Note: This material was scanned into text files for the sole purpose of convenient electronic research. This material is NOT intended as a reproduction of the original volumes. However close the material is to becoming a reproduced work, it should ONLY be regarded as a textual reference. Scanned at Phoenixmasonry by Ralph W. Omholt, PM in June 2007.

THE COLLECTED "PRESTONIAN LECTURES"

1925-1960

(Volume One)

THE COLLECTED PRESTONIAN LECTURES

1925-1960

(Volume One)

Edited by Harry Carr

LONDON

LEWIS Masonic

Quatuor Coronati Lodge

First published in collected form in England in 1965

by

Quatuor Coronati Lodge No 2076

This edition published in 1984 by

LEWIS MASONIC, Terminal House, Shepperton, Middlesex members of the

IAN ALLAN GROUP

Published by kind permission of

The Board of General Purposes of the United Grand Lodge of England

Printed in Great Britain by

Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London

ISBN 0 85318 141 1

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

The Collected Prestonian Lectures 1925-1960 Second edition

1. Freemasons

1. Carr, Harry, 1900-1983 366'.1 HS-395

CONTENTS

Page

List of Illustrations viii

List of Abbreviated References Viii

Introduction ix

Index . 481

1927 Brother William Preston: an Illustration of the Man, his Methods

and his Work Gordon P. G. Hills . 1

1925 The Development of the Trigradal System Lionel Vibert . 31

1926 The Evolution ofthe SecondDegree Lionel Vibert . 47

1928 Masonic Teachers oftheEighteenth Century Dr. John Stokes 63

1929 The Antiquity of our Masonic Legends Roderick H. Baxter 95

1930 The Seven LiberalArtsandSciences H. T. Cart de Lafontaine 121

1931 Medieval Master Masons and their Secrets Rev. Canon W. W.

Covey-Crump 141

1933 The Old Charges in Eighteenth century Masonry Rev. Herbert Poole . 155

1934 The Art, Craft, Science,or `Mistery' of Masonry F. C. C. M. Fighiera 183

1935 Freemasonry and Contemplative Art Walter J. Bunney 195

1936 Freemasonry, Ritual and Ceremonial Lewis Edwards 213

1937 The Inwardness of Masonic Symbolism in the Three Degrees Rev. Joseph Johnson 229

1938 The Mason Word Douglas Knoop 243

1939 Veiled in Allegory and Illustrated by Symbols G. E. W. Bridge 265

1940-6 Lectures suspended during the War years

1947 The Grand Lodge south, of the River Trent Gilbert Y. Johnson 283

1948 The Deluge Fred L. Pick 297

1949 Our Oldest Lodge Col. C. C. Adams 317

1950 Lodes of Instruction, their Origin

and Development W. Ivor Grantham 331

1952 `Free' in `Freemason', and the Idea

of Freedom through six Centuries Bernard E. Jones 363

viii CONTENTS

1953 What is Freemasonry? G. S. Shepherd Jones 377

1954 The Freemason's Education Bruce W. Oliver 385

1955 The Fellowship of Knowledge John R. Rylands 399

1956 The Making of a Mason George S. Draffen . 413

1957 The Transition from Operative to

Speculative Masonry Harry Carr . 421

1958 The Years of Development Norman Rogers 439

1959 The Medieval Organization of

Freemasons' Lodges (Some notes

on Medieval Freemasonry) Rev. Canonj. S. Purvis . 453

1960 The Growth of Freemasonry in

England and Wales since 1717 Sydney Pope . 471

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

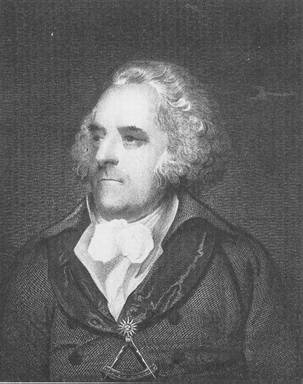

William Preston, as P.M. of the Lodge of Antiquity Frontispiece Page Thomas Ruddiman, Grammarian and Scholar (1674 - 1757) 3

Robert Edward, 9th Lord Petre, Grand Master (Modems) 1772 - 1776 7

James Heseltine, Grand Secretary (Modems) 1769 - 1784. 10

John, 2nd Duke of Montagu, the first Noble Grand Master, 1721 49

William Preston as a young man 62

William Hutchinson, 1732 - 1814, Author of The Spirit of Masonry 73

Diagram: the right-angled triangle . 147

„ the 47th Proposition of Euclid . 149

„ the Tetractys, or the Shem Hamphoresh . 152

Two Sections of the Fortitude MS. of the Old Charges, .c. 1750 173

Nineteenth century Tracing Boards and Symbols 268

Graphs: the Growth of Freemasonry in England and Wales, since 1717 474

LIST OF ABBREVIATED REFERENCES

A.Q.C. Ars Quatuor Coronatorum. Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge.

B. of C. Book of Constitutions.

I.M.A. Installed Masters Association.

M.A.M.R. Manchester Association for Masonic Research. Misc. Lat. Miscellanea Latomorum.

Q.C.A. Quatuor Coronatorum Antigrapha. Masonic Reprints of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge.

INTRODUCTION

EXTRACT FROM THE GRAND LODGE PROCEEDINGS FOR DECEMBER 5TH, 1923.

In the year 1818, Bro. William Preston, a very active Freemason at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries, bequeathed ú300 3 per cent. Consolidated Bank Annuities, the interest of which was to be applied "to some well‑informed Mason to deliver annually a Lecture on the First, Second, or Third Degree of the Order of Masonry according to the system practised in the Lodge of Antiquity" during his Mastership. For a number of years the terms of this bequest were acted upon, but for a long period no such Lecture has been delivered, and the Fund has gradually accumulated, and is now vested in the M.W. the Pro. Grand Master, the Rt. Hon. Lord Ampthill, and W. Bro. Sir Kynaston Studd, P.G.D., as trustees. The Board has had under consideration for some period the desirability of framing a scheme which would enable the Fund to be used to the best advantage; and, in consultation with the Trustees who have given their assent, has now adopted such a scheme, which is given in full in Appendix A [See below], and will be put into operation when the sanction of Grand Lodge has been received.

The Grand Lodge sanction was duly given and the "scheme for the administration of the Prestonian fund" appeared in the Proceedings as follows APPENDIX A SCHEME FOR ADMINISTRATION OF THE PRESTONIAN FUND

1. The Board of General Purposes shall be invited each year to nominate two Brethren of learning and responsibility from whom the Trustees shall appoint the Prestonian Lecturer for the year with power for the Board to subdelegate their power of nomination to the Library, Art, and Publications Committee of the Board, or such other Committee as they think fit.

2. The remuneration of the Lecturer so appointed shall be ú5. 5s. Od. for each Lecture delivered by him together with travelling expenses, if any, not exceeding ú1. 5s. Od., the number of Lectures delivered each year being determined by the income of the fund and the expenses incurred in the way of Lectures and administration.

3. The Lectures shall be delivered in accordance with the terms of the Trust.

x THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

One at least of the Lectures each year shall be delivered in London under the auspices of one or more London Lodges. The nomination of Lodges under whose auspices the Prestonian Lecture shall be delivered shall rest with the Trustees, but with power for one or more Lodges to prefer requests through the Grand Secretary for the Prestonian Lecture to be delivered at a meeting of such Lodge or combined meeting of such Lodges.

4. Having regard to the fact that Bro. William Preston was a member of the Lodge of Antiquity and the original Lectures were delivered under the aegis of that Lodge, it is suggested that the first nomination of a Lodge to arrange for the delivery of the Lecture shall be in favour of the Lodge of Antiquity should that Lodge so desire.

5. Lodges under whose auspices the Prestonian Lecture may be delivered shall be responsible for all the expenses attending the delivery of such Lecture except the Lecturer's Fee.

6. Requests for the delivery of the Prestonian Lecture in Provincial Lodges will be considered by the Trustees who may consult the Board as to the granting or refusal of such consent.

7. Requests from Provincial Lodges shall be made through Provincial Grand Secretaries to the Grand Secretary, and such requests, if granted, will be granted subject to the requesting Provinces making themselves responsible for the provision of a suitable hall in which the Lecture can be delivered, and for the Lecturer's travelling expenses beyond the sum of ú1 5s. Od., and if the Lecturer cannot reasonably get back to his place of abode on the same day, the requesting Province must pay his Hotel expenses or make other proper provision for his accommodation.

