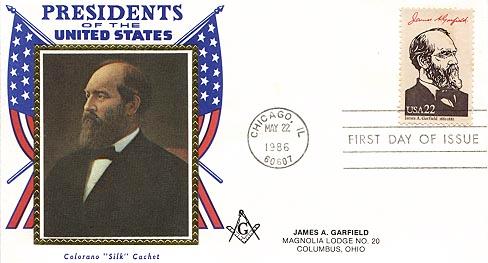

James A.

Garfield

Twentieth

President of the United States

As the last of the log cabin

Presidents, James A. Garfield attacked political corruption and won back for

the Presidency a measure of prestige it had lost during the Reconstruction

period.

He was born in Cuyahoga County,

Ohio, in 1831. Fatherless at two, he later drove canal boat teams, somehow

earning enough money for an education. He was graduated from Williams College

in Massachusetts in 1856, and he returned to the Western Reserve Eclectic

Institute (later Hiram College) in Ohio as a classics professor. Within a year

he was made its president.

Garfield was elected to the Ohio

Senate in 1859 as a Republican. During the secession crisis, he advocated

coercing the seceding states back into the Union.

In 1862, when Union military

victories had been few, he successfully led a brigade at Middle Creek,

Kentucky, against Confederate troops. At 31, Garfield became a brigadier

general, two years later a major general of volunteers.

Meanwhile, in 1862, Ohioans

elected him to Congress. President Lincoln persuaded him to resign his

commission: It was easier to find major generals than to obtain effective

Republicans for Congress. Garfield repeatedly won re-election for 18 years,

and became the leading Republican in the House.

At the 1880 Republican

Convention, Garfield failed to win the Presidential nomination for his friend

John Sherman. Finally, on the 36th ballot, Garfield himself became the

"dark horse" nominee.

By a margin of only 10,000

popular votes, Garfield defeated the Democratic nominee, Gen. Winfield Scott

Hancock.

As President, Garfield

strengthened Federal authority over the New York Customs House, stronghold of

Senator Roscoe Conkling, who was leader of the Stalwart Republicans and

dispenser of patronage in New York. When Garfield submitted to the Senate a

list of appointments including many of Conkling's friends, he named Conkling's

arch-rival William H. Robertson to run the Customs House. Conkling contested

the nomination, tried to persuade the Senate to block it, and appealed to the

Republican caucus to compel its withdrawal.

But Garfield would not submit:

"This...will settle the question whether the President is registering

clerk of the Senate or the Executive of the United States.... shall the

principal port of entry ... be under the control of the administration or

under the local control of a factional senator."

Conkling maneuvered to have the

Senate confirm Garfield's uncontested nominations and adjourn without acting

on Robertson. Garfield countered by withdrawing all nominations except

Robertson's; the Senators would have to confirm him or sacrifice all the

appointments of Conkling's friends.

In a final desperate move,

Conkling and his fellow-Senator from New York resigned, confident that their

legislature would vindicate their stand and re-elect them. Instead, the

legislature elected two other men; the Senate confirmed Robertson. Garfield's

victory was complete.

In foreign affairs, Garfield's

Secretary of State invited all American republics to a conference to meet in

Washington in 1882. But the conference never took place. On July 2, 1881, in a

Washington railroad station, an embittered attorney who had sought a consular

post shot the President.

Mortally wounded, Garfield lay

in the White House for weeks. Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the

telephone, tried unsuccessfully to find the bullet with an induction-balance

electrical device which he had designed. On September 6, Garfield was taken to

the New Jersey seaside. For a few days he seemed to be recuperating, but on

September 19, 1881, he died from an infection and internal hemorrhage.