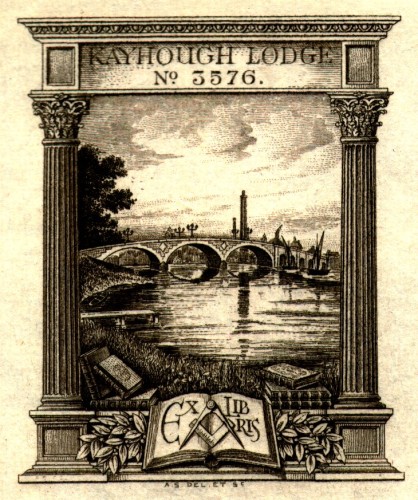

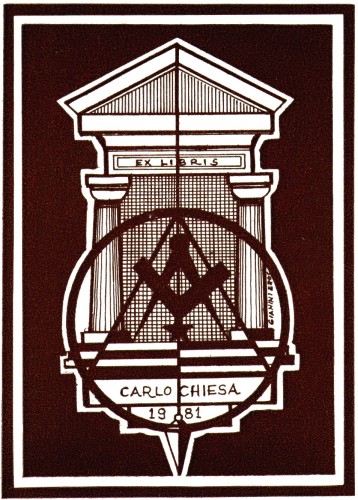

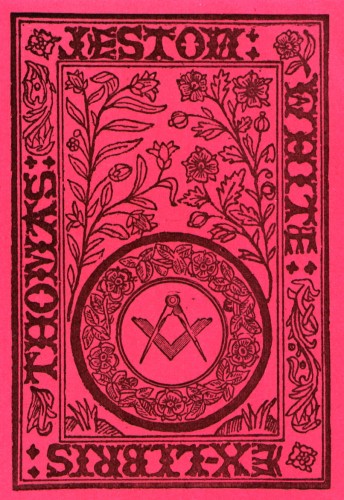

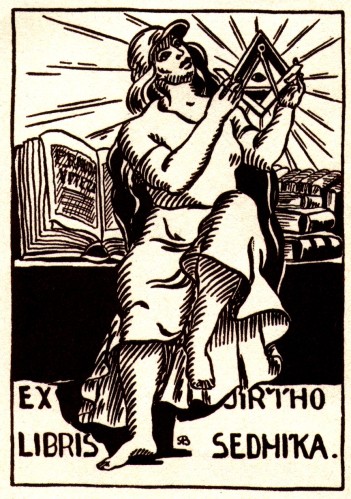

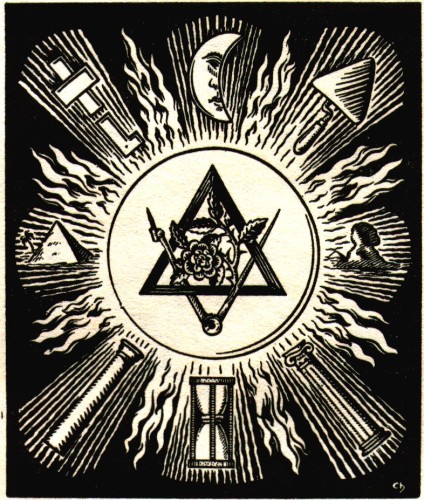

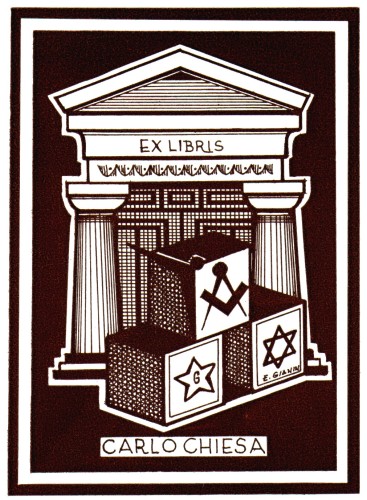

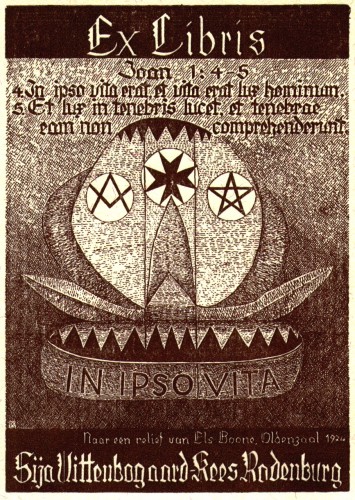

