late Bro Poole's remarks, it may be mentioned that the idea of Bible illustrations of this kind and in this form appears first (to my knowledge) in a book published at Antwerp in 1528. The pillars, with their `bowls', appear in a separate illustration there, and in many others of the series, most of which seem to be contemporary with, or somewhat later than, the Geneva Bible. In the series as a whole we see the results of the earlier vernacular Bible versions. Later in the sixteenth and during the following century, a Temple building scene was commonly included in tapestry sets of the History of Solomon. The finest of these is `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' KING SOLOMON IN THE MIDDLE AGES 9 the Brussels tapestry in the Imperial Collections at Vienna; at least one English example is existant, an eighteenth‑century piece belonging to Lord Newton (Grand Lodge also possesses an example of the seventeenth century; it formerly belonged to Lord Charnwood and was acquired in c. 1952). It may be said of all these later Temple pictures that they bear out the substantial truth of Bro J. H. Rylands' dictum, that with the passage of time the Temple bears an everincreasing resemblance to a railway station hotel.

So much on the Temple generally; but before I conclude there are one or two points of special interest. The first concerns the two pillars. In the Greek translation of the Biblical manuscript known as the Septuagint, the two Hebrew names are transliterated as we know them today in Kings, but in Chronicles are rendered by the Greek words meaning 'strength' and 'right'. Josephus gives the Hebrew words only, and the early Christian writers, where they mention them at all, do so without translation. The Vulgate does the same, and it is only in comparatively modern editions of it ‑ the earliest I have been able to trace is the Paris edition of 1552 ‑ that a Glossary translates the words as 'In fortitudine aut in Hirco' ('in strength or' with a second meaningless word) and 'Praeparans sive praeparatio, vel firmitas' (preparing or preparation, or firmness).

The same Glossary, it is interesting to note, refers to a priest named J, of uncertain date, mentioned in I Chronicles ix, 10, and to a tribe of J.ites in Numbers xxvi, 12; the first of these appears to be the only ground for the legend attached to the name. Long before this, however, the significations almost as we have them had been attached to the pillars. Bede refers to them as 'J., that is, firmness', and 'B., that is, in strength', being followed word for word in this by both Rhabanus Maurus and Comestor. Medieval Jewish traditions about the pillars appear in Benjamin of Tudela, whose account of seeing them in Rome in 1160 has already been mentioned; and in the porch added to Wurzburg Cathedral by Bishop Hermann of Lobdeburg, between 1222 and 1254, the two main pillars at the entrance are carved respectively with the letters B. and J., to which the full names, both rather curiously spelled, have been added. That any of this carving is of the same date as the porch itself, is, I fear, unproven and unprovable. The Authorised Version of 1611 has 'In it is strength' and 'He shall establish', and the discrepancy between this and the older traditional signification of J. is interesting, considering the date.

Medieval sources have much to say about Hiram, though on the legend proper they are completely silent. The existence of two Hirams, implied in Kings and stated definitely in Chronicles, is accepted from the start, but there is some discrepancy between the accounts of Hiram the commoner's parentage, and even of his name; Clement calls him Hyperon. As to the name 'Abif', the introduction of which in Europe is generally attributed to Luther's Bible in the early sixteenth century, it is worthy of note that it is mentioned in Rhabanus Maurus' twelfthcentury Commentary of the Books of Chronicles. Hiram is mentioned as an architect rather than a bronzecaster by both Clement and Eusebius, both writing in the fourth century, but not by any of the later authors. The allegorical interpretation is stated most clearly by Bede, and in view of Bro Covey‑Crump's suggestion of a confusion between Hiram (sometimes spelled 'Iram') and Adonir‑ 10 `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' am, it may be said that the former is allegorised as the Teacher of the Church (the widow of the tribe of Israel) to the Gentiles, the latter, mentioned constantly as an overseer, as the Saviour Himself.

