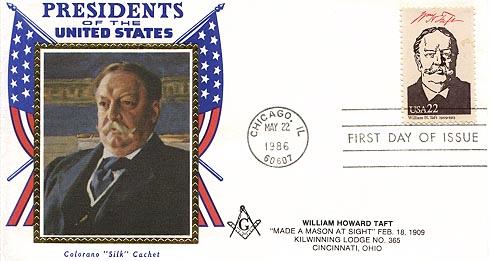

William

Howard Taft

27th

President of the United States

Distinguished jurist, effective

administrator, but poor politician, William Howard Taft spent four

uncomfortable years in the White House. Large, jovial, conscientious, he

was caught in the intense battles between Progressives and conservatives, and

got scant credit for the achievements of his administration.

Born in 1857, the son of a

distinguished judge, he was graduated from Yale, and returned to Cincinnati to

study and practice law. He rose in politics through Republican judiciary

appointments, through his own competence and availability, and because, as he

once wrote facetiously, he always had his "plate the right side up when

offices were falling."

But Taft much preferred law to

politics. He was appointed a Federal circuit judge at 34. He aspired to be a

member of the Supreme Court, but his wife, Helen Herron Taft, held other

ambitions for him.

His route to the White House was

via administrative posts. President McKinley sent him to the Philippines in

1900 as chief civil administrator. Sympathetic toward the Filipinos, he

improved the economy, built roads and schools, and gave the people at least

some participation in government.

President Roosevelt made him

Secretary of War, and by 1907 had decided that Taft should be his successor.

The Republican Convention nominated him the next year.

Taft disliked the

campaign--"one of the most uncomfortable four months of my life."

But he pledged his loyalty to the Roosevelt program, popular in the West,

while his brother Charles reassured eastern Republicans. William Jennings

Bryan, running on the Democratic ticket for a third time, complained that he

was having to oppose two candidates, a western progressive Taft and an eastern

conservative Taft.

Progressives were pleased with

Taft's election. "Roosevelt has cut enough hay," they said;

"Taft is the man to put it into the barn." Conservatives were

delighted to be rid of Roosevelt--the "mad messiah."

Taft recognized that his

techniques would differ from those of his predecessor. Unlike Roosevelt, Taft

did not believe in the stretching of Presidential powers. He once commented

that Roosevelt "ought more often to have admitted the legal way of

reaching the same ends."

Taft alienated many liberal

Republicans who later formed the Progressive Party, by defending the

Payne-Aldrich Act which unexpectedly continued high tariff rates. A trade

agreement with Canada, which Taft pushed through Congress, would have pleased

eastern advocates of a low tariff, but the Canadians rejected it. He further

antagonized Progressives by upholding his Secretary of the Interior, accused

of failing to carry out Roosevelt's conservation policies.

In the angry Progressive

onslaught against him, little attention was paid to the fact that his

administration initiated 80 antitrust suits and that Congress submitted to the

states amendments for a Federal income tax and the direct election of

Senators. A postal savings system was established, and the Interstate Commerce

Commission was directed to set railroad rates.

In 1912, when the Republicans re-nominated

Taft, Roosevelt bolted the party to lead the Progressives, thus guaranteeing

the election of Woodrow Wilson.

Taft, free of the Presidency,

served as Professor of Law at Yale until President Harding made him Chief

Justice of the United States, a position he held until just before his death

in 1930. To Taft, the appointment was his greatest honor; he wrote: "I

don't remember that I ever was President."