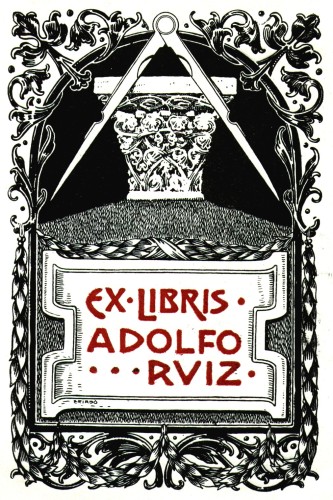

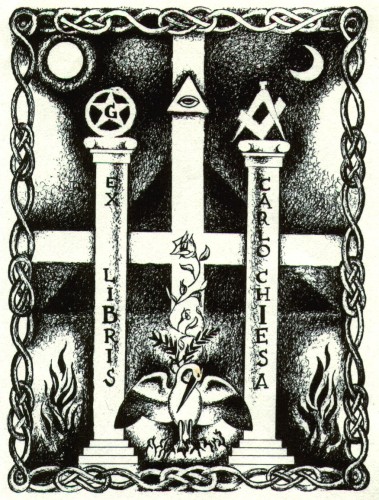

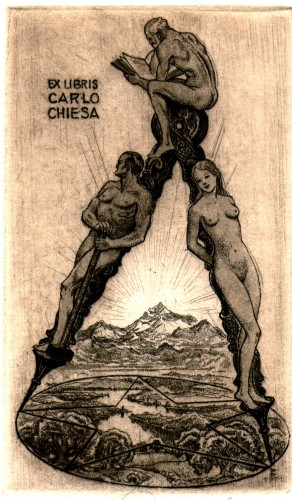

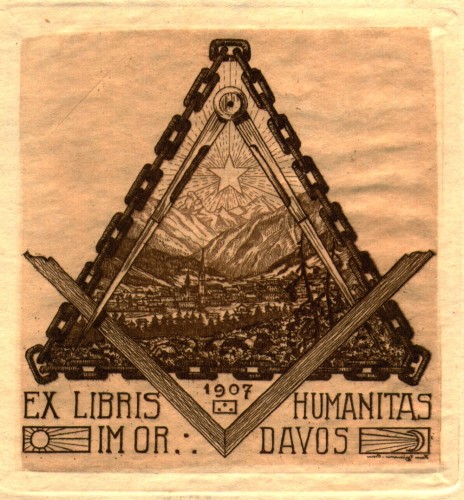

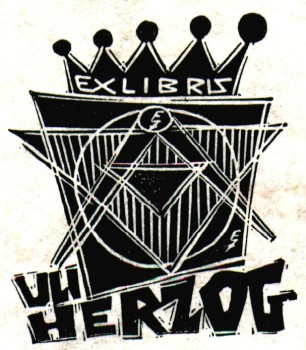

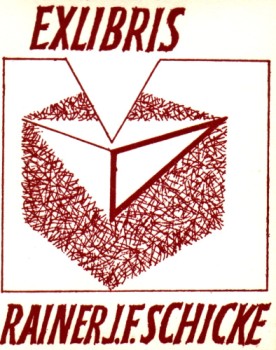

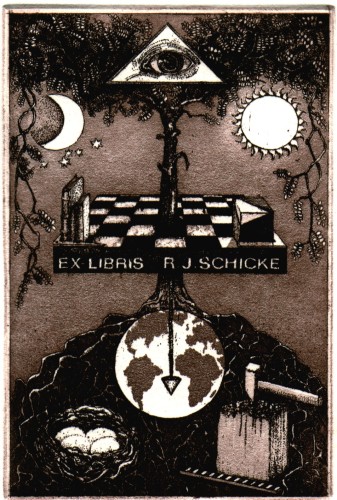

