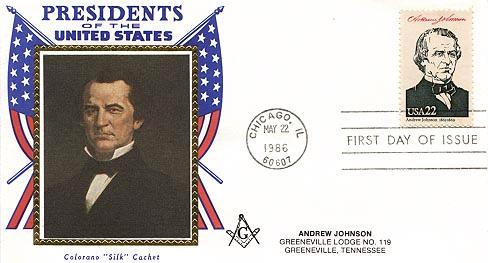

Andrew

Johnson

Seventeenth

President of the United States

Johnson was born on Dec. 29,

1808, in Raleigh, N. C., the younger of two sons. His father was a porter who

died in 1811 after saving a man from drowning. His mother supported the family

by spinning and weaving cloth in their Raleigh cottage. At the age of 14,

Johnson was apprenticed to a tailor.

Already showing signs of the ambition that drove him all his life, Johnson

learned the basics of reading and writing from the foreman of his shop and

trained himself as a public speaker. By the time he was 16, Johnson was

restless and dissatisfied with the limits his apprenticeship placed on his

life. In 1827 he moved with his family, finally settling in Greeneville, in

the eastern Tennessee hill country, where he opened his own tailor shop. In

the same year he married Eliza McCardle, who furthered his education and

helped him prosper in his business. In Greeneville, Johnson's personal

magnetism, native ability, and powerful will made him a leader of the town's

younger skilled artisans. In the social ferment of the late 1820's and early

1830's, when Andrew Jackson and his advisers both capitalized on and promoted

a new spirit of egalitarianism, Johnson and his friends were inspired to try

to replace the town's traditional political leaders. In 1829, Johnson and

several other artisans were elected to the Greeneville town council, and in

1831 he was elected mayor. Attracted by the anti-aristocratic rhetoric of

Jackson and his political intimates, Johnson and his friends allied with

hundreds of likeminded budding political organizations to form the new

Democratic Party.

The spirit of democracy meshed well with Johnson's own resentments and

ambitions. Poor in his youth and still a tailor without pretensions of social

rank, he stressed the egalitarian, anti-aristocratic strain of Jacksonian

democracy, as well as its distrust of government at all levels. An active,

powerful government, insisted Johnson and other radical Jacksonians, was

subject to manipulation by the rich and powerful. He maintained that the

Constitution should be construed strictly and opposed national government

encroachments on "states' rights." But unlike many Democrats, he

urged that similar principles be applied to the state governments. This led

him into conflict with the western Tennessee Democratic leaders--slaveholders

who dominated the party.

Johnson was elected to the state legislature in 1835, 1839, and 1841, and to

the U.S. Congress in 1843. He expressed his constitutional principles by

voting consistently against the tariff, internal improvements, higher salaries

for government employees, or any other "extravagance." Gerrymandered

out of Congress in 1852 by a Whig legislature, he won the Democratic

nomination for governor in 1853, finally gaining control of the party from his

Tennessee opponents. He barely defeated the Whig candidate and served two

terms from 1853 to 1857, when he was elected to the U.S. Senate.

Although Johnson himself owned a few slaves and loyally defended slavery and

"states' rights," his relations with proslavery Democratic leaders

were strained. Within the framework of Tennessee state politics, Johnson was

the spokesman of the nonslaveholding interests of the state. In the Senate his

most treasured proposal was the Homestead Bill, a measure that would have

given 160 acres (65 ha) of western land to anyone who would settle on and

cultivate it for five years. Such a program would have precluded the large

plantations associated with slavery. Southern congressmen opposed it bitterly,

while the new, antislavery Republican party of the North favored it.

These tensions were exacerbated in 1860, when Johnson cooperated with

Tennessee Democrats who favored Stephen A. Douglas for the presidency. Douglas

had alienated most Southern Democrats by refusing to endorse their right to

take slaves anywhere in the western territories. But Johnson himself had

slight commitment to the expansion of slavery there, and he hoped that he

would get Douglas's support as a compromise presidential candidate if he and

his enemies fought to a stalemate. When the struggle led to the division of

the Democratic party, Johnson supported the pro-Southern nominee, John C.

Breckinridge. His dalliance with Douglas, however, had already injured him

with most Southern Democrats.

Johnson's association with the Democrats ended completely when he worked to

prevent Tennessee from joining the secession movement after Lincoln's election

in 1860. Allying with pro-Union Whigs, for several months he fought old

Democratic enemies to a standstill. But when war came, western and central

Tennessee voted overwhelmingly to join the South. Only eastern Tennessee held

out, and Johnson with it--the only Southern senator to refuse to go with his

state. Johnson's position, which forced him and his family to flee Tennessee,

made him a hero in the North. In Congress he came into close contact with

Republicans and pro-war Democrats, now cooperating in the so-called Union

party. When Union forces gained control of central Tennessee in 1862, Lincoln

appointed Johnson military governor.

Lincoln hoped that Johnson would be able to create a new civilian government

loyal to the Union, but the attempt met with scant success. The few Unionists

were badly divided between those who hoped to retain slavery and conciliate

pro-Confederates and those who wished to abolish slavery and punish traitors.