8. Provincial Grand Secretaries, in the case of Lectures delivered in the Province, and Secretaries of Lodges under whose auspices the Lecture may be delivered in London, shall report to the Trustees through the Grand Secretary the number in attendance at the Lecture, the manner in which the Lecture was received, and generally as to the proceedings thereat.

9. Master Masons, subscribing members of Lodges, may attend the Lectures, and a fee not exceeding 2s. may be charged for their admission for the purpose of covering expenses.

Thus, after a lapse of some sixty years the Prestonian Lectures were revived, in their new form, and, with the exception of the War period (19401946), a Prestonian Lecturer has been appointed by the Grand Lodge regularly each year.

It is interesting to see that neither of those two extracts announcing the revival of the Prestonian Lectures made any mention of the principal change that had been effected under the revival, a change which is here

INTRODUCTION xi

referred to as their new form. The importance of the new form is that the Lecturer is now permitted to choose his own subject and, apart from certain limitations inherent in the work, he really has a free choice.

Nowadays the official announcement of the appointment of the Prestonian Lecturer usually carries an additional paragraph which lends great weight to the appointment: The Board desires to emphasize the importance of these the only Lectures held under the authority of the Grand Lodge. It is, therefore, hoped that applications for the privilege of having one of these official Lectures will be made only by Lodges which are prepared to afford facilities for all Freemasons in their area, as well as their own members, to participate and thus ensure an attendance worthy of the occasion.

The Prestonian Lecturer has to deliver three "Official" Lectures to Lodges applying for that honour. The "Official" deliveries are usually allocated to one selected Lodge in London and two in the provinces. In addition to these three, the Lecturer generally delivers the same lecture, unofficially, to other Lodges all over the country, and it is customary for printed copies of the Lecture to be sold‑in vast numbers‑for the benefit of one of the Masonic charities selected by the author.

The Prestonian Lectures have the unique distinction, as noted above, that they are the only Lectures given "with the authority of the Grand Lodge". There are also two unusual financial aspects attaching to them. Firstly, that the Lecturer is paid for his services, though the modest fee is not nearly so important as the honour of the appointment.

Secondly, the Lodges which are honoured with the Official deliveries of the Lectures are expected to take special measures for assembling a large audience and, for that reason, they are permitted‑on that occasion onlyto make a small nominal charge for admission.

Of necessity the Lectures are given orally to different kinds of Masonic audience (ranging from ordinary Lodges to Study Circles and prominent Research Lodges). The subjects are usually popular and simple themes, or at least capable of being expressed in clear and uncomplicated language. In three cases within the period covered by this volume (1924‑1960) the Lectures dealt mainly with esoteric matters‑always of the highest interest to the listeners‑but the nature of their contents prevented them from being printed and they are necessarily omitted from this collection. They are: 1924 W.Bro. Capt. C. W. Firebrace, The First Degree P.G.D. 1932 W.Bro. J. Heron Lepper, The Evolution of Masonic P.G.D. Ritual in England in the Eighteenth Century 1951 W.Bro. H. W. Chetwin, Variations in Masonic P.A.G.D.C. Ceremonial xii THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

Despite unavoidable limitations and omissions, the range and scope of the twenty‑six lectures reproduced here is a very ample justification for this unique publication, and the Committee of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge, No. 2076, takes this opportunity of expressing its thanks to the Board of General Purposes for their kind permission to proceed with the work.

The prime reason for a collected edition was because the vast majority of the lectures are out of print. Practically all of them have been published in successive years (usually at the Prestonian Lecturer's expense‑for private circulation) and most of them have appeared at intervals in the Transactions of some of the research Lodges and study groups where the lectures were delivered. In nearly every case, however, the lectures were out of print within a year or two, and even when they are preserved in the printed Transactions, they are only accessible in the larger Masonic Libraries. Yet there is a steady demand for them, both from students working on particular subjects, and for Lodges and study circles who need this kind of material for their research and education programmes. It is hoped, therefore, that the collected edition will prove a valuable aid in every field of Masonic study as well as a stimulus to further work.

Our collection therefore comprises all the Prestonian Lectures from 1925‑1960, inclusive, and the only omissions are those noted above. The choice of the terminal date 1960 was governed partly by the size of the prospective volume, but also because each of the Prestonian Lectures after 1960 has been published in the Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge, and they are, therefore, readily accessible to students.

Treatment of the Texts. The lectures are reproduced here in order of their dates but with one major exception. For the first lecture in the book, we have selected "Brother William Preston: An Illustration of the Man, his Methods and his Work", by Bro. G. P. G. Hills who was the Prestonian Lecturer for 1927. The reasons for this arrangement are twofold. First, because Bro. Hills' lecture was the only one which dealt solely with the life and work of the founder of the Prestonian Lectures, and it has remained to this day by far the best over‑all study of the man and his work, thereby forming a particularly apt introduction to the whole collection.

The second reason was a purely practical one. Throughout the years it became the custom for the Prestonian Lecturers‑whatever their choice of subject ‑to preface their Papers with a biographical sketch of William Preston. Of necessity they all covered the same ground, in more or less detail, and to have reproduced all this repetitive material twenty times or more throughout the book would have been both extravagant and monotonous. By placing Bro. Hills' comprehensive study at the beginning of the book it became possible to eliminate all the biographical Prefaces, and that has been done in every case, except where the Preston references form an integral part of the lecture itself.

INTRODUCTION Xiii

Other editorial emendations may be listed very briefly. Some of the lectures which ran to two or more printings, have appeared with minor variations in the texts. In all cases we have used editorial discretion, but we reproduce only such versions as are known to have been used as Prestonian Lectures. Mis‑spellings and errors of punctuation have been corrected; the excessive use of initial capitals has been curbed; quotations, often carelessly copied or printed, have been checked wherever practicable and corrected where necessary. Charts or diagrams appearing in the original texts have been reproduced exactly, and the Frontispiece and several illustrations have been added which did not appear in the original Papers.

In a few instances (e.g. Bro. L. Vibert's Lecture for 1926) certain brief portions of the text were unsuitable for printing; in such cases the lectures were recast by their authors for the purpose of their first publication, and our reproduction has followed those texts.

The statements, theories and opinions expressed in the lectures are of course those of the authors, and wherever possible, the versions used for this publication have been prepared and corrected by them.

Most of the eminent writers honoured by Grand Lodge appointment as Prestonian Lecturers have been, and are, Brethren who have distinguished themselves in all branches of Masonic activity, and whose Masonic ranks and titles might easily fill several lines of print. In most cases we have quoted only the principal ranks given on the original prints of their lectures. Many of the lecturers were, and are, Past Masters of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge (either before or after their year as Prestonian Lecturer), and in the majority of cases that title alone has been used in conjunction with the holder's Rank. ‑ The collection as a whole, and the individual Lectures, are copyright. All precautions have been taken to obtain permission of the Lecturers (or their heirs) for this publication, and the help which the Quatuor Coronati Lodge has received in this respect from all concerned, is here gratefully acknowledged. All the Lectures are freely available to Lodges, study groups and individual Brethren for use as Lectures to regular Masonic bodies, but reproduction in print‑either in whole or in part may not be undertaken without proper permission.

H. CARR.

London, October, 1965.

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON: AN ILLUSTRATION OF THE MAN, HIS METHODS AND HIS WORK (THE PRESTONIAN LECTURE FOR 1927)

BRO. GORDON P. G. HILLS P.M.

Quatuor Coronati Lodge, No. 2076; P.A.G.Supt. Works Librarian to Grand Lodge

Let me preface my address by an illustration of Brother Preston's character: At the most hopeless hour of his Masonic career, when, as a consequence of his championship of the immemorial rights of the Lodge of Antiquity, Brother Preston had been expelled by Grand Lodge, yet all the same he wrote: "To the institution of Masonry, I shall ever bear a warm and unfeigned attachment; I know its value, and I am convinced of its utility. To the Society of Free Masons I profess myself a true and stedfast friend." Ten years later came a reinstatement equally honourable to all parties concerned, and when at last after many more years happily devoted to the service of the Craft that useful life was closed, it was found that Brother Preston had left handsome legacies as pledges of his lasting attachment to the institution, including the foundation of the Prestonian Lectureship, in perpetuation of which I have the honour to address you this evening.