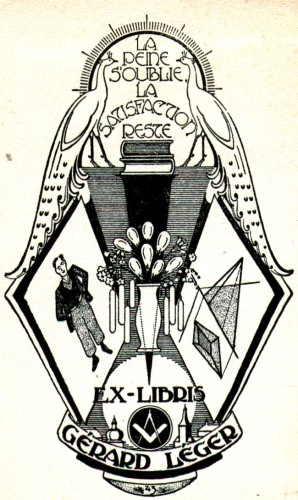

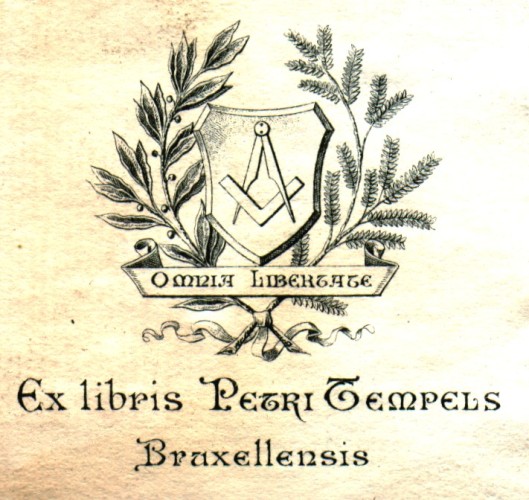

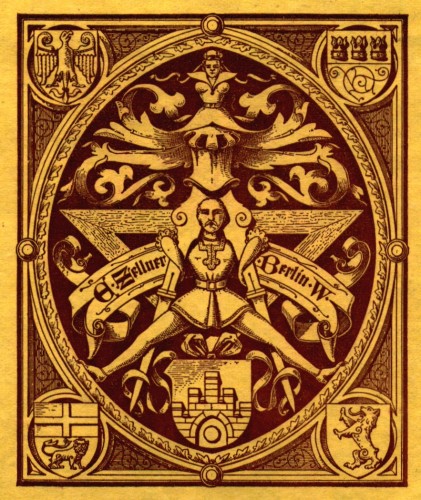

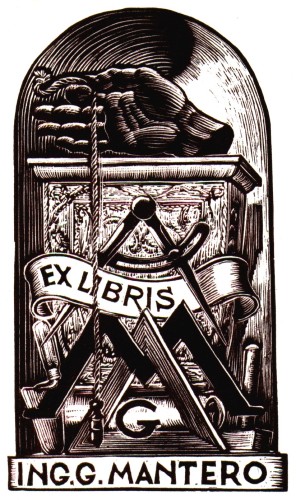

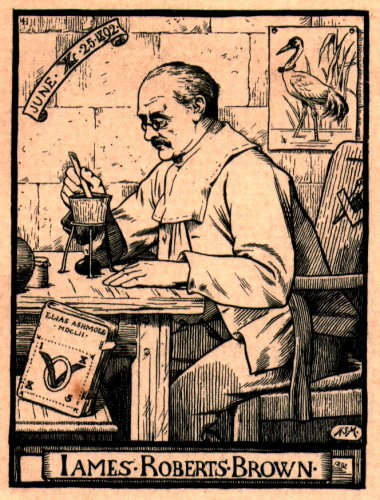

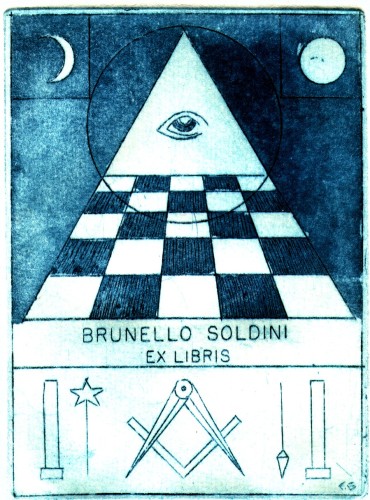

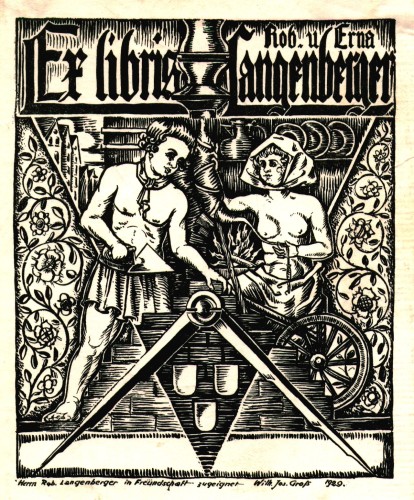

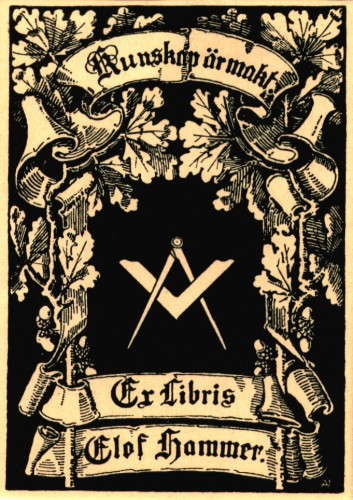

