This is a complex question; on one level, it

is true that we can learn all that the ritual book teaches without such visual

aids. On another level however, the tracing boards contain clues; clues about

aspects of the teachings of the three degrees that are not evident in the

words of today’s printed ritual.

We have to remember that the printing of clear text rituals is a fairly modern

practice. There are signs that in the days when the ritual had to be learned

from an oral tradition, much more was imparted to the student. This is the

only way we can explain why, for instance, the Grand Principles on which

masonry is founded, Brotherly Love, Relief and Truth, are only communicated to

the Entered Apprentice when he learns the questions leading from the first to

the second degree – they are mentioned nowhere at all in the first degree.

Similarly, two of the richest stores of

masonic allegory, the five noble orders of architecture and the seven liberal

arts and sciences, are spoken of only to point out two sets of steps in a

stairway, one of five and one of seven. These crucially important allegorical

tokens are nowhere fully expounded, unless you read the Emulation lectures.

Yet if we examine, for instance, some of the American tracing boards of the

eighteenth century we find intricate drawings of the orders of architecture,

which make it clear that the Master, or another mason charged with instructing

younger Brethren, must have gone to great lengths to delve into the intricate

differences and significations of the five orders.

In London, 1762, an exposé of Freemasonry entitled Jachin and Boaz was

published in which the following passage appears:

He [the candidate] is also learnt the Step, or how to advance to the Master upon the Drawing on the Floor, which in some Lodges resembles the grand Building, termed a Mosaic Palace, and is described with the utmost Exactness. They also draw other Figures, one of which is called the Laced Tuft, and the other the Throne beset with Stars …

The author adds,

In some Lodges, the new-made Member is obliged to take a Mop out of a Pail of Water, and wash the Drawing on the Floor out, which puts him in some Confusion, and creates great Mirth among Brethren.

In other words, they were exceedingly

careful that the images they drew on the floor of the lodge should not be seen

by the profane world.

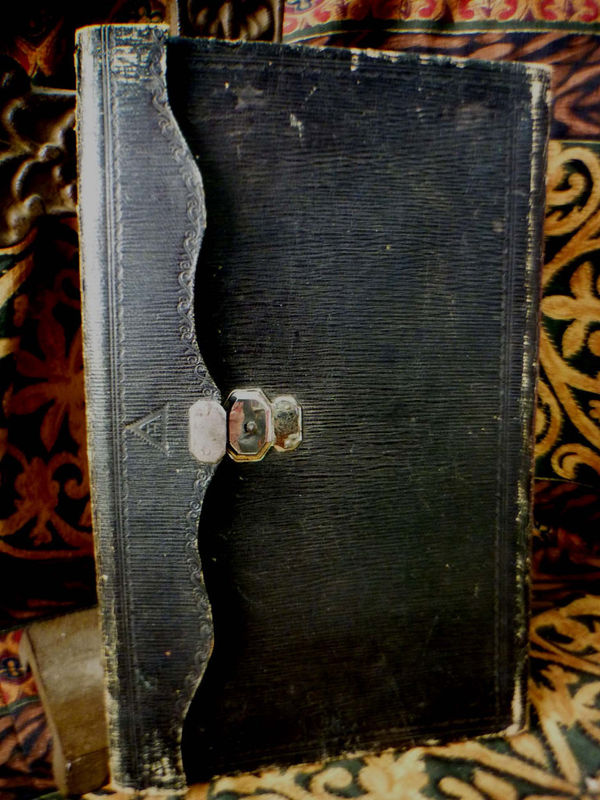

From the middle of the eighteenth century in England the designs were being

reproduced on floor-cloths, as it was becoming too laborious to wash away the

design every time the lodge was closed. These practices were being copied on

the continent, in France, Germany and Austria in the form of lodge cloths or

carpets. A later exposure showing a French lodge at work was reproduced in an

engraving, showing the Brethren ranged on either side of a floor cloth with

symbols depicted on it.

Later still, the cloths were supported on a board or on trestles and from this followed the practice of executing the design on a rigid, framed board. According to Terry Haunch in his paper for the Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge, No. 2076 there is some evidence that the term ‘trestle board,’ ‘trassle board’ and other variants became corrupted into ‘traising board’ and later ‘tracing board’. In the United States the term ‘trestle board’ is still used for this object.

