Modern

Reprint Poster of the

Execution

of Jacques de Molay

The

Execution of Jacques De Molay

Lithograph

of the execution of Jacques DeMolay, Grand Master of the Templars, at Paris,

March 11, 1316. A realistic reproduction depicting a great

tragedy. This Lithograph is probably the best of any on this

subject. Circa 1900. Appeared in Mackey's History of Freemasonry.

In reality, they probably would have been naked,

or nearly so, and certainly not dressed in Templar mantles or regalia.

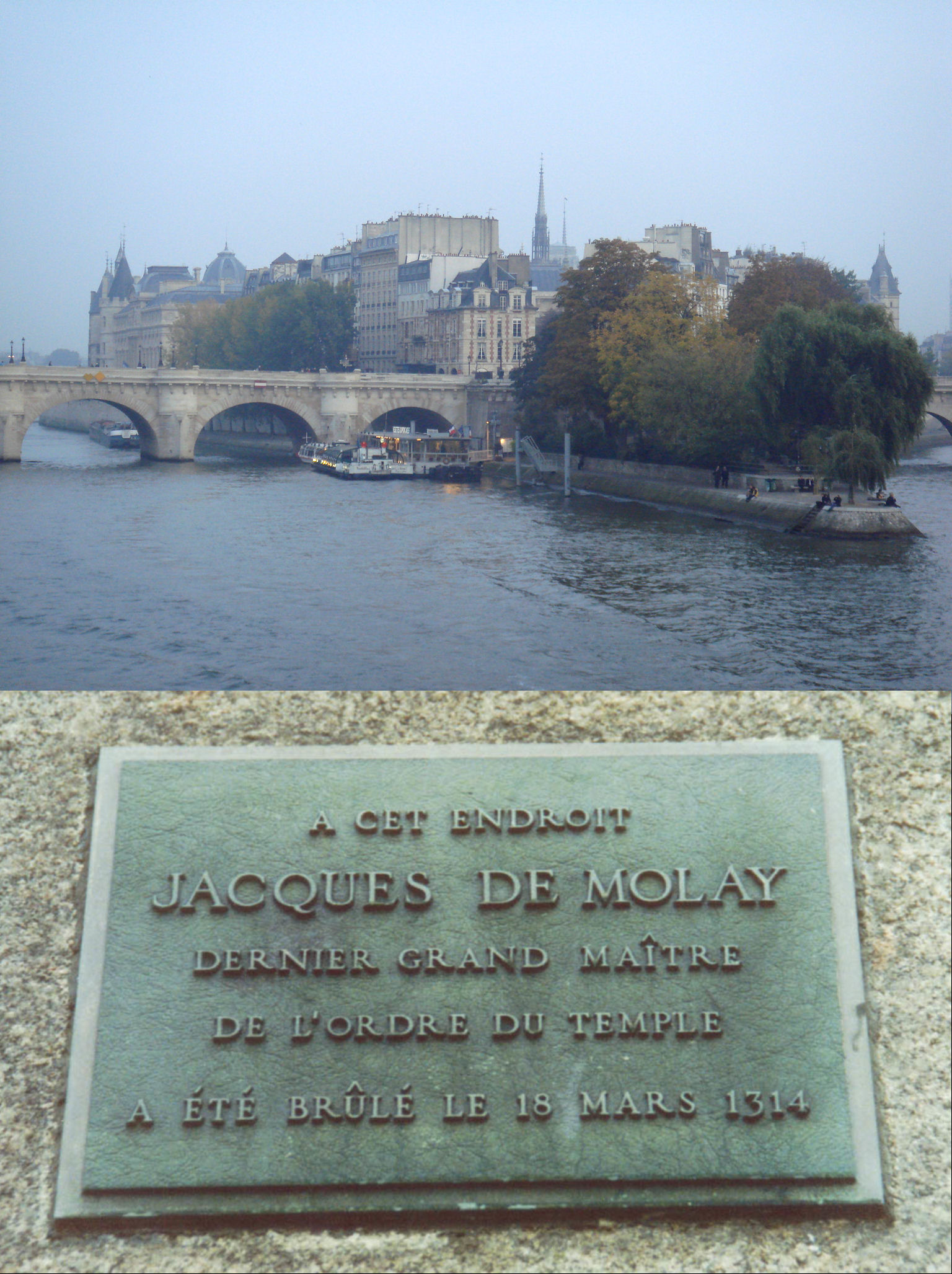

A special "ThankYou" to

Brother John Pattison

of Ontario,

Canada pictured above who submitted some interesting comments and two great

pictures that he took about this event in history.

DeMolay and De Charnay were burned in the middle

of the river on what was then a muddy islet due to safety considerations - no

one in his right mind would light a large, open fire in the middle of a wood

and thatch medieval city, not even the king. It is said the common people

waded out to the mud flats to collect as relics the cooled ashes, the sense

being that what had been done was seriously wrong, and that the cremated

remains held a virtue in themselves.

