Many Fraternal Groups Grew From

Masonic Seed

(Part 1 -- 1730-1860)

by

Barbara FrancoIn 1831, when the young Frenchman Alexis de Touqueville, toured the United States, he already noted a national characteristic for forming organizations. "Americans of all ages, all conditions, in all dispositions," he tells us, "constantly form associations."

..If it is proposed to inculcate some truth or to foster some feeling by the encouragement of a great example, they form a society."

Toqueville was fascinated by the American experiment with democracy and suspected a close relationship between the voluntary associations he observed and the system of democratic government. In "Democracy in America", he states:

Thus the most democratic country on the face of the year is that in which men have, in our time, carried to the highest perfection the act of pursuing in common the object to their common desires and have applied this new science to the greatest number of purposes. Is this the result of accident, or is there in reality any necessary connection between the principle of association and that of equality.

An astute observer, Toqueville recognized that associations played an important role in American society of the 1830's. From volunteer fire companies to temperance organizations, from historical societies to college fraternities, Americans have continued to form associations to accomplish common goals and to share common experiences. Among thousands of organizations, none have been more responsive to changing needs and concerns than the large number of fraternal societies that date from the 18th century to the present offering members fellowship, mutual aid, self improvement, and shared values.

Since it opened in 1975, the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum of our National Heritage has been collecting artifacts and written materials dealing with the history of Freemasonry and other fraternal organizations. Although the museum's main focus remains American history, a panel of museum directors and prominent historians who convened for a planning symposium in 1978 urged the museum to concentrate its collections and research on the subject of fraternal organizations in America. They felt that the subject was important and one that had been neglected by museums and scholars.

The research and collecting that has taken place over the past ten years has confirmed Toqueville's opinion that "nothing...is more deserving, attention than the intellectual and moral associations of America.... In the democratic countries the science of association is the mother of science; the Progress of all the rest depends upon the progress it has made."

At the time of Toqueville's visit, fraternal organizations were already a 100-year-old tradition in America. Beginning in the 1730's with the establishment of lodges of Freemasons in Philadelphia and Boston, fraternal organizations took root and prospered on Americans soil. Many with transplanted from Europe, others developed here, but all patterned themselves after Freemasonry to include ritual, regalia, and secret passwords. A variety of aims characterize these organizations – co-operative insurance, social or political change, patriotism, protection of labor interests, and personal virtue, and public abstinence.

From Masonic lodges to Grange halls, all fraternal organizations share basic similarities. Rituals and degrees borrow exotic titles and dramatic scenarios from ancient legends, historical incidents, or mythology. Bonds of secrecy held establish solidarity among members. Regalia provides fantasy and drama; the lodge provides fellowship; and death and sickness benefits offered a sense of security prior to Social Security, pension plans, and medical and life insurance.

Freemasonry, the earliest the fraternal organizations established in America was transported from England in the 1730's as a philosophical society associated with the liberal ideas of the Enlightenment, yet steeped in the ancient tradition of the stonemasons' guilds. Early lodges in America and England met in taverns or private homes. Good fellowship and strong spirits often accompanied the philosophical discussions of new ideas while the rituals were designed to educate and improve moral virtues. The symbols of Freemasonry were drawn from a wide variety of 18th-century sources that included stonemasons' tools, classical architecture, the beehive of industry, the anchor of hope, mourning symbols, and heraldry.

An account book of a Philadelphia Lodge, dated June 24, 1731, is the earliest lived in record of an American Lodge, although earlier accounts of the British Masonic items in America suggest that Americans were familiar with Freemasonry before 1731. American lodges were chartered by the Grand Lodge of England established 1717, the Grand Lodge of Ireland established 1729, or the Grand Lodge of Scotland, 1736.

Freemasonry in America grew rapidly and played an important role in the social and political history of the country. Meeting in public taverns, 18th-century Masonic lodges provided a vehicle for the popularization and spread of new ideas that included the equality of man, the power of reason over dogma, and the existence of natural laws. These radical ideas eventually formed the basis for American arguments favoring political separation from Great Britain.

During the Revolutionary Period, Freemasonry served as a unifying influence. Relations among the American colonies had often been characterized by jealousies, territorial disputes, and widely diverse ethnic, social and religious groups. By 1775, Masonic lodges established in each the 13 colonies served as a common denominator to help bring the divergent groups within the colonies into a single national entity. At least nine of the signers of the Declaration of Independence and many of the military leaders of the Revolution were Freemasons. George Washington's Masonic affiliation was an important ingredient in his role as military and political leader of the new nation.

