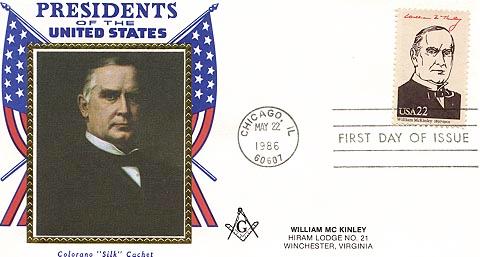

William

McKinley

25th

President of the United States

At the 1896 Republican

Convention, in time of depression, the wealthy Cleveland businessman Marcus

Alonzo Hanna ensured the nomination of his friend William McKinley as

"the advance agent of prosperity." The Democrats, advocating the

"free and unlimited coinage of both silver and gold"--which would

have mildly inflated the currency--nominated William Jennings Bryan.

While Hanna used large contributions from eastern Republicans frightened by

Bryan's views on silver, McKinley met delegations on his front porch in

Canton, Ohio. He won by the largest majority of popular votes since 1872.

Born in Niles, Ohio, in 1843, McKinley briefly attended Allegheny College, and

was teaching in a country school when the Civil War broke out. Enlisting as a

private in the Union Army, he was mustered out at the end of the war as a

brevet major of volunteers. He studied law, opened an office in Canton, Ohio,

and married Ida Saxton, daughter of a local banker.

At 34, McKinley won a seat in Congress. His attractive personality, exemplary

character, and quick intelligence enabled him to rise rapidly. He was

appointed to the powerful Ways and Means Committee. Robert M. La Follette,

Sr., who served with him, recalled that he generally "represented the

newer view," and "on the great new questions .. was generally on the

side of the public and against private interests."

During his 14 years in the House, he became the leading Republican tariff

expert, giving his name to the measure enacted in 1890. The next year he was

elected Governor of Ohio, serving two terms.

When McKinley became President, the depression of 1893 had almost run its

course and with it the extreme agitation over silver. Deferring action on the

money question, he called Congress into special session to enact the highest

tariff in history.

In the friendly atmosphere of the McKinley Administration, industrial

combinations developed at an unprecedented pace. Newspapers caricatured

McKinley as a little boy led around by "Nursie" Hanna, the

representative of the trusts. However, McKinley was not dominated by Hanna; he

condemned the trusts as "dangerous conspiracies against the public

good."

Not prosperity, but foreign policy, dominated McKinley's Administration.

Reporting the stalemate between Spanish forces and revolutionaries in Cuba,

newspapers screamed that a quarter of the population was dead and the rest

suffering acutely. Public indignation brought pressure upon the President for

war. Unable to restrain Congress or the American people, McKinley delivered

his message of neutral intervention in April 1898. Congress thereupon voted

three resolutions tantamount to a declaration of war for the liberation and

independence of Cuba.

In the 100-day war, the United States destroyed the Spanish fleet outside

Santiago harbor in Cuba, seized Manila in the Philippines, and occupied Puerto

Rico.

"Uncle Joe" Cannon, later Speaker of the House, once said that

McKinley kept his ear so close to the ground that it was full of grasshoppers.

When McKinley was undecided what to do about Spanish possessions other than

Cuba, he toured the country and detected an imperialist sentiment. Thus the

United States annexed the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico.

In 1900, McKinley again campaigned against Bryan. While Bryan inveighed

against imperialism, McKinley quietly stood for "the full dinner

pail."

His second term, which had begun auspiciously, came to a tragic end in

September 1901. He was standing in a receiving line at the Buffalo

Pan-American Exposition when a deranged anarchist shot him twice. He

died eight days later.