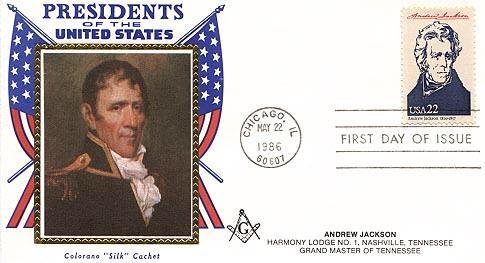

Andrew

Jackson

Seventh

President of the United States

More nearly than any of his

predecessors, Andrew Jackson was elected by popular vote; as President he

sought to act as the direct representative of the common man. Born in a

backwoods settlement in the Carolinas in 1767, he received sporadic

education. But in his late teens he read law for about two years, and he

became an outstanding young lawyer in Tennessee. Fiercely jealous of his

honor, he engaged in brawls, and in a duel killed a man who cast an

unjustified slur on his wife Rachel.

Jackson prospered sufficiently to buy slaves and to build a mansion, the

Hermitage, near Nashville. He was the first man elected from Tennessee to the

House of Representatives, and he served briefly in the Senate. A major

general in the War of 1812, Jackson became a national hero when he defeated

the British at New Orleans.

In 1824 some state political factions rallied around Jackson; by 1828 enough

had joined "Old Hickory" to win numerous state elections and control

of the Federal administration in Washington. In his first Annual Message

to Congress, Jackson recommended eliminating the Electoral College. He also

tried to democratize Federal office holding. Already state machines were

being built on patronage, and a New York Senator openly proclaimed "that

to the victors belong the spoils. . . . " Jackson took a milder view.

Decrying officeholders who seemed to enjoy life tenure, he believed Government

duties could be "so plain and simple" that offices should rotate

among deserving applicants. As national politics polarized around

Jackson and his opposition, two parties grew out of the old Republican

Party--the Democratic Republicans, or Democrats, adhering to Jackson; and the

National Republicans, or Whigs, opposing him. Henry Clay, Daniel

Webster, and other Whig leaders proclaimed themselves defenders of popular

liberties against the usurpation of Jackson. Hostile cartoonists

portrayed him as King Andrew I. Behind their accusations lay the fact

that Jackson, unlike previous Presidents, did not defer to Congress in

policy-making but used his power of the veto and his party leadership to

assume command. The greatest party battle centered around the Second

Bank of the United States, a private corporation but virtually a

Government-sponsored monopoly. When Jackson appeared hostile toward it, the

Bank threw its power against him. Clay and Webster, who had acted as

attorneys for the Bank, led the fight for its recharter in Congress. "The

bank," Jackson told Martin Van Buren, "is trying to kill me, but

I will kill it!" Jackson, in vetoing the recharter bill, charged the

Bank with undue economic privilege. His views won approval from the

American electorate; in 1832 he polled more than 56 percent of the popular

vote and almost five times as many electoral votes as Clay. Jackson met

head-on the challenge of John C. Calhoun, leader of forces trying to rid

themselves of a high protective tariff. When South Carolina undertook to

nullify the tariff, Jackson ordered armed forces to Charleston and privately

threatened to hang Calhoun. Violence seemed imminent until Clay

negotiated a compromise: tariffs were lowered and South Carolina dropped

nullification. In January of 1832, while the President was dining with

friends at the White House, someone whispered to him that the Senate had

rejected the nomination of Martin Van Buren as Minister to England.

Jackson jumped to his feet and exclaimed, "By the Eternal! I'll smash

them!" So he did. His favorite, Van Buren, became Vice President, and

succeeded to the Presidency when "Old Hickory" retired to the

Hermitage, where he died in June 1845.