So Brethren I now claim your attention whilst I endeavour to outline within the limits of a lecture, what the personality of Brother William Preston means for the Craft by an attempt to illustrate the Man, his Methods, and his Work.

Our chief sources of information are Brother Preston's own writings, and the biographical notes of that sincere friend and admirer, Brother Stephen Jones, from both of which sources I shall quote at length.

We have besides much information made readily accessible in two handsome volumes of history of the Lodge of Antiquity, in which Brother Capt. Firebrace has furnished a worthy sequel to Brother Rylands' labours. To researches bearing on the subject by Brothers Hextall and Wonnacott,

2 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

both now lost to us as all Masonic students must deplore, I feel special obligation. To Brother Songhurst, whose ever ready help enabled me to borrow so many rare volumes from our Quatuor Coronati Library, and to my colleague Brother Makins, who so readily helped me to the treasures of the Grand Lodge Library, I am also much indebted and grateful thanks must be offered.

William Preston was born at Edinburgh on July 20th, 1742 (O.S.), the second son and only surviving child of William Preston, Writer to the Signet, in practice in that City. The father, blessed with the advantage of a liberal education, a good Greek and Latin scholar, and credited by his friends with some poetical facility, had attained a recognized position in his profession. As one might expect, special care was devoted to the education of the son. We are told that "in order to improve his memory (a faculty which has been of infinite advantage to him through life) the boy was taught when only in his fourth year, some lines of Anacreon in the original Greek, which he was encouraged to recite for the amusement of his father's friends, when the novelty of this performance was enhanced by the fact that it did not imply that the young genius understood with what wonderful accuracy he uttered." At the early age of six young Preston is said to have made such progress in his English education as enabled him to be entered at the Edinburgh High School, where he made considerable progress in the Latin tongue. Thence he proceeded to College and was taught the rudiments of Greek.

Whilst at the University his studious habits and aptitude attracted the attention of Mr. Thomas Ruddiman, then looked upon as Scotland's representative scholar, who owing to blindness needed an assistant in his work, and he left College to take up the duties of an amanuensis to this gentleman, to whose guardianship he was consigned on the‑death of his father in 1751. The loss of considerable property in Edinburgh through the mismanagement of Trustees, and becoming involved in difficulties through his attachment to friends who had espoused the Stuart Cause in 1745, brought about reverses of fortune and ill‑health which led to the death of the elder William Preston. Ruddiman, too, had similar political leanings, but he satisfactorily weathered the stress of that crisis.

Young Preston was apprenticed to his patron's brother, Walter Ruddiman, partner in their printing firm in Edinburgh, but spent the greater part of his term of articles in assisting Mr. Thomas Ruddiman. This was a great advantage and extension of his educational opportunities, as he was employed in reading to the blind scholar, transcribing works not yet complete and correcting those in the press. These occupations prevented him from making great proficiency in the practical branch of his calling, but after Mr. Ruddiman's death he went into the office and worked as a compositor for about twelve months, during which time he finished a neat Latin edition of Thomas i Kempis (in 18mo), and an edition of Ruddiman's standard work, the Rudiments of the Latin Tongue, whilst his literary abilities were further

4 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

exhibited in a catalogue which he prepared of his friend's library under the title Bibliotheca Romana.

Thus equipped by birth and education William Preston proceeded to London in 1760 furnished with letters of recommendation and introduction from his master and other friends to those who would be likely to help him to start a career in the southern metropolis. Here good fortune attended him, for on presenting his credentials to his compatriot Mr. William Strahan, the King's Printer, he promptly found employment in that printing firm, a connection maintained to the end of his life. Dr. Johnson, who maintained a cordial friendship with Strahan, said that his was the best printing house in London.

A biographical note in the Freemason's Magazine, March, 1795, refers to him thus: "The uninterrupted health and happiness which accompanied him for half a century in the capital, proves honesty to be the best policy, temperance the greatest luxury, and the essential duties of life its most agreeable amusement." Soon after Preston's arrival in London, a number of Masonic Brethren from Edinburgh desired to found a Lodge under a Constitution from the Grand Lodge of Scotland. They were informed that this could not be done, as it would be an infringement of the rights of the English Grand Lodge, but the petitioners were referred to the Antients' Grand Lodge in London. This body granted the Brethren a dispensation to meet as a Lodge, and William Preston was their second initiate, probably at a Meeting on April 20th, 1763, held at the White Hart in the Strand, when the Lodge was formally constituted by the Grand Officers and became No. 111 on the roll of the Antients. Brother Preston and some other members, dissatisfied with the status of their governing body, soon became members of a Lodge meeting at the Talbot Inn, in the Strand, under the other Grand Lodge of England, and prevailed on their friends of No. 111 of the Antients to transfer their allegiance to the older Grand Lodge. So, under the Grand Mastership of Lord Blaney and for a second time, on November 15th, 1764, the Lodge was constituted in ample form as No. 325 "the Caledonian Lodge", under which name it flourishes as No. 134 on the roll of Grand Lodge to this day.

Brother Stephen Jones tells us that circumstances combined to lead Brother Preston to turn his attention to the Masonic Lectures; and explains how, to arrive at the depths of the Science, short of which he did not mean to stop, he spared neither pains nor expense. "Wherever instruction could be acquired, thither he directed his course, and with the advantage of a retentive memory, and an extensive Masonic connection, added to a diligent literary research, he so far succeeded in his purpose as to become a competent Master of the subject. To increase the knowledge he had acquired, he solicited the company and conversation of the most experienced Masons from foreign

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 5

countries, and in the course of a literary correspondence with the Fraternity at home and abroad, made such progress in the Mysteries of the Art, as to become very useful in the connections he had formed. He has frequently been heard to say that, in the ardour of his enquiries he has explored the abodes of poverty and wretchedness, and, when it might have been least expected, acquired very valuable scraps of information. The poor Brother in return, we are assured, had no cause to think his time or talents ill bestowed".

Brother Preston used to meet with his friends once or twice a week, in order to illustrate his version of the lectures; on which occasions objections were started, and explanations given for the purpose of mutual improvement. At last, with the assistance of some zealous friends, he was enabled to arrange and digest to his satisfaction the whole of the First Lecture.

Arrived at this stage in 1772 he organized a Gala Meeting in order to submit the work to the approbation of the Grand Officers and leaders of the Craft. An Oration which he delivered on this occasion was so well received that he determined to print it, and with a description of the proceedings and other matter this formed the first edition of his Illustrations of Masonry, which was published the same year. Encouraged by the successful reception of this first venture our Brother proceeded with his plans to complete the Lectures for the three Degrees.

Having accomplished this, proposals were issued for their delivery as public Lectures to the Craft, which took place at the Mitre Tavern, Fleet Street, during 1774. In further support of these revised workings a pamphlet was issued, entitled "Private Lectures on Masonry by William Preston", giving an account of the Three Lectures which, very slightly elaborated, formed the leading matter of the Second Edition of the Illustrations of Masonry published the next year (1775). Meanwhile in this prospectus, through the medium of the preliminary remarks addressed to the Encouragers and Promoters of Free Masonry, he presented his ideals and objects to the following effect: "No Society ever subsisted which was raised on a better principle or more solid foundation than Free‑Masonry ... It is indeed true, that in some Lodges the WORK of MASONRY is much neglected, and little or no regard shown to the fundamental principles of the Society; arising partly from the inexperience and partly from the inability of those Brethren who have the honour to preside over them ... Thus MEN of LETTERS have been discouraged from pursuing a study which might otherwise have proved of public utility; by giving sanction to the Society, and employing their genius in the elucidation of Mysteries, the greatest Monarchs have not been ashamed to countenance.

As the neglect is owing, in a great measure to a want of method, which a little application might easily remedy, Brother Preston is

5 6 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

induced to offer his assistance to ALL REGULAR MASONS desirous of making a progress in the Art ... If Brother Preston succeeds in his expectations of giving his Brethren a just idea of Masonry, or promoting an uniformity in the Lodges under the English Constitution, he will be perfectly happy in the attempt he has made, and will spare no pains faithfully to fulfil his engagements with every gentleman who is inclined to encourage his design".