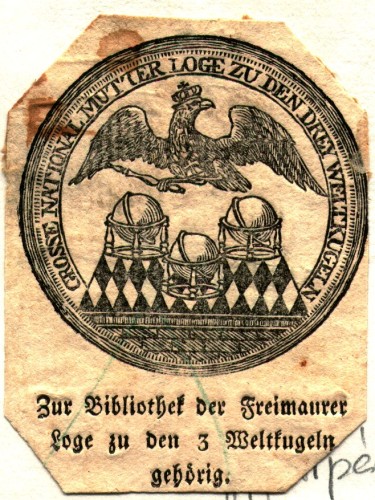

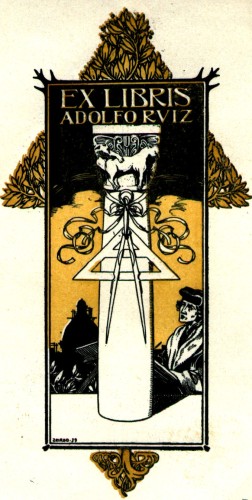

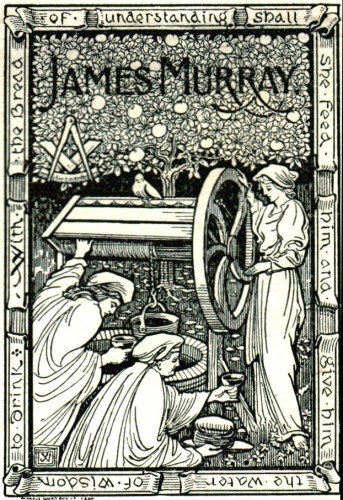

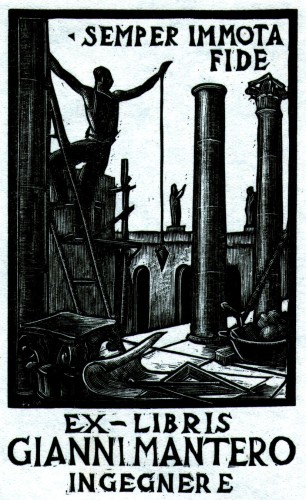

A Collection

of Masonic Bookplates or Ex-Libris

Masonic

bookplate bookplates are probably the rarest of all genres.

