George

Washington Laying the Cornerstone of the United States Capital

Mural and

Commemorative Medallion

This majestic mural was the work

of Allyn Cox, one of the most talented muralists in America. Cox worked for

approximately 30 years at the Capitol building; he painted 26 murals in the

House side, one in the Senate side and the frieze on the Capitol dome.

The mural shows President Washington receiving a silver plate which was

deposited underneath the Cornerstone of the United States Capitol at the Masonic

Ceremony he conducted under the auspices of the Grand Lodge of Maryland.

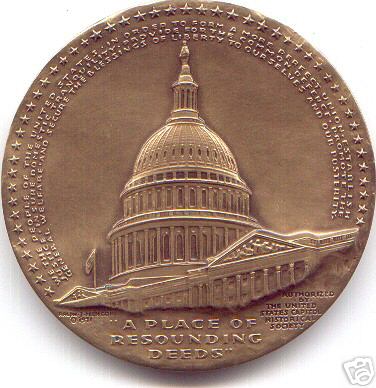

This beautiful medallion depicts and

commemorates the 180th Anniversary of the laying of the Cornerstone of the U.S. Capital by Brother

George Washington on September 18, 1793. He is shown wearing his Masonic Jewel

and Apron and spreading the the cement of Brotherly Love and Affection with

his Masonic Trowel. This medal was made in 1971 and released in

1973. The medal is bronze, it is 2 1/2 inches in diameter & in uncirculated

condition. The medallist was Ralph J. Menconi and it was authorized by the

United States Capitol Historical Society. The obverse shows George Washington

in full Masonic regalia, applying the cement of Brotherly Love to a suspended

cornerstone. There is an Eagle at the top and medallions of the U.S. Capitol

on the left and U.S. Senate shield on the right. To the bottom right it reads

"CORNERSTONE - OF CAPITOL - LAID - SEPTEMBER 18TH - 1793". The reverse shows

the Capitol rotunda's exterior and below the building it reads "A PLACE OF -

RESOUNDING - DEEDS". To the bottom right it reads "AUTHORIZED - BY - THE

UNITED - STATES CAPITOL - HISTORICAL - SOCIETY". Around the top portion there

is a rim of stars and a three line inscription beginning with "WE THE PEOPLE

OF THE UNITED STATES".

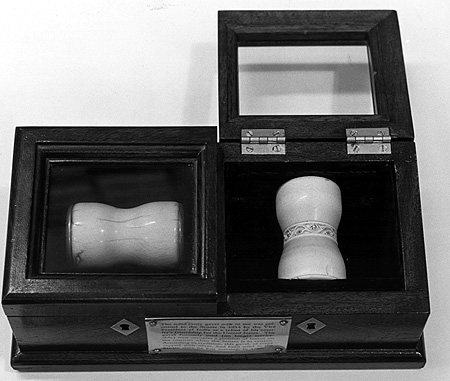

The tools used at the cornerstone ceremony,

on display at the George Washington Masonic Memorial in Alexandria, VA

After the reading of the

inscription, the cornerstone was made ready. President Washington, the Grand

Master pro tempore Joseph Clark of Maryland, and the three attending Masters of

the lodges present—Elisha Cullen Dick of Alexandria No. 22, Valentine Reintzel

of Maryland Lodge No. 9, and James Hoban of Federal Lodge No. 15—took the plate

and stepped down into the trench. A beautiful silver trowel and marble gavel had

been crafted especially for the occasion by Brother John Duffey, a silversmith

in Alexandria who was a member of the president’s home lodge, Fredericksburg

Lodge No. 4. The trowel had a silver blade, a silver shank and an ivory handle

with a silver cap. Brother Duffey had also crafted Masonic working tools of

walnut for use in the ceremony.