Masonic ties and patriotism were so closely entwined during this period that theyvirtually merge in popular usage. The ideas of equality, reasons, and brotherhood of man, inherent in Freemasonry, had been translated into American independent and democracy.

In searching for a style that would represent the newly formed United States, American craftsmen, many of whom were members of the fraternity, quite naturally turned to the well-known system of symbols that Freemasonry provided.

In America, the most widespread use of these emblems as decoration dates from the last quarter of the 18th-century and continues through the 1830's. So many of the individuals involved in the Revolution were Freemasons the Masonic imagery, often combined patriotic symbols, can be found on almost every type of decorated object used in America and can truly be considered a national style that went beyond the exclusive use of the fraternity of Freemasons. The most dramatic example is probably the use of the all seeing Eye and pyramid on the Great Seal the United States, but Federal style furniture, clocks, anglo-American ceramics, Chinese Export porcelains, glassware's, and textiles, as well as specific Lodge furnishings and regalia also attest to the prominence of these symbols in the 18th and 19th-century America.

In addition to remaining one of the most popular fraternal organizations in America from the 18th century to the present, Freemasonry has also served as a model for the many other organizations that proliferated in the 19th century. Following the pattern set by Freemasonry, other American fraternal groups developed a similar didactic style using symbols to teach democratic principles and personal virtues in a changing American society, much as Freemasonry taught its own moral system. Because Freemasons were often involved in establishing new fraternal orders, many incorporated Masonic symbols in their own rituals. Thus the square and compasses, beehive, hour-glass, and clasped hands appear among the symbols of many organizations.

While the earliest fraternal artifacts are almost exclusively Masonic, by the 19th century other groups joined Freemasonry with similar types of decoration and artifacts. The 19th century provides a chronology of fraternal organizations whose foundings parallel important developments in American social and cultural history.

Odd Fellowship originated the England as early as 1745. Similar to Freemasonry, it has degrees and symbols and teaches moral lessons in its ritual. Thomas Wildey and other English Odd Fellows who emigrated to America organized the Independent Order of Odd Fellows beginning with a Lodge in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1819. The main symbols of the order are the three links representing Friendship, Love and Truth; clasped hands, and heart in hand.

The Odd Fellows differed from Freemasonry by offering a more specific beneficiary program in which members systematically contributed to a fund from which sick or distressed members, their widow, and orphans could be paid.

By the end of the 19th-century, in part due to its insurance aspects, Odd Fellowship equaled or even outstripped Freemasonry in membership. Many men belonged to both organizations. The large membership of Odd Fellows in the mid-19th century is supported by the number of interesting decorative arts pieces with the symbols of the organization that are found from this period. The three links, the heart in hand, and clasped hands of Odd Fellowship became almost as prevalent as the square and compasses.

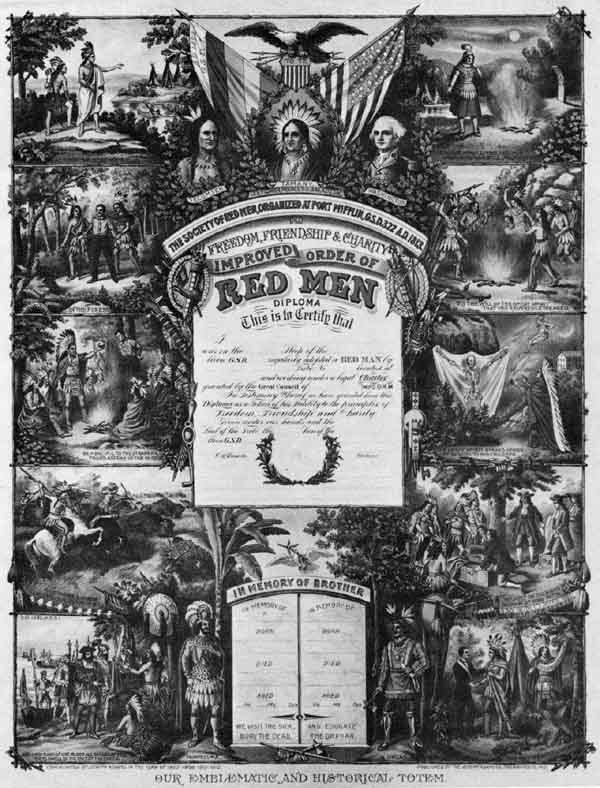

The 1830's marked a new period of growth for fraternal organizations in America. The Ancient Order of Foresters, based on the legends of Robin Hood, was established in America in 1832, followed in 1834 by the Improved Order of Red Men, which drew its inspiration from American Indian legend. In 1835, the United Ancient Order of Druids, which based its ritual of the Druid traditions and legends, was established in America from England. All of these organization were modeled on the lines of Odd Fellowship, offering mutual benefit in the event of sickness and death in addition to fraternal rituals and social contract.