The medieval sources mention other points connected with Solomon and the Temple which there is no time to mention. One of them, after considering the legend that no metal tools were used to build the Temple, gives up the difficulty involved with the comment `it is no cause for wonder that in works of Solomon we find what can rather be marvelled at than usefully examined'. With this sentence we return to the basic conception of Solomon as a Wonder worker from which we started. I am aware that far from all the ground I have covered can be described as being immediately masonic research, if by that term is necessarily meant something connected with the Order we know today. My aim, within the restricted field I have tried to cover, has been to suggest a background of tradition and legend. I do not want to imply that all or much of this tradition ‑ if it was a tradition ‑ was, so to speak, masonic; but if, as the late Bro Knoop and his colleague stress in The Genesis, masonic tenets and principles are slow to grow, legends are even slower. Unlike tenets and principles, they are liable to change in their application; but even where this change may be suspected (and in no relevant case can it be proved), a useful purpose may be served by showing their age and development. Our knowledge of the extent of Old Testament learning at any given time before, say, the late fifteenth century is very incomplete. I believe myself that even the scanty material presented here justifies the phrase 'background of tradition' behind the particular form of many of our legends; and furthermore that though the gaps in time between the appearances of the various factors are sometimes long, it is more convincing to assume a tradition than an indefinite number of written sources, all repeating the same story and almost all now lost.

The vernacular translations of the Bible which begin in the later fourteenth century (in England with Wyclif), make the general tradition of Solomon, as then known, likely to be more popular than before. Their effect is to be traced in what may fairly be called the `Old Testament Revival', which has greatly affected the character of all the Reformed Churches, and in the growth of the iconography of Solomon. The medieval repertoire ‑ the Judgment, the visit of the Queen of Sheba, the various figures of the King, generally part of a Tree of Jesse ‑ is extended to include the Temple, the Idolatry, views of the Palace, Throne and details of buildings, and many small and fanciful scenes. But by the same token the effect of the vernacular Bible must have been to make the formation of entirely new legends, not directly dependent on the Old Testament, increasingly unlikely with the passage of time. The problem of the masonic legends is not how early their origin can be, but how late.

THE GRAND‑MASTERSHIP OF H.R.H. THE DUKE OF SUSSEX, 1813‑43 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURE FOR 1962 P. R. JAMES HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE DUKE OF SUSSEX was MW Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England from 1813 to 1843, during which period he exerted considerable influence upon the fortunes of the Craft. It is the purpose of this lecture to set forth the nature and extent of that influence. It is not intended as a biography,' but it is necessary first to know something of the man himself.

Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, sixth son and ninth child of George III and Queen Charlotte, was born in 1773. From early childhood he suffered from severe asthma, which sometimes incapacitated him for weeks at a time. It necessitated his living abroad until he was over thirty years of age and prevented him from adopting the customary military career. Educated in Hanover, his days were spent in travel and study whereby he acquired a well‑stocked mind and a famous library. A youthful and indiscreet marriage 2 cut him off from his father and the Court, while the Whig principles to which he steadfastly adhered alienated him from the Tory Governments of the day. Hence he never obtained any of those lucrative appointments which usually fell to members of the Royal Family and always suffered from pecuniary embarrassment. A good speaker and a good trencherman, his wide interests and liberal ideas made him a welcome chairman at many functions. For nine years he was President of the Royal Society and was also, at times, the head of several other learned bodies. 3 The Duke of Sussex's religious convictions have been the subject of much speculation. Undoubtedly he was very devout, spending upwards of two hours daily in the study of Holy Writ. In a letter published in The Christian Observer, May 1843, the Duke wrote that he was convinced of the divine origin of the Scriptures, `which contain matters beyond human understanding', and that he did not `concern himself with dogmas, which are of human origin. I am making this honest declaration,' he said, `not to be thought a Freethinker, which imputation I would indignantly repel; nor to pass for a person indifferent about religion.'4 His marginal comments in some of the theological works in his library show that his Christianity was unorthodox in that he opposed Creeds and held that the Scriptures must be reconciled to reasons He was a Modernist before his time. Among See Royal Dukes, Fulford, R.; AQC, Iii, pp 184‑224.

2 Royal Archives, Windsor Castle, Box File 'Augustus, D. of Sussex, 1786‑1842, No 48019'. 3 Gentleman's Magazine. N.S., vol six, pp 645‑652.

Some of the opinions of his late R. H. The Duke of Sussex on the subject of Religious Doctrine, by Richard Cogan, Esq; BT Mus, 4014 dd 6.

eg, The State in its Relation with the Church, W. E. Gladstone, 1838; Brit Mus, 1413 e 10; see also Cogan, loc cit.