This collection belonging to Brother Jens Rusch of

http://freimaurer-wiki.de/index.php/Freimaurer-Exlibris is therefore a small but

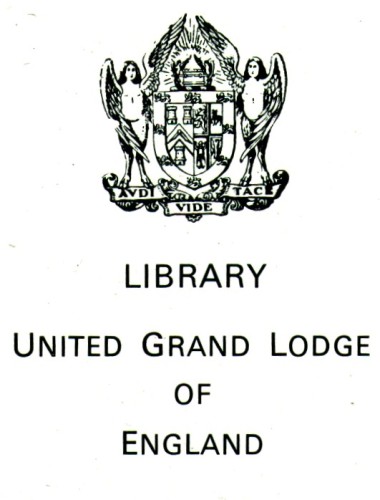

valuable selection. Formerly it was reserved for monastery libraries to

declare ownership. In these specimens there are also the official

bookplate of UGLE- library. The

following is a detailed definition from Wikipedia.

A bookplate, also known as ex-librīs

[Latin,

"from the books of..."], is usually a small print or decorative label pasted

into a book, often on the inside front cover, to indicate its owner. Simple

typographical bookplates are termed 'booklabels'.

Bookplates typically bear a

name,

motto,

device,

coat-of-arms,

crest,

badge, or any motif that relates to the owner of the book, or is requested

by him from the artist or designer. The name of the owner usually follows an

inscription such as "from the books of . . . " or "from the library of . . . ",

or in Latin, ex libris .... Bookplates are important evidence for the

provenance of books.

The earliest known marks of ownership of books or

documents date from the reign of Amenophis III in Egypt (1391-1353). However, in

their modern form, they evolved from simple inscriptions in books which were

common in Europe in the Middle Ages, when various other forms of "librarianship"

became widespread (such as the use of class-marks, call-numbers, or shelfmarks).

The earliest known examples of printed bookplates are German, and date from the

15th century. One of the best known is a small hand-coloured woodcut

representing a shield of arms supported by an angel, which was pasted into books

presented to the

Carthusian monastery of Buxheim by Brother Hildebrand Brandenburg of

Biberach, about the year 1480—the date being fixed by that of the recorded

gift. The woodcut, in imitation of similar devices in old manuscripts, is

hand-painted. An example of this bookplate can be found in the Farber Archives

of

Brandeis University[1]

. In France the most ancient ex-libris as yet discovered is that of one Jean

Bertaud de la Tour-Blanche, the date of which is 1529.

Holland comes next with the plate of Anna van der Aa, in 1597; then Italy

with one attributed to the year 1622. The earliest known American example is the

plain printed label of John Williams, 1679.

England

In many ways the consideration of the English

bookplate, in its numerous styles, from the late

Elizabethan to the late

Victorian period, is particularly interesting. In all its varieties it

reflects with great fidelity the prevailing taste in decorative art at different

epochs - as bookplates do in all countries. Of English examples, none thus far

seems to have been discovered of older date than the gift plate of

Sir Nicholas Bacon; for the celebrated, gorgeous, hand-painted armorial

device attached to a

folio that once belonged to Henry VIII, and now is located in the King's

library,

British Museum, does not fall in the category of bookplates in its modern

sense. The next is that of Sir Thomas Tresham, dated 1585. Until the last

quarter of the 17th century the number of authentic English plates is very

limited. Their composition is always remarkably simple, and displays nothing of

the German elaborateness. They are as a rule very plainly armorial, and the

decoration is usually limited to a symmetrical arrangement of mantling, with an

occasional display of palms or wreaths. Soon after the Restoration, however, a

bookplate seems to have suddenly become an established accessory to most

well-ordered libraries.

The first recorded use of the phrase book

plate was in 1791 by John Ireland in Hogarth Illustrated. Bookplates

of that period offer very distinctive characteristics. In the simplicity of

their heraldic arrangements they recall those of the previous age; but their

physiognomy is totally different. In the first place, they invariably display

the

tincture lines and dots, after the method originally devised in the middle

of the century by Petra Sancta, the author of Tesserae Genlilitiae, which

by this time had become adopted throughout Europe. In the second, the mantling

assumes a much more elaborate appearance—one that irresistibly recalls that of

the

periwig of the period surrounding the face of the shield. This style was

undoubtedly imported from France, but it assumed a character of its own in

England.