Annexed were the following CONDITIONS.

I. Every Degree to consist of Twelve Courses.

II. One guinea to be paid on admission into every Degree.

III. Any Brother not perfect in any one Degree at the expiration of the Twelve Courses, shall have the privilege of attending six more, without any additional expence.

IV. Books of the Courses will be given to every Brother at the com mencement of his instructions.

V. Instructions will be given Three times a week at an appointed hour.

I have already explained that Brother Preston's book Illustrations of Masonry took its rise from the Grand Gala Performance of the First Lecture on May 21st, 1772.

The first edition of the book differs very considerably from its many successors and is now a very rare volume. The title page bears the following lines by Dr. Blacklock: The Man whose mind on virtue bent Pursues some greatly good intent, With undiverted aim; Serene beholds the angry croud Nor can their clamours fierce and loud, His stubborn honor tame.

The quotation is wonderfully apt under the circumstances for already, as Preston himself wrote, the methods adopted had excited in some "an absolute dislike" of what they considered as innovations, and in others "a jealousy" which the principles of Masonry ought to have checked.

The volume bore the imprimatur of Grand Lodge over the signatures of the Grand Master Lord Petre, Deputy Grand Master, Wardens and Secretary.

In the Preface it is explained that the first design was only to publish the Oration delivered at the Gala, but the entertainment being to be annually repeated, certain particulars were put on record to serve as a precedent for future exhibitions of the same kind. The plan being thus extended beyond the bounds of a pamphlet, Preston explains: "I resolved to select some of the best

8 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

pieces on the subject I could find; and to annex a few commentaries to answer the end in view. To this was added an Appendix containing many articles never before published, compiled from the most authentic records, and the best authorities I could procure".

The Second Edition of the Illustrations of Masonry appeared in 1775, again with the imprimatur of the Grand Master and his Officers.

In this Edition the particulars of the proceedings at the Grand Gala in 1772 "are entirely omitted to make room for more useful matter", so runs the preface, and from being denominated an "entertainment to be annually repeated", it is put aside "as it was a temporary affair".

The book now commences with "A vindication of Masonry including a Demonstration of its Excellency", which in later editions came to be headed "The Excellency of Masonry displayed"; then follow "Remarks on Masonry including an Illustration of the Lectures", and a great deal of fresh matter especially under the heading of "History of Masonry in England", which carries it from the days of the Druids to the reigning G.M. Lord Petre. Special stress was laid on the Hall building project in which Brother Preston took great interest. Contrary to the usage of Masonic publications of those days, no songs except those sung at the Gala accompanied the First Edition, but "as the description of that performance was now omitted several others which are usually sung in the course of the ceremonies were explained in this Work".

In the form thus arrived at Brother Preston's book achieved its success, and did a great work for the Craft by bringing together scattered matter in a harmonious whole and making it generally available and, by presenting the institution in a dignified and worthy manner, rendered it acceptable even to those who were not members of the Society. There is no doubt it did much to raise the general estimation of Freemasonry, and whilst we must differ from some of its presentments. of history and theory, many useful lessons are inculcated equally applicable to our days. There remains, too, above all an engaging enthusiasm, a genuine love for the order and the Brethren and the spirit pervading it, which is at the very roots of our institution and must ever insure among Masons an affectionate feeling of gratitude to our worthy Brother for his labours.

The book ran through twelve English editions during its author's lifetime, and then, under the editorship of Brother Stephen Jones and finally of Dr. Oliver, reached the seventeenth English issue in 1861. There were published also from 1776 onwards German translations, American re‑issues (1801, etc.) and a Dutch translation as late as 1848, but no French edition seems to have been called for. In the English Craft it was frequently given to initiates, and became an almost indispensable Lodge possession, ranking only after the V.S.L. and the Book of Constitutions. Old copies evidence by their well thumbed condition their constant use for reading the ancient charges at the opening and closing of the Lodge.

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 9

During the Grand Mastership of the Duke of Beaufort (1767‑1771) Brother Preston was employed by the Grand Secretary to assist in arranging the general Regulations of the Craft, and in revising the foreign and country correspondence. This led later on to his being appointed Assistant or Deputy Grand Secretary at a salary of ú20 per annum under Brother Heseltine in 1769. This post did not amount to Grand Office, but Preston's name was associated with those of the Grand Officers as "Printer to the Society"; all the same, he carried on the chief part of the Secretarial correspondence, entered Minutes, attended Committees, completed and corrected the Calendars with the History of Remarkable Occurrences, and prepared an Historical Appendix to the Book of Constitutions as issued in 1776. All this work gave him access to special sources of information which he was able to turn to good account in historical matter introduced in the later editions of his Illustrations.

Brother Preston took an active part in proceedings as a member of the Hall Committee of Grand Lodge, and to this period belong his subscriptions of ú20 to the Hall Fund and the like amount to the Masonic Charity for Girls.

He resigned his Secretarial appointment at Christmas, 1777.

Outside the Craft, Brother Preston prospered in his business as a printer and corrector of the press in connection with Mr. William Strahan's firm, on whose death in 1785 he became recipient of an annuity of ú30 for life and took the position of chief reader and superintendent to the son, Mr. Andrew Strahan, who succeeded to the business. That his literary capacity was considerable is clear. We are told: "His critical skill as a corrector of the press led literary men to submit to the correction of style: and such was the success of William Preston in the construction of language, that the most distinguished among them honoured him with their friendship as presentation copies in his library including such names as Robertson, Hume, Gibbon, Johnson and Blair bore testimony".

Within the craft, as we have seen, Brother Preston had now reached an honoured, or what he would have called a `truly respectable' position, and was known by his various activities to a wide circle as the Order then existed. He attended various Lodges of Instruction to propagate his system. He had already been Master of several Lodges when circumstances, which we must consider in some detail, led him to the Chair of the Lodge of Antiquity.

Among those taking a leading part in assisting Brother Preston at his Gala Performance of the First Degree Lecture in 1772 was Brother John Bottomley, Master of the Grand Stewards Lodge at that time, who was Master of the Lodge of Antiquity from 1771 to 1774, when attendance was very poor and the Lodge in flagging condition. Another member was Brother John Noorthouck, who joining in 1771, was Senior Warden from 1772 to 1774. Brother Bottomley's membership dated back to 1768.

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON

Brother Noorthouck, the son of a well known London bookseller of Dutch origin, was in a very similar walk of life to Brother Preston, in fact, like him largely in the employment of the Strahans, and a few years later to be the recipient of an annuity of ú20 on the elder Strahan's death, when ú30 a year was left to "my present Overseer" William Preston.

These two Brethren, Bottomley and Noorthouck, conceived the idea of introducing Brother Preston into the Lodge of Antiquity to retrieve its fortunes by his activities and zeal.

Brother Preston appears already to have attended a Meeting of the Lodge of Antiquity in February, 1772, as a visitor hailing from the Lodge of Prosperity, when on March 2nd, 1774, he was proposed as a joining Member. He was duly elected a Member on June 1st, when he was not, however, present, and so was not, as often stated, elected a member and the Master of the Lodge on the same day. It was at the following Meeting of Antiquity on June the 15th that he made his first attendance as a Member and was honoured by election to the Chair.