The square was applied, a symbol

of virtue, to make certain that each angle of the stone was perfectly cut. Next,

the level, a symbol of equality, was used it to ascertain that the stone was

horizontally correct. And last, the plumb, an emblem of morality and rectitude,

showed that the stone was perfectly upright. The stone was declared square,

level and plumb and therefore suitable as the foundation for the new building.

Kernels of wheat were sprinkled over the stone from a golden cup as a symbol of

goodness, plenty and nourishment. Wine was poured over it from a silver cup, a

symbol of friendship, health and refreshment. Finally, drops of oil glistened

down its sides like the sacred oil that ran down upon Aaron’s beard in the Old

Testament, “to the skirts of his garments; as the dew of Hermon, and as the dew

that descended upon the mountains of Zion.” The oil symbolized joy, peace and

tranquility.

President Washington placed the silver plate on the cornerstone, and it was

consecrated in the Masonic tradition with corn, wine and oil. The silver trowel

was used to spread a small amount of cement, and the marble gavel to

symbolically tap the stone into place.

Today, the left “valve” doors of the Senate depict a scene from the laying of

the Capitol cornerstone, clearly showing Washington in his Masonic apron, and

there is a fresco painted in the Capitol depicting the scene, as well.

Non-Masons may be especially curious about the “year of Masonry” on the

cornerstone’s plate—5793. One of the more confounding customs has to do with the

way Freemasons date documents. The Gregorian calendar was standardized by Pope

Gregory XIII in 1582, though the non-Catholic Western world took another 200

years before they went along with the pope’s idea. Since 1776, most of the world

has been on the same calendar page, though Greece and Russia didn’t adopt it

until after World War I. Because Western Europe and America switched to the

Gregorian calendar in the mid-1700s, conflicting ages are attributed to some of

the notable figures of the period. Because of the confusion during the

changeover, they themselves weren’t always sure of their real age.

In 1658, Bishop James Ussher in Ireland believed he had determined the exact

date of the creation of the world. Using the biblical account along with a

comparison of Middle Eastern histories, Hebrew genealogy and other known events,

he determined that the Earth was created on Sunday, October 23, 4004 B.C. At

about the same time, John Lightfoot, vice chancellor of Cambridge University,

went on to clarify that the Creation actually happened at about 9 a.m.

Ussher called his calendar Anno

Mundi, the Year of the World. By 1700, Ussher and Lightfoot’s calculations of

the date and time of the Creation were accepted as fact by most Christian

denominations. Beginning in 1701, new editions of the King James Bible clearly

stated it right up front. Because Ussher’s Creation date was so strongly

believed at the time of modern Freemasonry’s origin, the Masons began dating

their documents using 4004 B.C. as their beginning year . . . sort of. 4004 was

an inconvenient number to remember, so Masons simply took the current year and

added 4,000 to it. So, A.D. 1793 became 5793 Anno Lucis, or A.L., and A.D. 2007

would be 6007 A.L. Anno Lucis means “year of light” in Latin. Masons called it

that to coincide with the Genesis passage, “And God said, ‘Let there be light’;

and there was light.” They did this early on to lend their fraternity an air of

great and solemn antiquity. If they dated their documents as being 5717 years

old, they’d certainly sound more respectable and impressive than some newly

formed London drinking club. Today, you will often see two dates on Masonic

cornerstones—both A.D. and A.L.

After seven years, the U.S.

Congress met in the first completed portion of the Capitol, the North Wing, in

November 1800. In the 1850s, major extensions to the North and South ends of the

Capitol were required because of rapid westward expansion of the country and the

subsequent growth of Congress. During this expansion, the distinctive dome that

makes the building so readily identifiable replaced a less grandiose, much

shorter, squatter (and leaky) one that made up Dr. Thornton’s original design.

Since that time, additional office buildings have been built up on streets

adjacent to the Capitol to handle the needs of an ever-increasing, swollen

bureaucracy.