The 1830's and 1840's marked the first of the 19th century waves of immigrants from Europe, and fraternal orders developed in response to these new Americans. In 1820's, fewer than 6,000 Germans and 54,000 Irish emigrated to America. In each of the next two decades, those figures jumped to 125,000 and 385,000 German immigrants and 207,000 and 790,000 Irish immigrants.. The Ancient Order of Hibernians in America, established in New York in 1836, was devoted to paying relief and death benefits, the advancement of the Roman Catholic religion, and promotion of Irish national traditions. Similarly, the Order of the Sons of Hermann, established 1840, and the German Order of the Harugari in 1847 were both founded in response to the ethnic prejudice directed against recent German immigrants.

Fraternal organizations played a particularly important role among German-Jewish immigrants. Traditional Jewish life had centered around the synagogue and the village. In America these institutions with disrupted by assimilation, religious reform, and cultural differences among Sephardic and German Jews. Jewish relief societies first operated under the auspices of individual synagogues, but often found their efforts fragmented.

In the 1840's secular fraternal orders developed: B'nai B'rith in 1843, the Free Sons of Israel in 1846, and the United Order of True Sisters in 1849. These organizations provided a way for Jews of various nationalities and sects to help each other while maintaining their Jewish identity.

Writing in 1878, Charles Wesolowsky, a Freemason and a member of B'nai B'rith wrote that "Thanks to Providence B'B Lodge is now the supplement, and no matter where you are, the same work, the same sign, the same spirit, you are at home and amongst brothers indeed." The rites, regalia, and mottoes of these organizations, based on Freemasonry and Odd Fellowship, offered at American aura that might be denied Jews elsewhere.

Wessolowsky offers an interesting example of how a German-Jewish immigrant in the 19th century viewed fraternal organizations in America. On his tombstone he wanted the inscription to include his Masonic achievement, "Past Grand High Priest of Georgia" because it demonstrated "the extent to which an immigrant Jew living in America could enter into brotherhood with his Gentile neighbours and still retain his identity as a Jew and pride in his Jewish heritage."

At the same time that increasing numbers of immigrants were creating their own fraternal orders to help adapt to their new American Identity, many native-born Americans began to fear that these new arrivals would corrupt American traditions and take jobs away from them.

The order of United American Mechanics, founded in Philadelphia in 1845, became the first of the Nativist fraternal organizations. Its objectives were to be patriotic, social and benevolent fraternal order composed of native white male citizens who would help native-born Americans find employment, protect the public school system, and aid the widows and orphans of members. It specifically opposed the immigration of large numbers of German and Irish Roman Catholics in the 1840's. The organization's emblem incorporated the Masonic square and compasses with the arm of labor wielding a hammer and the American flag.

The Junior Order of United American Mechanics, founded in 1853, became a separate society sharing the same Nativist concerns.

Probably the best known of the Nativist fraternal organizations of this period is the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, better known as the "Know-Nothings." Members would reply that they "ken nothing" when asked about the new secret political group. Drawing from its support from the members of other fraternal organizations with Nativist sentiments such as the United American Mechanics and the Brotherhood of the Union, the Know-Nothings won surprising political victories in elections following its founding in 1852. By 1856, the group was restructured as a non-secret, national political organization throughout the 1850's and only lost strength in the 1860's when the Civil War overshadowed concerns about immigration.

Nativism was not the only burning issue of the 1840's that found expressing in fraternal organizations. In 1842 the Sons of Temperance organized in New York as a fraternal benefit society and same year the Independent Order of Rechabites was brought to the United States from England as a secret fraternal and total abstinence society. From these organizations a number of groups developed such as the independent Order of Good Templars and the Templars of Honor and Temperance. Organized in 1850, the Independent Order of Good Templars offered no insurance benefits and was one of the first fraternal organizations to admit both men and women.

The issue of women's rights was voiced at the First Women's Rights Convention have the Seneca Falls, N.Y., in 1848. The emerging role of women in America can be seen in the fraternal organizations of this period. Increasingly organizations like the Odd Fellows felt they needed to explain why women were not included. An Odd fellows Monitor and Guide for 1878, for example, explains that "Lodges of Odd Fellows are formed, and in them men are banded together to do what is natural for women to do. The leading principles of our Order are but the innate principles of women's nature."