Under Preston's Mastership the prosperity of the Lodge was rapidly restored. He was greatly impressed with the importance of his position as Master of the first Lodge under the English Constitution and threw himself heart and soul into the work in what he conceived to be the best interests of the Lodge. He studied its past records and tried to establish a position by which the fullest prerogatives of a Lodge acting by immemorial constitution might be preserved intact under its allegiance to Grand Lodge. Unfortunately, the activities of this new member did not meet with the approbation of the very men who had been responsible for his introduction, and when the discontent of their party within and without the Lodge had developed into an attack upon Brother Preston, we find Brother Noorthouck writing to complain that "Brother Preston after being not only admitted but honour'd with the Master's Chair, crouded in such a succession of young masons, as totally transferred all the power of the Lodge to him and his new acquaintance and enabled him to keep possession of the Master's Chair for three years and a half ... During this time Bror. Preston kept up private weekly meetings of these young Brethren, under the name of a Lodge of Instruction, in which meetings, he occasionally as your memorialists have been informed propagated matters of peculiar original powers residing in their Lodge, exempt from the authority of the Grand Lodge, pretensions of which your Memorialists and the other Old Members of the Lodge never before entertain'd any idea . . ." It strikes one as less than generous that Brother Preston should be blamed for holding the Mastership during a period of three and a half happy and prosperous years when his predecessor, Brother Bottomley, had occupied the Chair for an exactly similar period under the depressed circumstances then

12 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

prevailing in the Lodge. Brother Noorthouck's version of the proceedings speaks for itself, and it is amusing to note that he evidently did not attend the Lodge of Instruction as its procedure was only hearsay to him and his friends. That the lectures were not to his taste may be clearly illustrated from his letter to the Master, Brother Preston's successor, at this crisis, in which he wrote: "I am but a dull and awkward schoolboy in my responses, but nevertheless I claim some LITTLE acquaintance with the PRINCIPLES of the Order: and these reach beyond the meer catechisms, which require only a disengaged mind with a retentive memory".

Evidently Brother Preston's working of the lectures and powers of memory annoyed Brother Noorthouck.

At a Meeting in October, 1776, Preston received the thanks of the Lodge because he had maintained the precedence of the Lodge of Antiquity No. 1 at a Lodge he had visited, where it had been challenged by a member of the Stewards Lodge, then No. 60. Brother Bottomley's opinion as a P.G.Stwd. does not appear.

We can gather, then, there was a current of dissension inside and outside the Lodge waiting only for an opportunity to get vent. The pretext arose when some of the Brethren of the Lodge went to St. Dunstan's Church, Fleet Street, to celebrate St. John's Day, December 27th, 1777, by hearing a sermon by their Chaplain. They put on their Masonic Clothing in the Vestry and sat together in the same pew; one, at any rate, Preston by his own account, arrived late, and put on his Masonic Clothing when he had entered the reserved pew. It was only a few steps across the street to the quarters of the Lodge at the Mitre Tavern, as the Church then projected into the road considerably to the South of its present position, and so, after the service, the Master queried should they take off their clothing or wear it across to the tavern ? Preston tells us that he said, "I should certainly, I was not ashamed of it, I was then invested and should not divest myself till the business of the day was finished ... We accordingly returned to the tavern in jewels and clothing as representatives of the Lodge, preceded by the Beadles but without any formal procession as Masons".

Brothers Noorthouck and Bottomley were not present, but they and their friends alleged that the proceedings constituted a public procession of Masons in their Clothing, and made this the subject of complaint to Grand Lodge. Unfortunately, Brother Preston attempted to justify what at the worst was a mere error of judgment by pleading inherent rights peculiar to the Lodge of Antiquity. I must not now attempt to set out the history of what followed; to do it adequately and to do justice to all concerned makes a long story and by no means a pleasant one, and has quite as much to do with the history of the Lodge, in whose records it may be followed, as with our Brother. It is with Brother Preston that we are now dealing, and to put the matter briefly I would say that there is no room for doubt that he was very hardly and unfairly treated. It was for his championship of the Lodge rights, as he

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 13

conceived them, that he suffered; for himself he had no consideration, he was simply determined that he would not be a party to betraying the trust of those immemorial privileges. All the same, his theory was incompatible with allegiance to the Grand Lodge, as the sequel clearly demonstrated.

Procedure and forms were strained against Preston and his supporters, and at last, on January 29th, 1779, they were expelled by Grand Lodge. Yet worse was to follow, for by their action in carrying on the Lodge independently and in alliance with the Grand Lodge of All England at York, and yet further by forming themselves into a new Grand Lodge for England South of the River Trent, the offenders seemed to have put themselves hopelessly beyond any chance of future reconciliation.

The two parties of the Lodge of Antiquity pursued their several ways, and Brother Preston summed up his version of the affair in a pamphlet dated June 3rd, 1778, and entitled, "State of Facts", in which, despite his recent harsh treatment, occur those memorable words which I quoted at the commencement of my lecture: "To the institution of Masonry, I shall ever bear a warm and unfeigned attachment. I know its value and I am convinced of its utility. To the Society of Free Masons I profess myself a true and stedfast friend".

In his statement Brother Preston claims to have introduced as many as three hundred initiates into the Order, and proceeds: "I have been employed upwards of fourteen years in establishing a system for the honour of the Society, in the course of which I have consulted the best authors, ancient and modem. I have now in my possession extracts from above two thousand volumes on the subject. These I intend to arrange under the title Adversaria, and publish under sanction, with a few cursory observations; but the present dispute I believe has effectually baffled my intention". Another "work I have long had in contemplation" was "A Digest of all the laws which have subsisted since the establishment of the Grand Lodge". A very unfriendly pamphlet on the other side, Masonic Anecdotes of little Solomon: a Caution to the Fraternity, appeared about 1788.

Our Brother took part in the activities of his section of the Lodge of Antiquity and in the brief existence of the newly constituted Grand Lodge for the South, yet evidently the turn of affairs had come as a heavy blow and disappointment. In fact, at one time he even determined to bid "a complete Adieu to the Society". Hence we find that he had not attended the Lodge for over a year when on October l7th,1781, his resignation was tendered, and in other respects his Masonic activities were in abeyance, so that, as his biographer quaintly comments, he was enabled "to direct his attention to his other literary pursuits which may fairly be supposed to have contributed more to the advantage of his fortune".

14

Meanwhile, the Lodge got into very low water, but at length the earnest entreaties of his friends and doubtless the warm interest he had felt in the Lodge prevailed on him to rejoin. This was on October 23rd, 1786, and for a second time Antiquity was revived by the accession of Brother Preston to its ranks.

This renewed interest in the Craft led to the organization of a special scheme by which Brother Preston determined to propagate his System of Lectures ‑ the so‑called "revival" of the Antient and Venerable Order of Harodim, which was, in effect, a dignified Lodge of Instruction to render his Lectures, inaugurated by a Meeting at the Mitre Tavern, Fleet Street, on January 4th, 1787.

The Lodge of Antiquity adhering to the Grand Lodge passed through its vicissitudes, but when, at a Meeting on December 2nd, 1789, we find Brother Preston attending as a visitor, a happy ending to the division was in view, for Preston and his friends, having made an apology to Grand Lodge "signifying their concern that through misrepresentation they should have incurred the displeasure of Grand Lodge ... to the Laws of which they were ready to conform", had only a month since been reinstated and restored to their privileges in Masonry, as Preston himself acknowledged, "in the most handsome manner". Following this, in November, 1790, the reunion of the two Sections of the Lodge of Antiquity was most auspiciously accomplished.

In our survey of Brother Preston's career to this point we have reviewed some of his work and touched upon many of his methods in general, but I will now consider a little further in detail what is recorded of his own presentation of the lectures and their matter.

From his own account of the manner in which the first Lecture was rendered at the Grand Gala in 1772 we can see that he spared no trouble to make the ceremony as impressive as he could, and the musical accessories both vocal and instrumental‑are particularly worthy of attention. The first edition of the Illustrations gives full particulars with a plan of the room which indicates besides the ceremonial arrangements an ample table accommodation for the liquid refreshment wherewith the toasts were duly honoured.

The Lodge was opened in due form by command of the G.M. in the Chair, Brother Preston officiating as Master.

The S.W. rehearsed the Antient Charges on the Management of the Craft in Working and then read Laws for the Government of the Craft, followed by the Toast.

THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES

Brother Preston delivered his Oration, thus laying the foundation stone of his future Illustrations of Masonry.

Toast. The GRAND MASTER‑flourish with Horns.

The Six Sections of the first Lecture were then rehearsed accompanied by songs and duets and instrumental music with the appropriate toasts.

"The King and the Craft", which was honoured by a "Flourish of Horns".

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 15 At the Close of Section VI., The Charge on the Behaviour of Masons was rehearsed by Brother Preston, and then came the Toast. May the cardinal virtues with the grand principles of Masonry always distinguish us; may we be happy to meet, happy to part, and happy to meet again, followed by the Entered Apprentice's Song, the first verse, altered to a rather more dignified form for the occasion: Come let us prepare, We brothers that are Assembled on noble occasion: Let's be happy and sing, For Life is a Spring To a Free and an Accepted Mason.

