Issac Newton's Studies of the Temple of Solomon

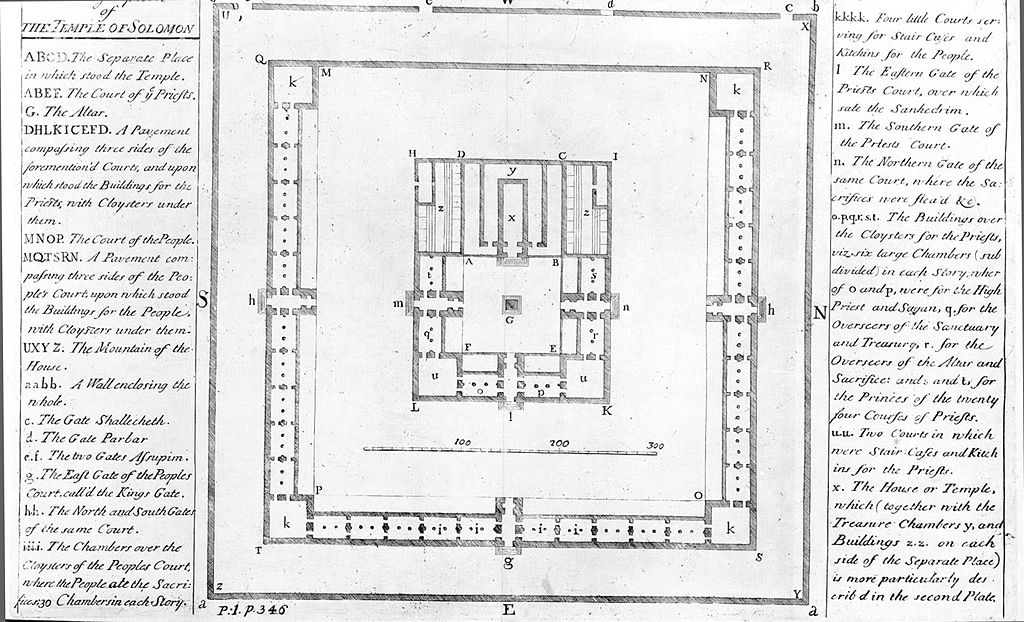

Isaac Newton's diagram of part of the Temple of Solomon, taken from Plate 1 of The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms. Published London, 1728.

Newton studied and wrote extensively upon the Temple of Solomon, dedicating an entire chapter of "The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms" to his observations regarding the temple. Newton's primary source for information was the description of the structure given within 1 Kings of the Hebrew Bible, which he translated himself from the original Hebrew.

In addition to scripture, Newton also relied upon various ancient and contemporary sources while studying the temple. He believed that many ancient sources were endowed with sacred wisdom and that the proportions of many of their temples were in themselves sacred. This belief would lead Newton to examine many architectural works of Hellenistic Greece, as well as Roman sources such as Vitruvius, in a search for their occult knowledge. This concept, often termed "prisca sapientia" (sacred wisdom), was a common belief of many scholars during Newton's lifetime.

A more contemporary source for Newton's studies of the temple was Juan Bautista Villalpando, who just a few decades earlier had published an influential manuscript entitled, "Ezechielem Explanationes", in which Villalpando comments on the visions of the biblical prophet Ezekiel, including within this work his own interpretations and elaborate reconstructions of Solomon's Temple. In its time, Villalpando's work on the temple produced a great deal of interest throughout Europe and had a significant impact upon later architects and scholars.

As a Bible scholar, Newton was initially interested in the sacred geometry of Solomon's Temple, such as golden sections, conic sections, spirals, orthographic projection, and other harmonious constructions, but he also believed that the dimensions and proportions represented more. He noted that the temple's measurements given in the Bible are mathematical problems, related to solutions for Pi and the volume of a hemisphere,

, and in a larger sense that they were references to the size of the Earth and man's place and proportion to it.

Newton believed that the temple was designed by King Solomon with privileged eyes and divine guidance. To Newton, the geometry of the temple represented more than a mathematical blueprint, it also provided a time-frame chronology of Hebrew history. It was for this reason that he included a chapter devoted to the temple within "The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms", a section which initially may seem unrelated to the historical nature of the book as a whole.

Newton felt that just as the writings of ancient philosophers, scholars, and Biblical figures contained within them unknown sacred wisdom, the same was true of their architecture. He believed that these men had hidden their knowledge in a complex code of symbolic and mathematical language that, when deciphered, would reveal an unknown knowledge of how nature works.

In 1675 Newton annotated a copy of "Manna - a disquisition of the nature of alchemy", an anonymous treatise which had been given to him by his fellow scholar Ezekiel Foxcroft. In his annotation Newton reflected upon his reasons for examining Solomon's Temple by writing:

“ This philosophy, both speculative and active, is not only to be found in the volume of nature, but also in the sacred scriptures, as in Genesis, Job, Psalms, Isaiah and others. In the knowledge of this philosophy, God made Solomon the greatest philosopher in the world. ” During Newton's lifetime, there was great interest in the Temple of Solomon in Europe, due to the success of Villalpando's publications, and augmented by a vogue for detailed engravings and physical models presented in various galleries for public viewing. In 1628, Judah Leon Templo produced a model of the temple and surrounding Jerusalem, which was popular in its day. Around 1692, Gerhard Schott produced a highly detailed model of the temple for use in an opera in Hamburg composed by Christian Heinrich Postel. This immense 13-foot-high (4.0 m) and 80-foot-around (24 m) model was later sold in 1725 and was exhibited in London as early as 1723, and then later temporarily installed at the London Royal Exchange from 1729–1730, where it could be viewed for half-a-crown. Sir Isaac Newton's most comprehensive work on the temple, found within "The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms", was published posthumously in 1728, only adding to the public interest in the temple.