Johnson took a position in between. While he urged bold steps to restore civil

government, both groups held back, convinced that most Tennesseans would not

cooperate until Confederate troops still in the state were crushed, which did

not occur until December 1864. Within three months Tennesseans held a

convention, framed a new state constitution, and elected a new governor and

congressman.

As Lincoln's running mate on the Union party ticket, Johnson was elected in

November 1864. Ill at the time of the inauguration in March 1865, Johnson made

the mistake of fortifying himself with whiskey before the ceremonies. His

inaugural address was rambling and almost incoherent. The humiliating

experience--made doubly painful by his chronic insecurity--lent apparent

substance to rumors of alcoholism that plagued him for the rest of his life.

The wound was just beginning to heal when, on April 15, 1865, Johnson became

president after Lincoln's assassination.

As soon as he became president, Johnson faced the

knottiest problem of the post-Civil War era--formulating a policy for

restoring the Union. Difficult for Lincoln, this task was even harder for

Johnson. Lincoln was a Northerner with an intimate knowledge of Northern

attitudes toward slavery, race, and the South, as well as with the sentiments

and necessities of the Union party. He shared the mixed feelings of racism and

humanitarian concern for ex-slaves that characterized most Northerners, as

well as their conflicting desires for a quick return to normality and for

fundamental changes that would guarantee the security of the Union. Johnson,

on the other hand, was a Southerner. Toward blacks he displayed alternately a

sympathetic paternalism and a contemptuous hostility. He understood the

politics of the South better than any Northern Republican, but he had no real

feeling for the North, and he was especially ignorant of the balance of forces

in the Union party.

A strict constructionist who believed in limited government, Johnson found

federal domination of the people of the South extremely distasteful.

Determined to reestablish state governments in the South as quickly as

possible, he decided to follow a modified version of the program that Lincoln

had developed during the war. This provided for the speedy framing of new

state constitutions abolishing slavery and the election of new state officers.

He also added requirements that the new states ratify the 13th Amendment,

repudiate Confederate debts, and nullify secession ordinances. All this was to

be done under the temporary wartime authority of the president as commander in

chief of the armed forces. When the states met his conditions, he would

recognize their restoration to the Union, and the war would be officially

over. Southerners met his conditions quickly. When Congress met in December

1865, he thought the job was almost complete.

To a Southern Unionist the plan seemed excellent, but it revealed Johnson's

ignorance of the sentiments of most Northerners. Johnson's program left the

decision of how to cope with emancipation completely in the hands of white

Southerners. Northerners justifiably feared that freedmen's basic rights of

citizenship would not be recognized, and considered it unsafe to restore the

Union until that discrimination was ended. Therefore the Republican majorities

in Congress refused to agree that the Southern states were ready to assume

their rights and did not seat the Southern congressional representatives. This

strained Johnson's relations with his party and convinced him that the entire

federal system, with its strict limits on national power, was in danger. When

Congress passed laws to protect the rights of the ex-slaves in 1866, he vetoed

them as unconstitutional and broke with the Republican Party completely rather

than endorse a new amendment to the Constitution granting blacks the rights of

citizenship. From this point forward Johnson's relations with the

congressional majority deteriorated. He questioned Congress's right to

legislate without the presence of Southern representatives, and he tacitly

encouraged Southern opposition to congressional laws.

Finally, in 1867, Congress set aside the governments Johnson had created in

the South and put Southerners under military supervision until new governments

based on equal civil and political rights were established. To Johnson this

marked the total subversion of the federal system, and he

resisted--cooperating with Democrats to encourage Southern resistance,

promoting a political reaction in the North, and hindering the Army's

enforcement of the laws in the South through his power as commander in chief.

When Johnson tried to gain control of the Army in February 1868, removing the

secretary of war in apparent violation of law, he was Impeached by the House

of Representatives and tried before the Senate. The excellence of Johnson's

lawyers, the ambiguity of the law, the cessation of his interference in the

South, the establishment of new governments there and the admission of their

representatives to Congress, and divisions among Republicans all led to a

verdict of "not guilty" by one vote. Johnson served out the

remainder of his term quietly.

Johnson's administration was ably served by its secretary of state, William

Henry Seward, who was instrumental in the purchase of Alaska from Russia in

1867. Seward was also vigorous, during the Civil War period under Lincoln and

later under Johnson, in protesting the French military intervention in Mexico

as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine. American diplomatic pressure increased,

and the French withdrew in 1866.

Returning to Tennessee, Johnson began rebuilding his eastern Tennessee

political base, seeking various Democratic nominations from 1869 to 1872. His

old enemies in the Tennessee Democratic party, however, frustrated his

ambitions. In 1874 he finally achieved the vindication he wanted so

desperately, winning election to the U.S. Senate by a coalition of Republicans

and dissident Democrats. On March 5, 1875, he once again took his seat in the

Senate. He died a few months later, on July 31.