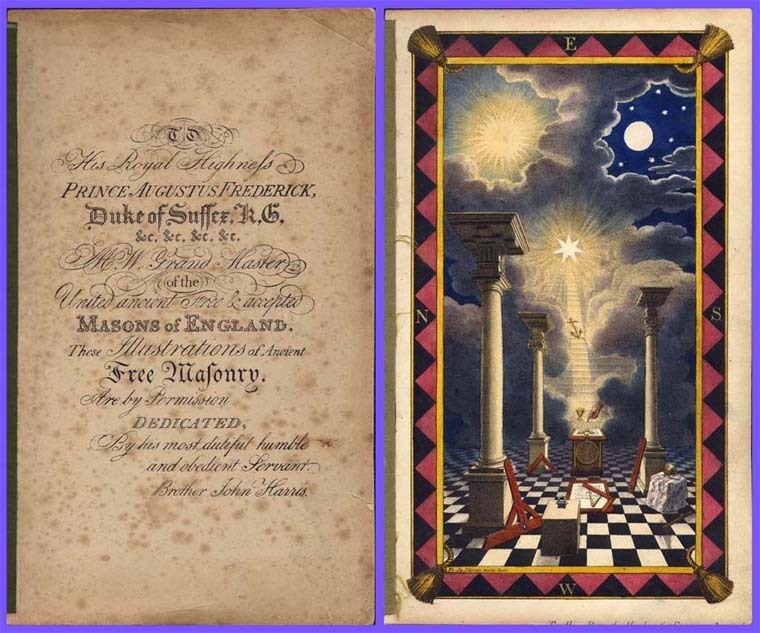

Very few boards dating from before 1800 have survived, but after that year the names of certain English designers come to the fore, including John Cole, whose engravings appeared in 1801, and John Browne, the author of the famous Master Key (1798), who designed a set of boards in full colour in about 1800.

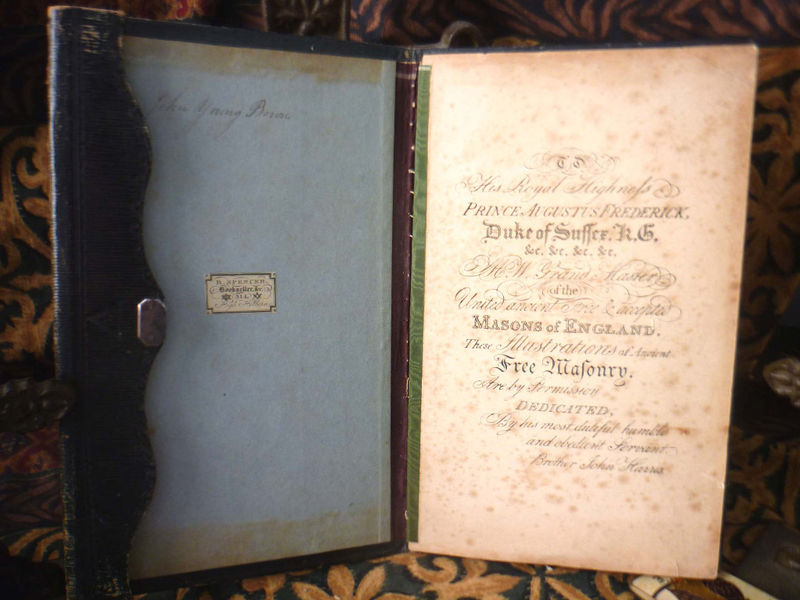

With the advent of boards designed by Josiah Bowring, a portrait painter, we see an attempt to produce aesthetically pleasing boards, employing perspective, and to include more detail than his predecessors. Bowring’s boards certainly raised the standard of those who came after him. Of these, by far the most accomplished was John Harris, whose prolific output leaves us sets of boards designed in 1820, 1825, 1845 and 1849. It was Harris’ boards of 1845 which won for him a competition launched by the Emulation Lodge of Improvement in that year. These boards, 6 by 3 feet in size, are still in use by the lodge today.

Continental European lodges often have lodge

carpets rather than rigid boards. Pilgrim Lodge, No. 238, in London, which has

worked in the German language since 1779, uses such a carpet. Since the

reestablishment of Freemasonry in countries previously under communism, lodges

have been busy designing carpets in the twenty-first century idiom leading to

a flowering of Masonic art. We see lodge carpets woven in Germany with vibrant

colours and attention to detail which have pushed out the boundaries of the

eighteenth and nineteenth century designs we are used to in England. We see

boards designed by the Hungarian artist Ferec Sebök in which a form of Art

Deco becomes transmuted in an almost surreal manner.

In the United States tracing boards are no longer used except in those lodges

working English rituals, but there are some splendid examples of very

elaborate and intricate painted boards and cloths which are now mostly the

property of museums.

Freemasonry, after all, is about rendering in symbol and allegory that which

words alone cannot express. And a visual image gives us a way of using our own

insight to de-code the message. The tracing boards are there to do just that –

from their original function of laying out the plan of the building, they have

developed into a means for us to lay out the message, and then to profit by

it.

With acknowledgment to Terence O. Haunch, former

Director of the Library and Museum of Freemasonry, London, author of Tracing

Boards – their Development and their Designers.