12 `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' the Royal Archives at Windsor is a small manuscript book of prayers which formerly belonged to His Royal Highness. If he used it, and internal evidence goes to show that he did, it proves that he was a sincere and contrite believer in the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. His membership of Christian Orders whose obligations required such a belief confirms this. His religious opinions were, however, tolerant and, so far as Craft Masonry was concerned, `it was part of his masonic creed that, provided a man believe in the existence of the GAOTU and in futurity, and extends that belief likewise to a system of rewards and punishments hereafter, such a person is fully competent to be received as a brother'.' Masonically, he was a universalist.

The Duke of Sussex was initiated, 1798, in the Lodge Victorious Truth, Berlin, a constituent of the Royal York of Friendship, the Grand Lodge of Prussia, which then only accepted Christians. He passed through the several offices to the chair. On his return to England he was given the customary rank of Past GM, subsequently becoming DGM of the `Moderns', or Prince of Wales's, as they were then called. The Duke succeeded his brother, the Prince Regent, as Grand Master, 12 May 1813. He also joined, and for many years presided over, several other lodges, and he had a special fondness for the Pilgrim Lodge, No 238, which, like his Mother Lodge, worked its own ritual in the German language .2 `When I first determined,' he said, `to link myself with this noble Institution, it was a matter of very serious consideration with me; and I can assure the Brethren that it was at a period when, at least, I had the power of well considering the matter, for it was not in the boyish days of my youth, but at the more mature age of 25 or 26 years. I did not take it up as a light and trivial matter, but as a grave and serious concern of my life.'3 The immediate purpose of HRH becoming Grand Master of the `Moderns' was to bring about the long‑desired Union of the two Fraternities in England, upon which `his whole heart was bent'. For the same purpose his elder brother, the Duke of Kent, became Grand Master of the Atholl Masons, or `Ancients', and expressed similar sentiments .4 As a step towards the Union, the Lodge of Promulgation (1809‑11) was established to restore the Ancient Landmarks, to help `the Lodges of the Moderns fall into line with those of the Antients'.5 The Duke of Sussex, as RWM of the Lodge of Antiquity, No 1, was a member and made a useful contribution to the deliberations `by a luminous exposition of the Practices adhered to by our Masonic Brethren at Berlin'. 6 The ceremonies agreed upon, including that of a Board of Installed Masters, almost non‑existent among the Moderns, were rehearsed before the Duke, and arrangements made for their promulgation. The way was thus cleared for the Union, which was celebrated on 27 December 1813, the Duke of Sussex, on the proposition of the Duke of Kent, becoming MW Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of the United Grand Lodge of England. `This,' he said, `is the happiest event of my life' .7 Though t Loage of Research, Leicester. No 2429, Transactions. 1919‑20, p 97.

2 A Short History of the Pilgrim Lodge, No 238, F Bernhart, AQC. Ixvi. s Freemason's Quarterly Review. 1839, p 505.

Gould, History of Freemasonry, ed Poole, iii, p 81; A QC. Ixviii, p 49. 5 AQC, xxiii, p 215.

6 Lodge of Promulgation, Minutes, 29 December 1809; AQC. xxiii, p 38. 7 History of the Royal Alpha Lodge, No 16, Col Shadwell H. Clerke, p 5.

THE GRAND‑MASTERSHIP OF H.R.H. THE DUKE OF SUSSEX, 1813‑43 13 HRH Price Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex,.&c., &c., &c. MW Grand Master A print published in 1833. Now reproduced by kind permission of the Board of General Purposes, United Grand Lodge of England. The throne illustrated here is in the Grand Lodge Museum, and is used nowadays only at the Installation of a new Grand Master.

14 `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' others played notable parts, there is no doubt that the influence of the two Royal Grand Masters was paramount in bringing about the successful result.