Then, Brother Preston records, "the Grand Master in the Chair expressed his great approbation of the regularity of the whole proceedings." "The Lodge was closed and the Grand Officers preceded by the Stewards for the occasion, and attended by several respectable personages adjourned to supper, an elegant entertainment being provided at the expense of the Stewards, and the evening was concluded with the greatest joy and festivity". There was, of course, no novelty in Lectures or the use of catechism, which in days before books were available had been the only means for imparting general instruction in the Arts and Sciences. The old methods by which the Speculative or theoretical side of the Craft had been taught, survived in the Lodge "Work", though, as the exposures demonstrate, much degenerated and fast approaching a mere residuum of tests and catch words. There were also addresses, charges, eulogies such as were connected with the names of Bros. Oakley, Martin Clare, Dunckerley, Edmondes, Wellins Calcott and many others. Lectures on Architecture and Geometry, Science and other interesting subjects, were given in Lodges in which there were members of intellectual attainments.

The prevalence of such customs is confirmed by strictures of the pugnacious Grand Secretary of the Antients in his Ahiman Rezon (1764) at this date, where he complains that, amongst the degenerate Modems, the old custom of studying Geometry in the Lodge was likely to give way to the use over proper materials of a good knife and fork in the hands of a dextrous brother, and the use of the globes might be taught and explained, amongst the degenerate Modems, as clearly and briefly upon two bottles as upon Mr. Senex's globes of 28 inches diameter.

The Minutes of the Lodge of Antiquity from 1756 onwards record Lectures in various Degrees as when (1757) "The Master gave an Extraordinary joyous lecture" or (1762) when "The R.W.M. was pleased to favour 16 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES us with a Noble Lecture in the Third Degree" or that of the First (1763) "was given in a most Excellent & Explicit manner", which might be paralleled by extracts from many other old Minute Books.

Brother Preston did not invent lectures, but he carried on the old traditions, endeavouring to correct, refine and amplify the old workings, welding together lectures, addresses, eulogies, in a complete system according to his method.

The Minutes of the Lodge of Antiquity record a performance of the Lecture of the Third Degree with musical accompaniments on a scale similar to the setting of the first Lecture. In this case, however, Brother Preston officiated as Chief Ruler and was supported by his S. and J. Wardens as Senior and Junior Rulers.

To Brethren who have not studied the subject the names of the leading Officers may suggest a further step beyond the Third Degree, but in the ancient working as carried on by the Lodge of Antiquity and exemplified at the Lodge of Promulgation and by its propaganda, so soon as the Brethren have proved themselves Craftsmen the principal officers become for that, and for the higher Degree, a Chief Ruler and Senior and Junior Assistant Rulers instead of Master and Wardens. These usages disappeared under the workings of the Lodge of Reconciliation.

This is the only record of this elaborated ceremony being worked that occurs in the Minutes of Antiquity.

Neither Brother Bottomley nor Brother Noorthouck were present.

It was when, encouraged by his friends, Brother Preston determined to resume his Masonic activity that his Lectures received the full elaboration of their setting in the Harodim Chapter method. Our Brother is said to have "revived" the Antient and Venerable Order of Harodim, that is of Harods or Rulers, but we have yet to determine its origin, possibly the ceremony of being "made free from Harodim", still nominally in existence, may point to a source, but I must leave that issue aside for the present, nor can I dwell upon the details of its organization, which are set out in full detail in the Plan and Regulations of the Grand Order of Harodim printed in 1791. It was described by an ardent supporter as an "institution which certainly claims respect and deserves encouragement; inasmuch as, while it preserves all the ancient purity of the Science, it refines the vehicle by which it is conveyed to the ear; as a diamond is not less a diamond but is enhanced in its value, by being polished".

The Harodim Chapter died out about 1801, having served its purpose as a means of propagating Brother Preston's version of the Lectures which at that period were regularly worked in the Lodge of Instruction attached to the Lodge of Antiquity and illustrated at the Lodge Meetings.

It remains for me briefly to outline what these famous lectures were. Preston's own Lectures necessarily cover very much the ground of those with which we are familiar today, but there is a good deal of difference in BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 17 Thus we define the friendly salutations we intrust amongst Masons, and thus we demonstrate this truth‑That from the eyes of Masons the beauties of Heaven are never screened.

Clause 5 defines the key which opens our Treasures and which every faithful Brother bears with him.

SECTION II. in six Clauses carries the Initiate from preparation to the end of the Obligation:‑ the verbiage and the order of the matter, and there are besides considerable portions which have no exact counterparts today.

The First Lecture consists of Six Sections, the Second of Four, and the Third Lecture is prolonged to no less than Twelve Sections. Each Section is further sub‑divided into Clauses.

The three Lectures are each of them prefaced by preliminary dissertations‑paragraphs which were published in the Illustrations and which appear in print in connection with workings of the lectures in vogue today.

After such introduction the first lecture starts in the usual method of question and answer, and we are taught: That a Mason is never too wise to leam‑that the wise seek knowledge and more travel to find it from West to East.

The Master is placed in the East.

Because it ever has been, and continues to be, and always shall be the situation of the Master when he. acts in that capacity.

"Why is he placed there?" and further questions elicit: Because Man was there created in the Image of his Maker; there also knowledge and learning originated, and there the arts and Sciences began to flourish . . . Other men may gain knowledge by chance or accident but Masons must acquire it, otherwise they cannot obtain preferment ... the best use is made by Masons because the knowledge they have acquired they will improve to the best advantage, and thence once improved they will evidently dispense it for the general good.

Clauses 2, 3 and 4 deal with familar matter and the last enlarges on the symbolism of the Sun at its various stations The J.W. "placed in the South at high 12 invites the Brethren to the cool shade, there to enjoy rest and refreshment." In the West the Third Grand Natural Object is "still the Sun in a scene equally pleasing setting in the West, closing the day, and lulling as it were all nature to repose".

The Senior Warden renders to every brother the just reward of his merit to enable him to enjoy a comfortable repose, the best effects of honest industry when they are properly applied.

Each Clause ends with a summary such as is appended to this: 18 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES Thus we demonstrate our regular possession of the invaluable and inestimable secrets of Freemasonry and the advantages to be derived from the faithful observance of them.

SECTION III. in six Clauses continues the Ceremony. In Clause 3: The Ancient Clothing of a Mason is described as white gloves and white leather apron, the first denoting Purity and the second Innocence, both considered as the badge of Innocence and the bond of Friendship.

In the next Clause the advantage of laying a foundation stone is explained: That should the ravages of time or violence destroy the whole superstructure, this stone when discovered will prove that such building did exist, the name of its founder, and the purpose of its being erected.

How can this apply to the N.E. comer? Because should the influence of virtue cease to operate amidst the corruption of men and the depravity of manners, the original principles which were impressed on his mind on that spot, will never be obliterated, but will guard him from the dangers of infection and preserve his heart untainted in the general corruption of the world. Clauses 5 and 6 traverse the Master's address to the Candidate and the Charge: Masons live to improve and improve to enjoy. Thus the admiration which is excited by the display of talents and virtues is a pleasing sensation; curiosity is gratified by marking the steps of fortune; the views of men are enlarged by tracing the effects of conduct and the heart is meliorated when it contemplates the principles whence good actions proceed.

In SECTION IV.

Clause 1 refers to the methods of the Egyptians, the great lights. In Clause 2, the form of the Lodge, a parallelogram, is explained.

Clauses 3, 4 and 5 deal with the Site, the situation of the building and its construction, the covering of the building and its supports, leading up to the description of the Mystical Ladder in Clause 6.

In SECTION V.

The first three Clauses explain the internal omaments, the furniture and jewels, the fourth the Dedication of the Lodge, and the two final divisions exemplify matter in the nature of charges.

In SECTION VI.

Clause 1, we learn that we meet on the level and part on the square, and where to find a brother.

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 19 Clauses 2, 3 and 4 deal with Brotherly Love, Relief and Truth, the Cardinal Virtues, and in the final Clause, Day, Night and the Wind in Freemasonry are considered.

The dissertations on Brotherly Love, Relief and Truth which appeared in the Illustrations are familiar to workers of the lectures today.