As a matter of fact, from then until the dawn of

the

French Revolution, English modes of decoration in bookplates, as in most

other chattels, follow at some years' distance the ruling French taste. The main

characteristics of the style which prevailed during the

Queen Anne and early Georgian periods are: ornamental frames suggestive of

carved oak, a frequent use of fish-scales,

trellis or diapered patterns, for the decoration of plain surfaces; and, in

the armorial display, a marked reduction in the importance of the mantling. The

introduction of the scallop-shell as an almost constant element of ornamentation

gives already a foretaste of the Rocaille-Coquille, the so-called Chippendale

fashions of the next reign. As a matter of fact, during the middle third of

the century this

rococo style (of which the Convers plate gives a typical sample) affects the

bookplate as universally as all other decorative objects. Its chief element is a

fanciful arrangement of scroll and shell work with curveting acanthus-like

sprays — an arrangement which in the examples of the best period is generally

made asymmetrical in order to give freer scope for a variety of countercurves.

Straight or concentric lines and all appearances of flat surface are studiously

avoided; the helmet and its symmetrical mantling tends to disappear, and is

replaced by the plain crest on a fillet. The earlier examples of this manner are

tolerably ponderous and simple. Later, however, the composition becomes

exceedingly light and complicated; every conceivable and often incongruous

element of decoration is introduced, from cupids to dragons, from flowerets to

Chinese pagodas. During the early part of George III.'s reign there is a return

to greater sobriety of ornamentation, and a style more truly national, which may

be called the urn style, makes its appearance. Bookplates of this period have

invariably a physiognomy which at once recalls the decorative manner made

popular by architects and designers such as Chambers, the Adams, Josiah

Wedgwood, Hepplewhite and Sheraton. The shield shows a plain spade-like outline,

manifestly based upon that of the pseudo-classic

urn then very alive. The ornamental accessories are symmetrical palms and

sprays, wreaths and

ribands. The architectural boss is also an important factor. In many plates,

indeed, the shield of arms takes quite a subsidiary position by the side of the

predominantly architectural urn.

From the beginning of the 19th century, no

special style of decoration seems to have established itself. The immense

majority of examples display a plain shield of arms with motto on a scroll, and

crest on a fillet. At the turn of the 20th century, however, a rapid impetus

appears to have been given to the designing of ex-libris; a new era, in fact,

had begun for the bookplate, one of great interest.

The main styles of decoration (and these, other

data being absent, must always in the case of old examples remain the criteria

to date) have already been noticed. It is, however, necessary to point out that

certain styles of composition were also prevalent at certain periods. Although

the majority of the older plates were armorial, there were always pictorial

examples as well, and these are the quasi-totality of modern ones.

Of this kind the best-defined English

genre may be recalled: the library interior—a term which explains

itself—and book-piles, exemplified by the ex-libris of W. Hewer,

Samuel Pepys's secretary. We have also many portrait-plates, of

which, perhaps, the most notable are those of Samuel Pepys himself and of John

Gibbs, the architect; allegories, such as were engraved by Hogarth,

Bartolozzi, John Pine and George Vertue; landscape-plates, by

wood-engravers of the Bewick school, &c. In most of these the armorial element

plays but a secondary part.

Art

Until the advent of bookplate collectors and

their frenzy for exchange, the devising of bookplates was almost invariably left

to the routine skill of the heraldic-stationery salesman. Near the turn of the

20th century, the composition of personal book tokens became recognized as a

minor branch of a higher art, and there has come into fashion an entirely new

class of designs which, for all their wonderful variety, bear as unmistakable a

character as that of the most definite styles of bygone days. Broadly speaking,

it may be said that the purely heraldic element tends to become subsidiary and

the

allegorical or symbolic to assert itself more strongly.