Because of modifications to the

building following its burning in 1814 at the hands of the British, along with

expansions in the 1850s, the original cornerstone laid by George Washington and

the Freemasons has been lost. In 1893, on the one hundredth anniversary of the

laying of the Capitol’s cornerstone, a plaque was placed near the spot where it

was believed to have originally been installed.

Beneath this tablet

the corner stone of the Capitol of the

United States of America

was laid by

George Washington

First President September 18, 1793

On the Hundredth Anniversary

in the year 1893

In presence of the Congress the Executive and the

Judiciary

a vast concourse of the grateful people

of the District of Columbia commemorated the

event.

Grover Cleveland President of the United States

Adlai Ewing Stevenson Vice President

Charles Frederick Crisp Speaker, House of

Representatives

Daniel Wolsey Hoorhees Chairman Joint Committee of

Congress,

Lawrence Gardner Chairman Citizens Committee

The United

States Senate Gavel

The

unique gavel of the

United States Senate has an

hourglass

shape and no handle. The gavel in current use was presented to the Senate by

the Republic of

India and first used on November 17, 1954. This gavel replaced an

ivory gavel

which had been in use since at least 1789 and had deteriorated over the years.

In 1952, silver plates were added to both ends of the old gavel in an attempt

to prevent further damage to it. In 1954, it broke when

Vice President

Richard Nixon used it during a heated debate on

nuclear energy. Unable to obtain a piece of ivory large enough to replace

the gavel, the Senate appealed to the

Indian embassy. India presented to the United States the solid ivory

replica

still in use.[4]

The Unites

States House of Representatives Mace

History

In one of its first resolutions,

the

U.S. House of Representatives of the

1st Federal Congress (April 14, 1789) established the

Office of the Sergeant at Arms. The first

Speaker of the House,

Frederick Muhlenberg of

Pennsylvania, approved the

ceremonial mace as the proper symbol of the Sergeant at Arms in carrying out

the duties of this office.

The current mace has been in use

since December 1, 1842. It was created by New York

silversmith William Adams, at a cost of $400, to replace the first one that

was destroyed when the

Capitol Building was burned on August 24, 1814 during the

War of

1812. A simple wooden mace was used in the interim.

Description

The design of the mace is derived

from an

ancient battle weapon and the

Roman fasces.

The ceremonial mace is 46 inches high and consists of 13

ebony rods –

representing the

original 13 states of the

Union

– bound together by silver strands criss-crossed over the length of the pole.

Atop this shaft is a silver globe on which sits an intricately cast solid silver

eagle.

Sitting above the ebony rods of

the mace is a cast-silver globe, which holds an eagle with spread wings. The

continents are etched into the globe, with North America facing front. The

eagle, the national bird, is cast in solid silver.

Procedure

For daily sessions of the House,

the Sergeant carries the silver and ebony mace of the House in front of the

speaker, in procession to the

rostrum. When

the House is in

session, the mace stands on a cylindrical pedestal of green

marble to the

Speaker's right. When the House is in

committee, it is moved to a pedestal next to the Sergeant at Arms' desk.[1]

Thus, members entering the chamber know immediately whether the House is in

session or in committee. When the body resolves itself into

Committee of the whole House on the State of the Union, the Sergeant moves

the mace to a lowered position, more or less out of sight.

Disciplinary usage

In accordance with the

House Rules, on the rare occasion that a

member becomes unruly, the Sergeant at Arms, upon order of the Speaker,

lifts the mace from its pedestal and presents it before the offenders, thereby

restoring order.

When a confrontation on the House

floor becomes unruly, the tradition is that, upon direction of the Speaker, the

Sergeant at Arms will step between the combatants with the mace. Usually,

because the members are able to edit the

Congressional Record before it goes to print, there is no mention of the

actual use of the mace in this capacity. The most recent recorded use of the

mace was on July 29, 1994, when Democratic Rep.

Maxine Waters failed to stop speaking after she was accused of insulting

Rep.

Peter T. King.

From

Wikipedia