To harmonise the ritual and ceremonies, the Lodge of Reconciliation was set up (1813‑16), the Grand Master sometimes attending its meetings. The chief obstacle was the Obligation in the First Degree.' Attention was drawn to it from the Chair and, having himself been obligated as an `Ancient' at his brother's Installation ,2 and possibly influenced by the judgment of the Swedish Ambassador to Spain at his own installation, 3 the Duke agreed to this Obligation being made more severe to meet the wishes of the Atholl Brethren. It having been settled, `the Ancient OBgn of the 1st and 2nd degrees were then repeated, the former from the Throne', both being approved by the Grand Lodge as `the only pure and genuine Obs. of these Degrees, and which all Lodges dependent on the Grand Lodge shall practice'. Notwithstanding this, and though the decisions of the Lodge of Reconciliation were finally approved by the Grand Lodge on 5 June 1816, they were not prescribed. Nor did the lodge consider the ceremony of a Board of Installed Masters. For this purpose the Duke of Sussex warranted a special lodge in 1827. With some exceptions the extended ceremony of Installation has fallen out of use: indeed, the Grand Secretary characterised it in 1889 as 'irregular'. 5 The Lectures, put into shape by William Preston, to whose beneficence we owe these Prestonian Lectures, were in those days almost as important as the ritual. Opinions differ as to what happened to them at the time of the Union. The Grand Master is said to have ordered that no alteration should be made in the Lectures, 6 and there is no mention of them in the records of the Lodges of Promulgation and Reconciliation. Yet some important changes were made in them about that time and the majority view is in favour of attributing these to Dr S. Hemmings, WM of the Lodge of Reconciliation, with other influences in the background. The most important change, and that which caused the greatest disturbance, was the substitution of Moses and Solomon for the two Saints John as the Two Great Parallels of Masonry. 7 In 1819 a complaint, endorsed by Peter Gilkes, was made to the Board of General Purposes that Bro Philip Broadfoot and the Lodge of Stability were working Lectures contrary to the stipulations of the Act of Union, they never having been in use in either branch of the Fraternity previous to the Union, and not having received any sanction from Grand Lodge. The complaint was rejected, but the Board decreed that no new Lecture could be used without the consent of the Grand Master or the Grand Lodge. The former laid it down that so long as the Master of any Lodge observed exactly the Land‑Marks of the Craft, he was at liberty to give the Lectures in the language best suited to the character of the Lodge over which he presided . . . that any Master of a Lodge, on visiting another Lodge, and approving of the Lectures delivered therein, is at Liberty to promulgate them from the Chair in his own Lodge, provided he has previously perfected himself in the Instructions of the Master of the aforesaid Lodge. The Grand Lodge concurring in the opinion thus ' A QC. xxiii, p 261.

Z Memorials of the Masonic Union, W. J. Hughan, ed J. T. Thorp, p 19. 3 A QC, Ivi, p 308.

GL Quarterly Communication, Minutes, 23 August 1815.

5 Dorset Masters Lodge, No 3366, Transactions, 1928‑29, pp 19‑23; Misc. Lat., NS, ii, pp 123‑6. 6 FQR, 1843, p 46.

' Gould, ed Poole, iii, 108; AQC, xxiii, pp 260, 274; xli, pp 191, 197‑201; Misc. Lat., NS, vi, pp 114‑16, 129‑132.

THE GRAND‑MASTERSHIP OF H.R.H. THE DUKE OF SUSSEX, 1813‑43 15 delivered by the MW the Grand Master, requested His Royal Highness to permit the same to stand recorded in the minutes of the day's proceedings, to which HRH acceded.' The process of de‑Christianising the Craft ritual and ceremonies, gradual since 1717,2 was now completed. In place of the two Festivals kept by the Ancients on the two St John's Days, there was to be, under Article XIV of the Union, `A Masonic Festival, annually, on the Anniversary of the Feast of St John the Baptist, or of St George, or such other day as the Grand Master shall appoint'. The General Regulations then adopted and the Book of Constitutions settled for `the Wednesday following the great national festival of St George'. 3 The structure remains Christian, but nearly every Christian allusion has been eliminated in favour of universality. Whose was the influence remains a moot point; in any case, the responsibility was that of the Grand Master. 4 The `new method' was not received with unanimous approval. Both sides felt that they had surrendered something vital, and there was bitter rivalry among lodges and individual brethren. The Union was carried through in the last stages of the Napoleonic War and was worked out during its aftermath of distress and discontent, complicated by the upheaval of the Industrial Revolution. For a generation the country was torn by numerous more or less violent agitations which provoked the Government into repressive legislation or reluctant concessions. Such conditions were not conducive to masonic progress and the number of lodges declined. When the Duke of Sussex ascended the throne there were some 650 of them; when he died there were fewer than 500. In 1828 fifty‑nine lodges were erased for not having made returns for a considerable time; no new lodges were warranted in London between 1813 and 1839.5 The new Grand Master, who was resolved, unlike his predecessors, to rule as well as to reign, realised that a firm hand was necessary. `I recommend to you,' he said, `order, regularity and the observance of masonic duties.'6 Not unnaturally, there was some opposition.