Among early 20th-century English artists who have

more specially paid attention to the devising of bookplates, may be mentioned

C. W. Sherborn, G. W. Eve,

Robert Anning Bell, J. D. Batten, Erat Harrison, J. Forbes Nixon,

Charles Ricketts, John Vinycomb, John Leighton and Warrington Hogg and

Frank C. Papé. The development in various directions of process work, by

facilitating and cheapening the reproduction of beautiful and elaborate designs,

has no doubt helped much to popularize the bookplate — a thing which in older

days was almost invariably restricted to ancestral libraries or to collections

otherwise important. Thus the great majority of plates of the period 1880-1920

plates were reproduced by process. Some artists continued to work with the

graver. Some of the work they produce challenges comparison with the finest

productions of bygone engravers. Of these the best-known are C. W. Sherborn (see

Plate) and G. W. Eve in England, and in America J. W. Spenceley of Boston,

Mass., K. W. F. Hopson of New Haven, Conn., and

E. D. French of New York City.

Study and collection

Bookplates are very often of high interest (and

of a value often far greater than the odd volume in which they are found

affixed), either as specimens of bygone decorative fashion or as personal relics

of well-known people. However the value attached to book plates, otherwise than

as an object of purely personal interest, is comparatively modern.

The study of and the taste for collecting

bookplates hardly date farther back than the year 1860. The first real impetus

was given by the appearance of A Guide to the Study of Book-Plates (Ex-Libris),

by Lord de Tabley (then the Hon. J. Leicester Warren M.A.) in 1880 (published in

London by John Pearson of 46 Pall Mall). This work, highly interesting from many

points of view, established what is now accepted as the general classification

of styles of British ex-libris: early armorial (i.e., previous to

Restoration, exemplified by the Nicholas Bacon plate); Jacobean, a

somewhat misleading term, but distinctly understood to include the heavy

decorative manner of the Restoration, Queen Anne and early Georgian days (the

Lansanor plate is Jacobean); Chippendale (the style above described as

rococo, tolerably well represented by the French plate of Convers);

wreath and ribbon, belonging to the period described as that of the urn, &c.

Since then the literature on the subject has grown considerably.

Societies of collectors were founded, first in

England in 1891, then in Germany and France, and later in the United States,

most of them issuing a journal or archives: The Journal of the Ex-libris

Society (London), the Archives de la Société française de collectionneurs

d'ex-libris (Paris), both of these monthlies; the Ex-libris Zeitschrift

(Berlin), a quarterly.

In 1901-1903 the British Museum published the

catalog of the 35,000 bookplates collected by Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks

(1826-97).

Bookplates, of which there are probably far more

than a million extant examples worldwide, have become objects of collection. One

of the first known English collectors was a Miss Maria Jenkins of Clifton,

Bristol, who was active in the field during the second quarter of the 19th

century. Her bookplates were later incorporated into the collection of

Joseph Jackson Howard.

Some collectors attempt to acquire plates of all

kinds (for example, the collection of Irene Dwen Andrews Pace, now at Yale

University, comprising 250,000 items). Other collectors prefer to concentrate on

bookplates in special fields—for example, coats of arms, pictures of ships,

erotic plates, chess pieces, legal symbols, scientific instruments, signed

plates, proof-plates, dated plates, plates of celebrities, or designs by certain

artists.

Contemporary bookplates and their collection

Since the 1950s, there has been a renewed

interest in the collection of bookplates and in many ways a reorientation of

this interest. There are still substantial numbers of collectors for whom the

study of bookplates spanning 500 years is a fascinating source of historical,

artistic and socio-cultural interest. They have however been joined by a now

dominant group of new collectors whose interest is more than anything the

constitution - at quite reasonable cost - of a miniature, personalized art-print

collection. In this miniature art museum, they gather together the works of

their favorite artists. They commission numbered and signed editions of

bookplates to their name which are never pasted into books but only serve for

exchange purposes.

More than 50 'national' societies of ex-libris

collectors exist, grouped into an International Federation of Ex-libris

Societies (FISAE) which organizes worldwide congresses every two years.

Source:

Wikipedia