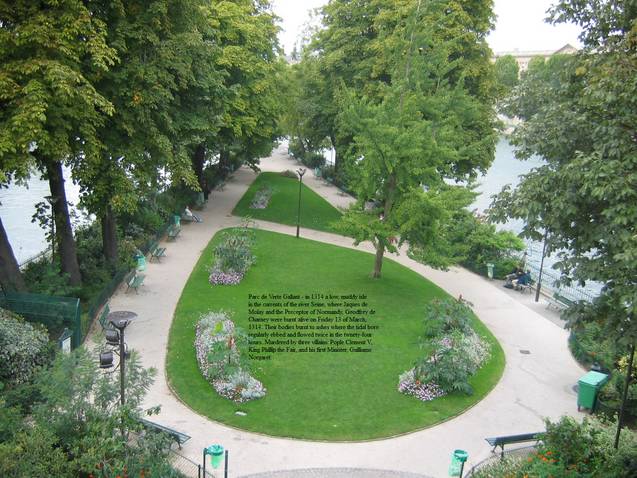

The current Parc de Verte Gallant refers to a later French King, who used the

groomed and raised area, no longer a mud flat, to dress in green and have

romantic assignations with "women of the town," as the euphemism was. Before

Versailles was built, the Louvre was the official royal palace, and was

located very close on the adjoining bank of the Seine where, indeed, it still

is.

Last Grand

Master of the Knights Templar

BY Lorne Pierce

32 degree

Past Assistant Grand Chaplain A.F.& A.M. Ontario

The origin of knighthood is lost

in the dim past. In early England a knight seems to have been a youth

who attended a member of the court; it was a position of honour and of service

and might lead in time to Royal recognition and rank. In Germany the

early knight may have been regarded much in the same way, a disciple. In both

countries the knights were obviously ambitious and high-spirited youths as one

might expect. It was in France, however, that the idea of chivalry

arose, and this conception quickly spread throughout Europe. Some

knights had made themselves useful to Earls or Bishops, that is the principal

landlords and magnates and military chiefs of the realm, and might be classed

as superior civil servants in times of peace, becoming leaders of the armies,

both secular and religious, in times of war. There were, of course, many

foot-loose knights wandering about Europe in quest of adventure, but on the

whole a knight was a responsible link in the Feudal chain reaching from the

king to the peasant. In time the ideal of chivalry came to prevail, and the

high honour accompanying it seems to have derived from prehistoric Teutonic

custom. The candidate had to submit to a rigorous investigation of his

character and qualifications. Then the community turned out to welcome

him with fitting ceremony and investiture with sword and shield, with belt and

sword, or with gilt spurs and collar, usually by the knight's father or some

exalted personage. In time t hose who had fought against the Saracens became

preeminent, and were accorded rank and dignity independent of birth or wealth.

The Knights Templar, or Poor

Fellow Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, was one of the three

out-standing military orders of the Middle Ages in Christendom. The

brotherhood was founded, about 1118, by Hugues de Payns, a nobleman residing

near Troyes, in Burgundy, and Godefroy de St. Omer (or Aldemar), a Norman

knight. Their original purpose was to protect pilgrims to sacred places,

more especially those who sought the Holy Sepulcher. At first there were eight

or nine Knights Templar. They bound themselves to each other as a

brotherhood in arms, and took upon themselves vows of chastity, obedience and

poverty according to the rule of St. Benedict. It is also recorded that

they pledged themselves to fight against ignorance, tyranny and the enemies of

the Holy Sepulcher, and "to fight with a pure mind for the supreme and

true King." Baldwin I, King of Jerusalem, assigned them accommodation in

his palace, which stood on the site of the Temple of Solomon. In this way

their name, Templars, was derived. At first the knights wore no uniform

or regalia, nothing in fact save the cast-off garments that were given to them

in charity. It was the poverty, sincerity and zeal of the order in its

first years that endowed it with importance. They sought out the poor

and the outcast, the excommunicated as well as the unwanted, and shepherded

them within their fold.

Hugues de Payns, accompanied by

several of his knights, returned home in 1127 for the purpose of securing

adequate ecclesiastical sanction for some of the special privileges which the

order had usurped. Among the very special privileges was immunity from

excommunication, which threatened a good deal of trouble. Bernard of

Clairvaux, the greatest abbot of his day, received Hugues de Payns, and not

only praised the Knights Templar, but went much further. The future St.

Bernard did not attend the Council of Troyes in 1128, at which the Rule of the

Temple was drawn up, but he seems to have inspired it - the constitution,

ritual, discipline and very core of the order. Finally there got abroad

the idea, that in the rule of the order there existed a "secret

rule," and a legend speedily grew up around this "lost word."