From his own Lodge of Antiquity there came, in 1814, an Address to him as its RW Master, drawn up by Charles Bonnor, who had been the Acting Master and had done much useful work in the Lodge of Promulgation. It complained, in ,exceedingly objectionable, offensive and slanderous terms', that the Duke had not done his duty by the lodge in allowing it to lose some of its privileges at the Union, especially that of being No 1 on the roll. His Royal Highness referred the complaint to the lodge, when the opposition to Bonnor, led by William Meyrick, Grand Registrar, presented a counter Address expressing complete confidence in their RW Master, and expelled Bonnor from the lodge. For printing his Address, Bonnor was charged before the Board of General Purposes and expelled from Grand Lodge, though he was soon reinstated. Two years later he fell into disgrace again and was deprived of his Grand Rank. At the same time, in Grand Lodge, Bro Robert Leslie, jun, RWM of Lodge No 9, used some disrespectful remarks to I' GL Quarterly Communication, Minutes, 1 September, 1 December 1819; History of the Emulation Lodge of mprovement, H. Sadler, pp 109‑12.

Lodge of Research, Leicester, No 2429, Transactions, 1906‑7, pp 39‑40. 3 Memorials of the Masonic Union, W. J. Hughan, ed J. T. Thorp, p 76.

The Symbol of Glory, Dr G. Oliver (1850), pp xvii, 20, 51, 78; FQR, 1844,0 36, 1845, pp 409‑11; A Commentary on the Frrmasonic Ritual, E. H. Cartwright, pp 10, 14, 92; AQC, xlv, p 93.

AQC, Ixviii, pp 129‑31; Dorset Masters Lodge, No 3366, Transactions, 1918, p 112; Illustrations of Masonry, W. Prgston, 14th Edn, p 418.

FQR Supplementary No 1843, p 193.

16 `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' the Grand Master in the Chair, `a proceeding of unexampled outrage tending to create discord and dissentions in the Grand Lodge, to undermine the principles on which the late happy Union of the two Grand Lodges of Masons in England was established and insulting to the Grand Lodge in the person of the MW the Grand Master'. The Board decided that his offence merited expulsion, but owing to his youth and inexperience, and the apology he had offered, he was let off with a year's suspension.' Also in this same year, 1814, a group of Ancient Lodges in London formed an influential committee, led by Bro J. H. Goldsworthy, which circulated resolutions against the `Innovations', saying that the Lodge of Reconciliation had ,altered all the ceremonies and language of masonry and had not left one sentence standing'. 2 They were particularly opposed to the Obligations. The Lodge of Reconciliation expelled Goldsworthy from its membership and, calling the dissenters before it, made some slight variations to meet their wishes. They were not satisfied, refused to hold intercourse with the United Grand Lodge and proposed the formation of a new Lodge of Reconciliation. Gradually their resistance broke down, and by 1816 they had more or less grudgingly adopted the system of working officially set forth.

There was no harmony in Bath, either. There, the three Modern lodges, Royal Cumberland, No 55 (now 41), Virtue, No 311, and Royal York of Perfect Friendship, No 243, combined to build a new Masonic Hall, opened by HRH the Duke of Sussex with full ceremony in 1819. The project soon failed, partly from lack of co‑operation from the one Ancient lodge in the city, the Royal Sussex, No 61 (now 53), the first to be named after the Duke, by his special permission .4 Rivalry developed into bitterness, the Moderns refusing visits from the Royal Sussex Lodge. Internal disputes shook all four and the Board of General Purposes was called in to adjudicate. As a result, the Royal York Lodge was erased in 1824 and the Lodge of Virtue in 1839, the remaining two continuing their hostilities for many years. On one occasion a member of the Royal Sussex ran off with the warrant of the Knight Templar Encampment attached to the Royal Cumberland Lodge, thus bringing its activities to a temporary close. 5 From Sussex to Lancashire, from Ipswich to Bristol, came reports of unrest. Brethren resigned or were expelled, lodges were suspended or erased through opposition to the new order. It must not be thought, however, that the revolt, though widespread, was general. More ink has been spilled over a few sinners than over the 'ninety‑and‑nine' which needed no repentance. The great majority either loyally accepted the new working or, unheading, quietly continued their old ways. Uniformity in the ceremonies is neither practicable nor desirable.

