|

James Monroe

Fifth President of the United States

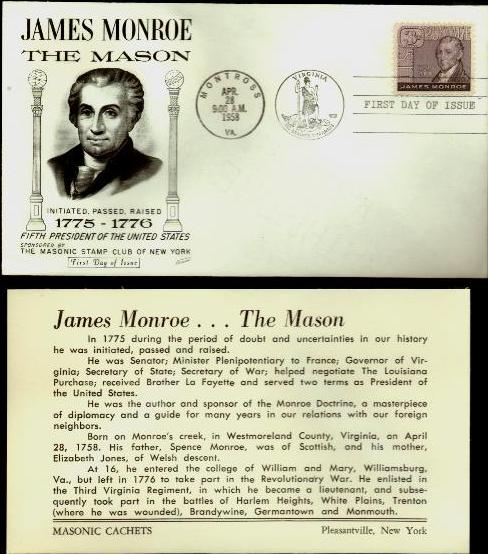

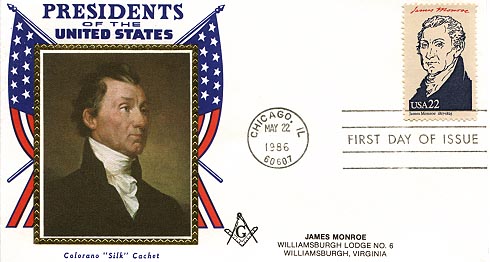

This First Day Cover was sponsored by the

Masonic Stamp Club of New York and was cancelled on April 28th, 1958 in Montross,

Virginia. It is listed in the Scott catalog as number 1105 and 326,988 were made.

On New Year's Day, 1825, at the

last of his annual White House receptions, President James Monroe made a

pleasing impression upon a Virginia lady who shook his hand:

"He is tall and well formed.

His dress plain and in the old style.... His manner was quiet and dignified.

From the frank, honest expression of his eye ... I think he well deserves the

encomium passed upon him by the great Jefferson, who said, 'Monroe was so honest

that if you turned his soul inside out there would not be a spot on it.'

"

Born in Westmoreland County,

Virginia, in 1758, Monroe attended the College of William and Mary, fought with

distinction in the Continental Army, and practiced law in Fredericksburg,

Virginia.

As a youthful politician, he joined the anti-Federalists in the Virginia

Convention which ratified the Constitution, and in 1790, an advocate of

Jeffersonian policies, was elected United States Senator. As Minister to

France in 1794-1796, he displayed strong sympathies for the French cause; later,

with Robert R. Livingston, he helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase. His

ambition and energy, together with the backing of President Madison, made him

the Republican choice for the Presidency in 1816. With little Federalist

opposition, he easily won re-election in 1820. Monroe made unusually

strong Cabinet choices, naming a Southerner, John C. Calhoun, as Secretary of

War, and a northerner, John Quincy Adams, as Secretary of State. Only Henry

Clay's refusal kept Monroe from adding an outstanding Westerner. Early in

his administration, Monroe undertook a goodwill tour. At Boston, his visit was

hailed as the beginning of an "Era of Good Feelings." Unfortunately

these "good feelings" did not endure, although Monroe, his popularity

undiminished, followed nationalist policies. Across the facade of nationalism,

ugly sectional cracks appeared. A painful economic depression undoubtedly

increased the dismay of the people of the Missouri Territory in 1819 when their

application for admission to the Union as a slave state failed. An amended bill

for gradually eliminating slavery in Missouri precipitated two years of bitter

debate in Congress. The Missouri Compromise bill resolved the struggle, pairing

Missouri as a slave state with Maine, a free state, and barring slavery north

and west of Missouri forever. In foreign affairs Monroe proclaimed

the fundamental policy that bears his name, responding to the threat that the

more conservative governments in Europe might try to aid Spain in winning back

her former Latin American colonies. Monroe did not begin formally to recognize

the young sister republics until 1822, after ascertaining that Congress would

vote appropriations for diplomatic missions. He and Secretary of State John

Quincy Adams wished to avoid trouble with Spain until it had ceded the Floridas,

as was done in 1821. Great Britain, with its powerful navy, also opposed

reconquest of Latin America and suggested that the United States join in

proclaiming "hands off." Ex-Presidents Jefferson and Madison counseled

Monroe to accept the offer, but Secretary Adams advised, "It would be more

candid ... to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come

in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war." Monroe

accepted Adams's advice. Not only must Latin America be left alone, he warned,

but also Russia must not encroach southward on the Pacific coast. ". . .

the American continents," he stated, "by the free and independent

condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be

considered as subjects for future colonization by any European Power." Some

20 years after Monroe died in 1831, this became known as the Monroe Doctrine.

|