In fact, the Odd Fellows became one of the first men's fraternal organizations to establish a degree for women with the Daughters of Rebekah founded in 1851. Freemasonry followed in 1857 with the Order of the Eastern Star.

If some organizations argued that women did not need fraternal organizations, others felt that they needed women. According to Rosswell Hassam's Readings and Recittions for Good Templar Lodges published in 1880, the independent Order of Good Templars proudly proclaimed the reasons for the success by including that "the Order was fortunate in at once calling to its aid the wonderful help a woman. No similar institution had ever taken the ste before..."

Jewish women, in particular, used organizations to play a more prominent role in community affairs. The United Order of True Sisters, founded by Henrietta in 1846, was modeled after the Independent Order of B'nai B'rith and became the first women's fraternal and philanthropic organization in the United States.

Even before the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation, the status of free blacks came into question in relation to American fraternal organizations. Mirroring the status of blacks in America society, most fraternal organizations simply excluded black members. Prince Hall, a free black clergyman serving a congregation in Cambridge, Mass., was one of 15 black men initiated into Freemasonry on March 6, 1775, in a British Army lodge whose members were stationed in Boston. Hall then formed a Masonic Lodge of black man, subsequently receiving a charter from the Grand Lodge of England when he was unable to obtain one from the Provincial Grand Lodge of Massachusetts. Hall went on to fight in the American Revolution at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Prince Hall Freemasonry proceeded to form its own Grand Lodges and higher degrees and has remained an important part of the American black community.

Similarly, Peter Ogden, a black sailor initiated into Odd Fellowship in England, founded the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows when the American Independent Order of Odd Fellows would not grant a charter because the signers were of African descent. Ogden instead requested a charter through his own lodge in Liverpool, England.

Households of Ruth, a black women's group based of the Biblical story of Ruth and Naomi, was started in 1856.

Representing nearly every ethnic group, religion, and race, and both sexes, fraternal organizations played a critical role in the emergence of American pluralism from the late 1700's to the Civil War. Freemasonry helped popularize the Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. Most fraternal organizations taught the secular democratic virtues of friendship, unity, loyalty, charity and education.

The "Odd Fellows Text Book" in 1851 states that Odd Fellowship is "genuine republicanism" because "in the disposition of its government and the bestowment of its bounties and honors, the people, the members bear the rule and share equal and undisputed rights."

Fraternal organizations helped to assimilate immigrants into America society by reinforcing democratic values in their rituals and by practicing democratic rule in their organizational bylaws. They also offered stability through periods of social and political change – whether in the years of uncertainty following the American Revolution, or the turmoil of the Civil War.

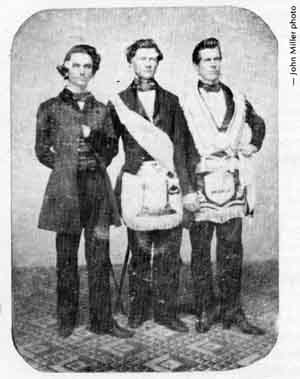

This 1850 daguerreotype from the museum's collection shows three men wearing black suits with one wearing a Masonic apron and another wearing Odd Fellows regalia.

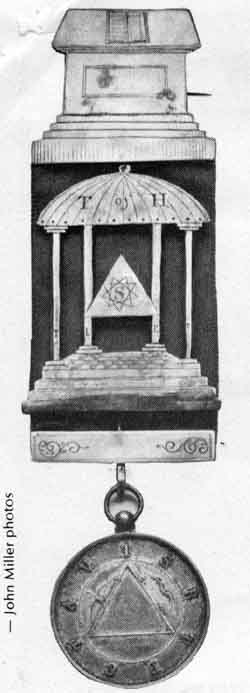

Jewel of the Templars of Honor and Temperance, founded in 1846.

This 19th-century painted tin sign with symbols of the Junior Order of United American Mechanics was probably used on a lodge building. symbols of the order include a shield, arm and hammer, and square and compasses.

Diploma of Improved Order of Red Men

Sextant case carved with a variety of Odd Fellows symbols

Extracted from:

The Northern Lights

This is the first of a two-part series outlining the role of fraternal organizations in America and their relationship to Freemasonry. Barbara Franco has provided us with the results of her research while she was preparing for the museum's 10th anniversary exhibit, "Fraternally Yours: A Decade of Collecting." Part 2, covering the period from 1860-1920, will appear in the November issue.

September 1985

Published by

Supreme Council, 33rd Degree

Ancient & Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry

Northern Masonic Jurisdiction

United States of America

PO Box 519

Lexington, Mass. 02173

(Pages 4-8)=== ==== ==== ==== ==== ====

1999-11-01