The best‑known and possibly the most resistance led to the foundation of a rival Grand Lodge at Wigan. 6 In Lancashire, Ancients and Moderns had long worked t GL Quarterly Communication, Minutes, 1 June 1814, to 4 December 1816; Records of the Lodge of Antiquity, No 2, vol it, Capt C. W. Firebrace, 26 January to 20 February 1814.

2 Statement by the WM. Phoenix Lodge, No 289, to the L of Reconciliation. 3 AQC, xxiii, pp 233‑51.

Autograph letter, dated December 1813, in GL Library.

s From the records of Lodges 41 and 53; Somerset Masters Lodge. No 3746, Transactions, 1925. pp 400‑61; 1958, pp 29Tb311.

History of the Wigan Grand Lodge, E. B. Beesley, 1920; The Grand Lodge in Wigan, N. Rogers, A QC, lxi, pp 170‑210.

THE GRAND‑MASTERSHIP OF H.R.H. THE DUKE OF SUSSEX, 1813‑43 17 in harmony and continued to do so after the Union, but there was discontent caused by the introduction of a Provincial Grand Master and the innovations of the Lodge of Reconciliation. The revolt began in 1818 with a threat to close a lodge because of its few members. Then a Memorial was sent from the Provincial Grand Lodge to the Grand Master, who pigeon‑holed it because it contained matter concerning the Royal Arch and was therefore outside the scope of the Board of General Purposes. The Brethren of Lodge No 31, Liverpool, thereupon charged the Board, who knew nothing about it, with suppressing the Memorial, `a dangerous innovation', and circulated the document to all lodges. For this, 68 (later reduced to 26) brethren were expelled from the Craft and the lodge erased. Others who supported Lodge No 31 soon suffered the same fate. The PG Master was suspended `with a view to remove prejudice and suspicion', William Meyrick, Grand Registrar, being placed in charge of the Province. When the PGM died in 1825, the Grand Master divided it into two Provinces. The penalties imposed were severe but necessary; they compare favourably with those of the Government in dealing with the contemporary affair at `Peterloo'. The erased lodges and their supporters continued to meet and, at a meeting in Liverpool, 27 December 1823, resolved to restore the Ancient Grand Lodge on the grounds that the new (1815) Book of Constitutions established a dangerous and despotic authority, that the Landmarks of the Order had not been maintained, and that, as many lodges and individual masons had seceded from it, the United Grand Lodge had ceased to exist. Seven lodges joined the new body, whose headquarters were in the Lodge of Sincerity, which became No 1. The Wigan Grand Lodge functioned formally for many years, only ceasing to exist when the Lodge of Sincerity rejoined the fold in 1913.

Cases such as these were generally referred by the Grand Master to the Board of General Purposes, but his influence was usually, though not always, predominant. The process was probably much the same as had been used in the Moderns Grand Lodge before the Union, described by the Swedish Ambassador to Spain: `The Duke was seated on an elevated throne in the East, in front of a great table around which thirty‑five persons were seated. Here all cases concerning Freemasonry were decided . . . The laws were read, and then the Secretary read out a number of cases. At each of them the Chairman said: "A motion is made and seconded. Who approves will raise his right hand." In most cases all present shouted "All", but one question took a long time: it concerned a Master who had been drunk several times in Lodge and behaved in a disorderly way, and whom the Duke wished removed. But there were persons who defended him and also others of opinin not only that he ought to be removed, but also deprived of the dignity of a Brother. There was an awful row. They spoke with a certain amount of heat, but many quite well, and the Duke had to put the proposition eleven times before it was accepted by the majority." Considerable authority was vested in the MW Grand Master by the new Book of Constitutions. His own annual election, proposed from the floor of Grand Lodge from 1836,2 was purely formal. He appointed all the Grand Officers, the ' 1 December 1813; AQC, Ivi, pp 129‑30. 2 FQR, 1836, p 399.