In time this was the undoing of the order. The whole Rule of the Temple

was probably never written out, its more essential parts being conveyed by

word of mouth, by symbol and sign, and protected by proper safeguards.

The point of importance was, that the order now had ample acknowledgement and

authority, and from this moment onward power and treasure flowed into its

hands in an unending and broadening stream.

The Templars and the Crusades

are forever associated in history and legend. The Templars, in an

astonishingly short time, spread over Christendom. They had thousands of

the fattest manors in the Christian world. They became the bankers of the age,

the money exchange between Europe and the East, the trust company of the time.

They provided loans to princes, dowries for queens, ransoms for great

warriors, safety deposit vaults for the treasure of emperors and popes.

Their chapters were the schools of diplomacy of the time, training grounds for

prospective rulers, colleges in commerce and finance, sanctuaries for all who

needed protection, high or low. It was inevitable that they should

attract to themselves the envy of the less fortunate orders and guilds.

In time, in fact before the death of St. Bernard, in 1153, they had not only

received the tribute of kings and cardinals in the form of lands and treasure,

but they freed themselves from the necessity of paying tax, tithe or tribute

to any power, prince or pope, which privilege they claimed as defender of the

Church. This was enough to bring upon themselves the inevitable

reckoning for overreaching ambition, but they went further, very much further.

They not only claimed exemption from excommunication, but claimed exemption

from all papal decrees except those specially aimed at them by name, and they

owed allegiance to no power or authority on earth except their own head, the

Bishop of Rome. They had become a separate social, economic, political

and religious order, cutting across and transcending kingdoms, principalities

and archdioceses, with only the Vice-gerent of God superior to their Grand

Master. The enormous powers of the Knights Templar were bound to be

challenged by the popes as well as kings who demanded loyalty within their

realms. The order found itself in increasingly compromising situations,

the victim of treachery on the part of kings and princes of the Church, or the

instigator of trickery and subterfuge on its own part to preserve its powers.

The King of France, Philip the Fair, set out to unite the Hospitallers and the

Templars into one grand order, The Knights of Jerusalem, the Grand Master of

which was always to be a prince of the royal house of France. The Grand

Master of the Knights Templar invariably was Master of the Templars at

Jerusalem, and in Cyprus after the loss of the Holy Land to the Turks.

He came in time to live in a sumptuous manner, befitting his great wealth and

vast powers. In th e field, during the campaigns, he occupied a great

tent, round, with the black and white pennant flying above its high peak,

bearing the red cross of the Templars. Regional Grand Commanders were

accorded similar honours and no one took precedence over them except the Grand

Master, when he was present.

We know little concerning the

initiation ceremonies of the Knights Templar. Probably there was some

cleansing ritual, robing in white, the all-night vigil and Holy Communion,

gilt spurs, sword or other gift of honour, and finally the oath and accolade.

Certainly the order was a Christian institution. Their war-cry Beauseant!

- also inscribed on their banners and pennants, pledged loyalty to their

friends and promised terror to their foes. Likewise both a prayer and a

pledge were the well-known words:

Non nobis,

Domine, non nobis, sed nomini tuo da gloriam.

(Not unto us, O

Lord, not unto us, but unto Thy Name be the glory.)

Jacques de Molay was the

twenty-second and last Grand Master of the Knights Templar. He was born

about 1240 at Besancon, in the Duchy of Burgundy, and was of noble but poor

family. He was admitted to the order of knighthood, in 1265, at Beaune

and proceeded shortly to the Holy Land, under the Grand Master William de

Beaujeu, to fight for the Holy Sepulchre. Jacques de Molay remained in

the Holy Land for many years, for he was still with the order in Jerusalem

when, about 1295, he was elected Grand Master upon the death of Grand Master

Gaudinius - Theobald de Gaudilai. After the loss of Palestine by the

Templars, de Molay took his few remaining knights to the Island of Cyprus.

In 1305 he was summoned to a conference with the Pope, Clement V, who stated

that he wished to consider measures for effecting a union between the rival

Templars and Hospitallers. A long and bitter feud had existed between

the two great orders. However, both had agreed not to accept disciplined

members who might desire to transfer their allegiance from one order to the

other. Also, in battle, it was permitted members who became hopelessly

separated from the main body of one order to rally under the cross of the

rival order if near.

Jacques de Molay, accompanied by

sixty knights, made a royal progress westward. He called upon the Pope

who consulted him regarding a further Crusade, and de Molay requested an

investigation into charges that were already being openly made against the

order. Finally he arrived in Paris with kingly pomp. Philip the Fair,

King of France, suddenly arrested every Knight Templar in France, October 13,

1307, de Molay and his sixty friends among them. They were brought

before the University of Paris and the charges read to them. De Molay

spent five and a half years in prison. Of those arrested, one hundred

and twenty-three knights of the order "confessed under the torture of the

Inquisition." Some confessed that at the initiation ceremonies they had

spat upon the Crucifix. When the Grand Master's turn came he likewise

confessed, apparently to bogus charges prepared beforehand by the Inquisition,

fearing torture, but he denied the charges of gross practices indignantly, and

demanded audience with the Pope. The Pope himself believed the Templers

were guilty, at least on some of the counts, but he resented the intrusion of

Philip in what he regarded as his own special precinct, in spite of the fact

that he largely owed his papal tiara to Philip.