We are taught with regard to the Master that: The Master should be hailed with homage and respect as Master of the Art, clothed in Royal Robes of blue purple and scarlet, that by this testimony he might display his skill and talent before the world ... With becoming grace he would receive all this ... but the Lodge no sooner formed than he would lay all aside for the Badge of Innocence and Friendship.

THE SECOND LECTURE is divided into FOUR SECTIONS.

The Five Clauses of the First SECTION deal with the Fellow Craft's progress from his preparation till his charge at the S.E. comer of the Lodge. In the Second SECTION, Clause 1 treats of the number of Degrees, the establishment of the Order, qualifications and service.

. In the Second Clause "we define the lodge held and the number of which it was originally composed", and some interesting points arise: The Lodge in the 1st degree is said to be assembled because there is an assembly of all the degrees of the order virtually represented.

The Lodge in the 2nd degree is said to be held because only a deputation from the General Lodge can be authorized to hold such a Lodge, and no Entered Apprentice is there permitted to assemble.

Five are necessary to hold a F.C. Lodge, three M.Ms. and two F.Cs. who represent all the absentees of the 2nd and 3rd Degrees and allude to the division of the Science into five branches and the five years employed in learning the rudiments of these Sciences, which was the time fixed to constitute a F.C.; there is also an allusion to the five senses (seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling and tasting) for they are the channels by which external objects are obtained and like signs in the natural language, have the same significance in all climates, and in all nations.

The Master's place is in the East where he denotes that Wisdom, represented by the column having the light in the East, which was before all things and is over all the works of the Creation.

Clause 3 deals with Geometry.

Clause 4 with The Rise of the Orders [of Architecture]. and the concluding Clause exemplifies the "Five Senses".

The THIRD SECTION includes five Clauses devoted to: 1. Classes at the Temple.

20 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES 2. Periods of labour and division of Time.

3. The two great pillars.

4. The staircase and foundation of the system.

5. The Sacred Symbol at the centre of the Lodge.

The FOURTH SECTION is intended to exemplify the Sciences as symbolized in the Temple; and the five Clauses illustrate: 1. The general description of the Temple.

2. The Temple religiously considered.

3. The Temple morally considered.

4. The Temple scientifically considered leading up to the origin of the present establishment at its building.

Several of these Sections contain a large amount of unfamiliar matter which only quotation at large could do justice to.

The THIRD LECTURE according to Brother Preston's 2nd Edition of the Illustrations consisted of Twelve Sections. Later on its matter seems to have been re‑arranged so as to be comprised under seven Sections. The length of the lecture is to be accounted for by the inclusion of the Installation Ceremony, Consecration of a Lodge and public functions beyond the Legendary History and actual ceremonies of the Degree.

The Working is very ceremonious and slow in development; the main headings must suffice for our present purpose. An introductory Section is succeeded by THE SECOND SECTION, which contains a History of the Order, in seven Clauses, of a very speculative character: 1. History of the corruption of Mankind.

2. Progress of the Institution to remedy or prevent that corruption.

3. Remedies adapted to each of those evils.

4. What types were adopted to teach the nature of our Soul.

5. How (the) System of Society was purified at the building of the Temple.

6. Organization of the Society at the building of the Temple.

7. Explains how the System has been adulterated since that period.

In SECTIONS III. and IV., each of seven Clauses, the History of the Degree is set forth in a method which, while it considerably lengthens the recital, does not materially add to the information.

SECTION V., in seven Clauses, again deals with the Mystery of the Third Degree, the Lodge, Ornaments, Tracing Board, Steps, Circumambulations, fall and raising.

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 21 SECTION VI. treats of the Government of the Society in the Constitution and Consecration of a new Lodge, explanation of the jewels, and Installation of Masters.

SECTION VII. relates to public Ceremonies, the Laying of a Foundation Stone, Dedication of a Masonic Hall, Burial Service of a Mason, with the conclusion of the History of the Third Degree.

And now, with a few more words about our Brother himself, I must bring my remarks to a close.

Brother Preston was for many years Editor of the London Chronicle, and, as has been mentioned, since 1804 a partner in the firm he had served so well. It was said that he might be designated a "pioneer in literature", having conducted through the Press of the house of Strahan some of the most celebrated works of the eighteenth century writers. He certainly was a pioneer in his Masonic work.

An excellent Portrait of Brother Preston in the prime of life was painted by Samuel Drummond and engraved more than once. It appeared in the Freemasons' Magazine of 1795 to illustrate the biographical note by Brother Stephen Jones. This engraving omits the Past Master's jewel of 1778 which appeared in the original; it shows a fine intellectual face with a determined mouth. Another portrait in crayons, which hung in his parlour at the time of his death, depicts him a little softened by time, with a very happy expression, and there is yet another oil painting by Drummond, of which engravings were published‑a very pleasant picture of his later days‑showing him as an old gentleman full of vigour and alertness, of which engravings appeared in the European Magazine, 1811, and in subsequent editions of the Illustrations of Masonry. The originals in the last two cases are in the possession of the Lodge of Antiquity at Freemasons' Hall.

The Lodge also has there a plaster bust founded on a death mask, taken two days after death by Giannelli, of Snow Hill, under the supervision of Brother Sir F. C. Daniel.

Brother Preston's later years in Masonry were bound up with the history of Antiquity which he served so diligently until ill‑health limited his powers. From 1790 he was annually elected Deputy Master, except when another took his place on account of illness in 1802 and 1807, and when in 1809 the Duke of Sussex accepted the Mastership he appointed him his Deputy Master. It was in 1813 that William Preston, Citizen and Stationer, made his Will, when his Masonic bequests of ú500 Consols to the Girls' School, the same amount to the General Charity Fund, and ú300 to found the Presto 'an Lectureship, showed him, as he had professed, the true and steadfast friend of the Craft to the end of his life.

His last attendance at the Lodge of Antiquity was at the Installation Meeting, January 17th, 1816.

22 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES After an illness of nearly five years Brother Preston passed away at his residence, No. 3 Dean Street, Fetter Lane, on April 1st, 1818. The funeral took place at St. Paul's Cathedral, where he was buried on April 10th. An appreciative notice in the Gentleman's Magazine ends by describing the funeral as "of the most handsome description ... In consequence of the rain the Female Orphans belonging to the Freemasons' Charity in St. George's Fields were not able to follow in procession but mustered at the Church under the care of the Treasurer ... and returned to the house of the deceased where they partook of wine and cake".

Let us close with a quotation from a letter which the M.W.G.M. of those days, H.R.H. The Duke of Sussex, addressed to the Lodge of Antiquity in 1813, conveying an appreciation of Brother Preston and a commendation of his example equally applicable for us today: "Long has the Lodge of Antiquity been remarkable for its zeal in Masonry, and greatly is that Lodge and the Craft indebted to the diligence and example of my worthy Brother your Past Master Preston, whose name must be dear to every admirer and well wisher of our ancient Order. I have therefore only to recommend your following his steps, when I may anticipate the most glorious Result".

APPENDIX A DETAILS OF THE RENDERINGS OF THE FIRST AND THIRD LECTURES.

As regards the First Lecture we have the account of the occasion several times referred to of the "Grand Gala in honour of Free Masonry held at the Crown and Anchor Tavern ... on Tuesday the 21st Day of May 1772" fully set out in the First Edition of the Illustrations with a plan of the room, which we may take as situated East and West, which was arranged as follows An oblong room, nearly twice its width in length had a passage way reserved across the West and entered at the South West corner of the room; two L. or square‑shaped tables ranged with their long arms parallel to the Western portions of the North and South walls, and their shorter lengths running across and only leaving room at the centre for a passage way between the ends of the tables‑"The Grand Entrance for the Procession" to the Lodge enclosure. At these tables the rank and file of the Brethren were seated on both sides of the boards. At the further end of the Hall in the East sat the Grand Master "on a Throne, elevated 1' Foot," his Deputy and the Past Grand Master to his left and right with two seats beyond on either side for Past Grand Officers. Opposite the three principal Chairs was "a rich carpet" on which stood "the Pedestal, with the Furniture, Regalia, etc., on a crimson velvet cushion with Gold Tassels".