18 `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' Grand Chaplain, Sword Bearer and, for a time, the Grand Treasurer, being selected from three brethren nominated by the Grand Lodge.' He also chose nearly half the members of the Boards through which that body exercised its administrative functions. The Duke's appointments to Grand Rank have met with some criticism. He said: `Merit is the sole means of promotion',2 and that he had `never given any Brother office who was not in other respects eligible to enter Grand Lodge'. 3 The appointments for 1837 were said to have honestly represented the various interests of the Craft and to `prove that the "Eye" of the Grand Master is observant of merit, and that it does not limit its range of vision to this or that Lodge' .4 Yet three years earlier, when the Grand Master's sight was failing, it was alleged that there had been `a kindly yielding to the solicitations of private friendship', and therefore the appointments were `not altogether gratifying to the expectations of the Craft'.5 Three days after the Union the Duke offered the Deputy Grand‑Mastership to the dissolute and unwashed Duke of Norfolk, who had once been PGM for Herefordshire. 6 The SGW of 1838, Lord Worsley, had been raised only a few days before his appointment, 7 and the Grand Registrar, appointed to that very important office at a critical time in 1840, was seventy years of age and had only four years' experience as a Freemason. 8 Gould wrote that `The Duke of Sussex was, in his way, a despot . . . his patronage was not confined to the right (from 1819) of nominating all the Grand Officers, except the Treasurer. He altered at pleasure the status of any Grand Officer, created new offices, and freely appointed Brethren to rank in Grand Lodge'.9 He may have asked a Brother at a Quarterly Communication to fill a casual vacancy through absence, but an analysis of his appointments from 1813 to 1843 shows that Gould's assertion is not true. The Wardens and Deacons were changed annually, the Sword Bearer almost so; the other officers continued for several years and there was no abnormal creation of new offices. During the whole period there were less than a dozen promotions and, although he was at loggerheads with him at the time, he made Dr R. T. Crucefix Junior Grand Deacon in 1836.

The Duke of Sussex was prone to act on his initiative and to interfere personally in proceedings, though he denied any intention of dictation.'░ He conferred privileges upon those lodges in which he was specially interested." He decided that a Serving Brother could only become a subscribing member in a lodge other than that in which he was initiated under dispensation, but he was not disposed to do anything further in the case of a lodge which has initiated two serving brethren and an excessive number of candidates after being refused a dispensation, because he thought they had acted under a misapprehension. 12 The disputes in Bristol and in the Silent Temple Lodge, No 126, Burnley, 13 were GL Quarterly Communications, Minutes. 7 September 1814, 6 March 1816, etc. Z FQR, 1836, p 319, note.

3 FQR, 1840, p 498. FQR, 1837, pp 293‑4. 5 FQR, 1834, pp 240‑1.

6 AQC, Iii, p 208, 214, 216; Complete Peerage (Doubleday). 7 FQR, 1840, p 285.

s Lodge of Research, Leicester, No 2429, Transactions, 1919‑20, p 96. 9 Gould, ed Poole, iii, 110.

░AQC. Iii, p 112 I eg, 'itch race, op c1L p 155.

~z GL Quarterly Communications, Minutes, 5 March 1834. ~3 Communicated by W Bro N. Rogers.

THE GRAND‑MASTERSHIP OF H.R.H. THE DUKE OF SUSSEX, 1813‑43 19 both smoothed over by the Grand Master's personal intervention. On the other hand, whilst the case of the PGM for Somerset against Thomas Whitney, of the Royal York Lodge of Bath, was sub judice, the Duke wrote that the latter's statements were `as distant from truth as the East is from the West', and he told the Board of General Purposes that they were not to receive any affidavits during the course of their investigation. `As Masons,' he said, `we rule and judge by the laws of Conscience and Honour. Public Opinion and the strict observance of a Mason's Word are our only means of Control . . . we cannot punish legally for perjury'.' In 1834 the Duke ordered that there should be no professional singers in the Glee Room with the ladies at the Boys' Festival because of an unpleasant incident three years before. This had a bad effect on contributions to the Institution, so he withdrew the restriction in 1836.2 The Grand Master of England worked in cordial co‑operation with the Duke of Leinster, head of the Order in Ireland, but on one occasion he over‑reached himself and was severely snubbed. Freemasonry in Ireland was made illegal in 1823, and the PGM for Upper Canada attempted to compel an Irish lodge there to accept an English warrant. In 1826 the papers were laid before the Duke of Sussex, who suggested to the Grand Master of Ireland that Irish lodges overseas should be placed under the Grand Lodge of England for better control. The Irish Grand Lodge would thus abandon its rights under the International Compact of 1814. They reacted strongly, characterising the Duke of Sussex's conduct as unmasonic, and issued a new warrant to their lodge in Canada. 3 It was said by the DG Master, Lord Durham, himself in 1835 that `until lately the proceedings at the Quarterly Communications were mere promulgations and registrations of the edicts of the Grand Master; but, Brethren, there has arisen of late a spirit of enquiry worthy of our glorious profession, that has found its way into our legislative assembly, that has brought about discussions upon most important subjects and this has been happily marked by an especial propriety of conduct, and the exercise of great intellectual powers. I have sincere pleasure in stating my conviction that the Grand Master, so far from viewing these proceedings with either distrust or jealousy, is gratified to know that they have taken place. '4 Bro Philipe, a member of the Board of General Purposes, added that the Grand Master `during the past year had, in a most especial manner, endeared himself to the Craft by the ready and kind manner in which he had met their wishes upon some important changes'. 5 At this period, however, the Duke was absent from Grand Lodge owing to his blindness. When he recovered, after an operation, there was a change for the worse.