Many retracted their confessions

regarding their indignity to the Crucifix, only to be burned at the stake.

Many who returned to their homes throughout Christendom, recanted, but the

Inquisition followed them and they burned. Despotism, naked and cruel,

without scruple or any capacity for shame, had broken loose upon the world. It

was a new and bloody technique that proved vastly effective in the hands of

tyrants - both secular and religious. Civilization

was to hear a good deal about this arbitrary rule, this summary and vindictive

totalitarianism, without conscience, hungry for power, wholly wicked,

completely mad. In 1311, Clement and Philip became reconciled, which prepared

the way for the final act in the tragedy. The next year, at Vienna, the

Pope condemned the order in a sermon while Philip sat at his right hand.

Later the inevitable occurred; the Knights Templar were broken up. Much

of their treasure was given to the Knights of St. John, but Philip the Fair

and Clement V reserved land and treasure, castles and Abbeys for themselves

and their friends.

No full hearing seems to have

been given to all the charges, or any comprehensive judgment handed down on

the order as a whole. However, in 1314, Jacques de Molay, whose fear had made

him a pathetic figure, and whose craven "confessions" contrary to

the oath of his order had sent hundreds to their death, again confessed, again

recanted his confession, again confessed, each time shrinking miserably in

stature both as a man and Grand Master and having humiliation and utter

disgrace heaped upon him for his pa ins. Finally, after the long

imprisonment and tragedy and sorrow of it all, he was led out upon the

scaffold in front of Notre Dame in Paris, in company with his friend Gaufrid

de Charney, Preceptor of Normandy. The papal legates were in attendance

and a vast multitude of people filled the square. He was to confess by

arrangement and hear the legates sentence him to life imprisonment. Jacques de

Molay finally atoned. Instead of confessing he proclaimed the innocence

of the order. King Philip the Fair did not hesitate or consult with the

Pope's legates; he had de Molay burned forthwith, "between the

Augustinians and the royal garden." Guido Delphini was burned with them,

and also the young son of the dauphin of Auvergne. With his dying breath

Jacques de Molay shouted to the multitude that King and Pope would soon meet

him before the judgment seat of God. The common people gathered up his

ashes, and before many days it was as de Molay had foretold, Both Clement V

and Philip the Fair were dead.

The immortal Dante maintained

the innocence of the Knights as did many another famous contemporary.

Today it is generally admitted that the Inquisition went to the poor knights

in prison, told them that their officers had confessed to spitting upon the

Crucifix, and then wrung from them "confessions" by the most brutal

of all institutions. The confessions are all discounted. The

evidence against them was from their rivals, the Dominicans and Franciscans

and others, all worthless.

The Order had long held the Turk

in check, and kept alive the dream of a united Christendom. It had given

to the world the idea of the chivalrous man as a religious man, the servant of

his state not ashamed to own his God. It had paved the way for the large

part laymen were to play in the religious life of the nations. It was

the school of diplomacy and commerce, of international finance and opinion.

Those who destroyed the order opened the way for Turkish conquests in the

West. They also made known the horrors of despotism, of trial by pogrom

and purge, which kindled again in the wicked days of St. Bartholomew's and in

the mad days of the French Revolution - the cult of cruelty, that ran its

course even in the New World with witch hunts and burnings, and that is not

yet dead. It has been said that the thirteenth of October, 1307, was a day of

humiliation for the whole race. If the world remembers, and recovers its sense

of shame, its capacity for indignation, it may not have been in vain.

The Middle Ages were past, and

deep rivers of Christian blood had flowed for two hundred and fifty years,

before the Turk was expelled from the Spanish peninsula. Under Don John

of Austria the Mediterranean states, organized into a league, sent an armada

of two hundred ships against the Turkish fleet that had sailed westward from

Cyprus and Crete. Christian met Saracen off Lepanto, October 7, 1571,

broke the naval power of the Turks forever and set

barricades to their western expansion to this day. Thus was October 13,

1307, at last avenged. Nearly every European state and noble family was

represented. There was also present a humble Spaniard who had his arm

shattered but who lived to write a book, with his one good hand, the novel Don

Quixote, that laughed the last dregs of a corrupt and bogus chivalry out of

Europe. He died in 1616, the year our Shakespeare died, and an era

ended. The era of the common man followed; a new day had dawned.