On either side about in a line with the Pedestal approaching the centre archwise were the Grand Wardens' Chairs supported in each case by six seats, BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 23 three on either hand for "Respectable Personages". Further Westward the walls were lined with a table on each side North and South with six seats at each for the Stewards for the Gala distinguished by their white rods. The centre of the floor space was occupied by the Lodge‑the Lodge Board‑the Master of the Lodge sitting at the centre of the end furthest from the Grand Master‑the West end apparently‑and two Assistants at either of the sides North and South. The East end of the Lodge Board was unoccupied, but along the South side were placed "The Three Great Lights properly elevated", one at the centre and the others at the angles of the Board, South East and South West.

To minister to creature comforts, tables were provided in front of the Wardens and their supporters, and there were stands before the three chief seats specified to be covered like the various tables already mentioned with green baize; there were two side tables "properly furnished" in the North Fast and South East comers of the room, and an enclosure described, "Repository for Wine", occupied the North West comer opposite the entrance. A gallery for Musicians was placed at the South East of the room.

The Lodge was opened in due form by command of the Grand Master in the Chair, Brother W. Preston as W.M., Bros. Gliddon and Pugh as S. and J. Wardens.

The Senior Warden rehearsed the Antient Charges on the Management of the Craft in working.

Masons employ themselves honestly on working days, live creditably on holydays; and the times appointed by the law of the land, as confirmed by custom are carefully observed; seven clauses which the ten clauses today in our Book of Constitutions elaborate with additions.

The Senior Warden then read: Laws for the Government of the Lodge. You are to salute one another in a cautious mannerNo private Committees are to be allowed.

These Laws are to be strictly observed [and so on.] Amen. So mote it be.

Clauses represented under "Behaviour" in our present version of the Antient Charges.

Toast. The King and the CraftFlourish with Horns. Brother Preston delivered his Oration, thus laying the foundation stone of his future Illustrations of Masonry. Toast. The Grand Master Flourish with Horns.

24 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES Ode, sung by three Brethren accompanied with the instruments Wake the lute and quiv'ring strings, Mystic truths Urania brings; This was succeeded by the Toast. The Deputy Grand Master and the Grand Wardens.

The six SECTIONS of the FIRST LECTURE were then rehearsed accompanied by vocal and instrumental music with the appropriate toasts.

SECTION I.

Song (duet) Hail Masonry Divine Glory of ages thine Long may'st thou reign, etc. Toast. All Masons, both ancient and young, Who govern their passions and bridle their tongue.

SECTION II.

Solemn Air Toast. The heart that conceals, and the tongue that never reveals any of the Secrets of Masonry.

SECTION III.

Anthem.

Grant us Kind Heav'n what we request In Memory let us be blest, etc.

Toast. All Masons who honour the Order by conforming to its rules.

SECTION IV.

Trio. Clarionets and Bassoon.

Toast. May we arrive at the summit of Masonry, and may the just never fail of their reward.

SECTION V.

Song.

Arise and blow thy trumpet Fame! Free Masonry aloud proclaim, To realms and worlds unknown, etc.

Toast. To the memory of the Holy Lodge of St. John.

SECTION VI.

Air (sprightly).

The Charge on the Behaviour of Masons was rehearsed by Brother Preston, leading up to the final toast "May the Cardinal Virtues, etc.," as recorded in my lecture.

During Brother Preston's Mastership of Antiquity in 1777 it was decided "that a Chapter of the Order should be held," and the Minutes record as follows: BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 25 Lodge opened in the Third Degree in an adjacent Room. Procession entered the Lodge Room, and the usual ceremonies being observed, the Three Rulers were seated. A piece of Music was then performed, and the 12 Assistants entered in procession, and after repairing to their stations the Chapter was opened in solemn form. Bro. Barker then rehearsed the Second Section. A piece of Music was then performed by the instruments. Brother Preston then rehearsed the Third Section. An Ode on Masonry was then sung by three voices. Bro. Hill rehearsed the 4th Section, after which a piece of solemn music was performed. Bro. Brearley rehearsed the 5th Section, and the funeral procession was formed during which a solemn dirge was played and this ceremony concluded with a Grand Chorus. Bro. Berkley rehearsed the 6th Section, after which an anthem was sung. Bro. Preston then rehearsed the 7th Section, after a song in honour of masonry, accompanied by the instruments, was sung. The Chapter was then closed with the usual solemnity, and the Rulers and twelve Assistants made the procession round the Lodge, and then withdrew to an adjacent Room where the Masters' Lodge was closed in due form.

APPENDIX B THE ORDER OF HARODIM.

A copy of the advertisement of the inauguration of the Order of Harodim preserved in the Grand Lodge Library is as follows: PLAN of the ANTIENT and VENERABLE ORDER of HARODIM To be INSTITUTED at the MITRE‑TAVERN, FLEET‑STREET Under the GENERAL DIRECTION of BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON PAST MASTER of the LODGE OF ANTIQUITY Acting by IMMEMORIAL CONSTITUTION.

This Order is to be under the management of a Chief Ruler and two Assistants, with a Council of twelve Companions to be elected annually, on the Festival of St. John the Evangelist.

26 THE PRESTONIAN LECTURES The Order to be composed of five Classes: First Class First Degree Second Class l Second Degree Third Class i to include Masons Third Degree Fourth Class in the Master of Arts Fifth Class Royal Arch Each Class to be under the direction of skilful Companions, selected from Brethren of established reputation in the Literary, Moral, and Philosophical World.

The first Meeting to be on Thursday, the 4th of.7anuary, 1787, at Six in the Evening when a preliminary Lecture will be delivered by Bro. Preston; after which the Meetings to be regularly continued every Thursday during the Months of January, February, March, April, October, November, and December, at Seven in the Evening, in a private Room engaged for that purpose, at the Mitre‑Tavern.

As Bro. PRESTON'S intention is to promote the general good purposes of Masonry throughout the World, on the Genuine, Original, and Constitutional Principles of that truly Antient and Honourable Institution without interfering with the Government of the Society either at home or abroad; and, if possible, to unite all Classes of his Brethren in one universal System, he flatters himself his Plan will be approved: And as nothing can tend more effectually to promote the intended design, than the proper application of such sums of Money as may be received on the admission of Brethren into the Separate Classes of the Order, Brother PRESTON engages that all such Sums, with the surplus of Accounts that may be settled by the Council, shall be deposited in the hands of an eminent Banker in the City of London, to be at the disposal of the General Meeting on the Festival of St. John the Evangelist, for the relief of poor and distressed Companions of the Order; and that the proceedings of the different Weekly Meetings, with the Names of the Companions as they are Enrolled, and the State of the Accounts, shall be regularly printed and distributed among the Members on the first Thursday of every Month, for which each Member shall pay one Shilling annually.

SUCH Brethren as are willing to encourage the Plan, and to be enrolled as Companions of this Venerable Order, are requested to favour Brother PRESTON with their Names, Professions, and Places of Residence, at his house, No. 3, DEAN‑STREET, Fetter‑Lane; or inclosed in a Letter, addressed to Mr. THOMAS CHAPMAN, Secretary to the Committee of the ORDER OF HARODIM, at the Mitre‑Tavern, Fleet‑Street, where the Committee Meet every Thursday, from Seven to Nine in the Evening; and if the said Brethren are approved by the Committee, they shall be enrolled, on paying Half‑a‑Crown, which will entitle them to attend all future Meetings in the First Class, free of Expence, and to rank as Companions of the Order for Life.

BROTHER WILLIAM PRESTON 27 When the reunion of the two bodies claiming the title of the Lodge of Antiquity had been happily accomplished, the Harodim Lodge was warranted by Grand Lodge on March 25th, 1790, designed by the petitioners to enable the Chapter to preserve a correspondence with Grand Lodge and to authorize it to practise the rites of Masonry under the auspices of this Lodge.

The Plan and Regulations of the Grand Order of Harodim printed in 1791 supply full particulars of its constitution and relationship with the Lodge.

We are told: The Order of Harodim is totally independent being established on its own basis; and as a Chapter, is no otherwise connected with the Society of Free Masons, than by having its members selected from that Fraternity. The Mysteries of the Order are peculiar to the Institution itself, while the Lectures of the Chapter include every branch of the Masonic System, and represent the Art of Masonry in a finished and complete form.