The Duke was a `persevering and unwearied patron of every charitable institution, the most charming beggar in Europe'. 6 In 1829 he approved the design of a jewel to be worn by brethren who had served as stewards to both the Masonic Charities, the Boys' and the Girls' Institutions. It was his concern for these that involved him in the worst dispute of his reign. Dr R. T. Crucefix, in 1834, ' Autograph letter dated 24 October 1824, in GL Library. 2 FQR, 1834, pp 49‑51. 159‑61, 240, 419; 1836, p 169.

3 History of the Grand Lodge of F. and A. Masons of Ireland, R. E. Parkinson (1957), pp 60‑67. 4 FQR, 1835, p 176.

5 Ibid, p 432.

6 FQR, 1843, p 141; A QC, Ixvi, p 71.

20 `THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES' suggested the erection of an Asylum for Aged and Decayed Freemasons, inviting the Duke to become its president. But the Grand Master opposed the scheme on the grounds that the proceedings of Dr Crucefix and his supporters were irregular, that it would induce improper persons to enter the Fraternity, and that it would adversely affect the two existing Charities ‑ the Girls' School being at that time in financial difficulties. Interviews between the Duke and Crucefix were variously interpreted, the latter saying that the Grand Master was 'not opposed' to the Asylum, whilst the former said he was,' though he changed his grounds. `Finding that opposition but aided the Asylum, [he] adopted the plan of competition and hoisted the standard of a Masonic Benevolent Annuity Fund. The Duke of Sussex for a long time denied his patronage, but Walton2 sought an interview with him and, meeting with a repulse on his favourite theme, he fairly told the Grand Master, on taking leave, that there remained no other means of preventing the Asylum being built and endowed. This decided the matter; the Grand Master relaxed, adopted Walton's scheme and thus proved the fallacy of all opposition to the Asylum principle; which, so far from being uncalled for and unnecessary, became the parent of a second Masonic Charity." Crucefix, fortified by a Grand Lodge resolution unanimously in favour of the Asylum, went on with his scheme and managed it as though it was an official business with governors, collections, festivals, and so on. A dispute at a meeting held 3 November 1839, led to Crucefix and his lieutenant, J. Lee Stevens, being temporarily suspended from their masonic duties. Crucefix's appeal against the sentence being disallowed, he wrote a highly improper letter to the Duke of Sussex, accusing him of disregarding the Ancient Charges, and recalling a memorable scene in the Grand Secretary's office on 29 April 1840, when the Grand Master `threatened me with the enforcement of a power beyond the Masonic Law and expressed that threat in language so unusual and unexpected from a Brother of your exalted Rank and Station, as was calculated to lower the respect due to the person of Your Royal Highness, and above all the dignified Office of Grand Master'. 5 This the Duke ignored until it was published in Crucefix's periodical, The Freemason's Quarterly Review. Now, publication of masonic proceedings was anathema to the Grand Master. Charles Bonnor, of the Lodge of Antiquity, No 2, and the brethren of Lodge No 31, Liverpool, had been penalised for such an offence. Also, Laurence Thompson, a Prestonian Lecturer and one of Crucefix's opponents, fell under the Grand Master's displeasure for publishing a form of ceremonial promoted by the Lodge of Reconciliation, of which he was a member. 6 Earlier in this same year, 1840, the Duke had circularised all lodges warning them against printing masonic information. The appearance of Crucefix's letter in the Review, therefore, caused the Grand Master to lay it before the Board of General Purposes, `leaving to their Discretion the Proceed AQC, Iii, p 199‑200: FQR, 1837, pp 484‑5.

2 Isaac Walton, PM of the Moira Lodge, No 92. 3 Gould, ed Poole, iii, 109‑10.

FQR, 1838, flyleaf.