Reverend Brother John Marrant

&

Birchtown, Nova Scotia

By

Honorable Frederic L. Milliken

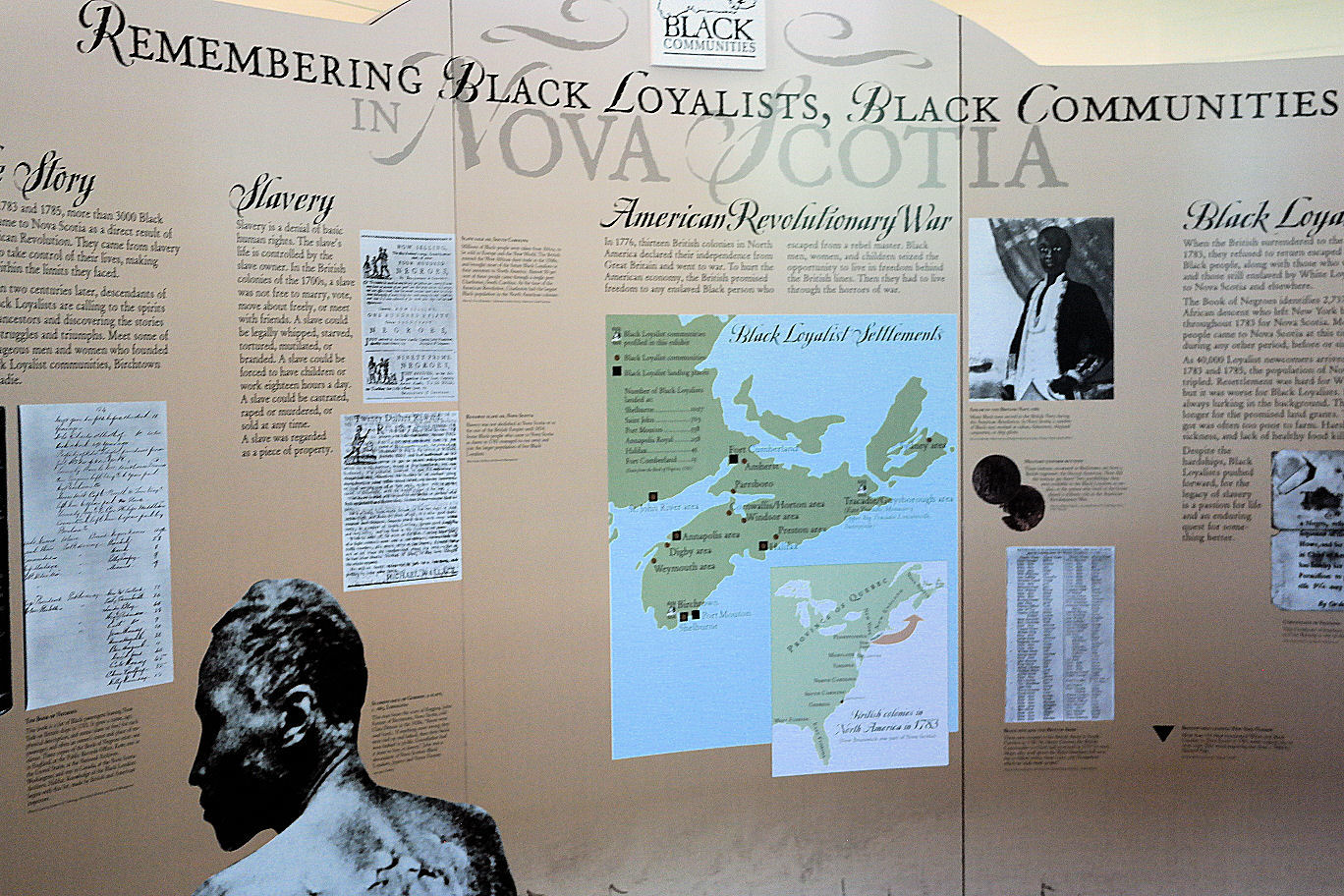

This year I made a family vacation trip back to Nova Scotia where I summered every year as a child. We visited many historical sites while there, among them was Shelburne, Nova Scotia. When I drove down the main street of Shelburne there were British flags everywhere and the word “Loyalist” was prominently used on signs, businesses and all things written.

So I was to relearn that a large contingent of White Americans, who wanted to remain loyal to the British Crown after the American Patriots defeated the British in the Revolutionary War, sailed to Nova Scotia in 1783 and settled in what is now the town of Shelburne. All this I guess I knew as a child but it was 51 years since I last set foot on Nova Scotia soil.

The town of Shelburne reports:

“In the spring of 1783, 5,000 settlers arrived on the shores of Shelburne Harbour from New York and the middle colonies of America. Assurance of living under the British flag, and promises of free land, tools, and provisions lured many to the British Colonies at that time. Four hundred families associated to form a town at Port Roseway, which Governor Parr renamed Shelburne later that year. This group became known as the Port Roseway Associates. In the fall of 1783, a second wave of settlers arrived in Shelburne. By 1784, the population of this new community is estimated to have been at least 10,000; the fourth largest in North America, much larger than either Halifax or Montreal.” (1)

What I didn’t know was that less than 10 miles down the road was a town settled by Black Loyalists in the same year. The town was named Birchtown in honor of British Brigadier General Samuel Birch who signed the majority of the Certificates of Freedom held by Black Loyalists most of whom had fought for the British during the Revolutionary War.

Certificate of Freedom signed by British Brigadier General Samuel Birch

Here is how that came about:

“When Lord Dunmore, Royal Governor of Virginia, lost control of that colony to the rebels in the summer of 1775, the economy of Virginia was based on slave labor. Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation that any slave or indentured person would be given their freedom if they took up arms with the British against the rebels. As a result, 2,000 slaves and indentured persons joined his forces. Later, other British supporters in the colonies issued similar proclamations.

Then the British Commander-in-chief at New York, Sir Henry Clinton, issued the Philipsburg proclamation when the British realized they were losing the war. It stated that any Negro to desert the rebel cause would receive full protection, freedom, and land. It is estimated that many thousands of people of African descent joined the British and became British supporters.” (2)

“When the end came, the top British commanders kept their word to the King's Black soldiers.

In November 1782, Britain and America signed a provisional treaty granting the former colonies their independence. As the British prepared for their final evacuation, the Americans demanded the return of American property, including runaway slaves, under the terms of the peace treaty. Sir Guy Carleton, the acting commander of British forces, refused to abandon black Loyalists to their fate as slaves. With thousands of apprehensive blacks seeking to document their service to the Crown, Brigadier General Samuel Birch, British commandant of the city of New York, created a list of claimants known as The Book of Negroes.” (3)

Some interesting behind the scenes bargaining led to this conclusion:

In April 1783 the first evacuation fleet left for Nova Scotia. A week later the British Commander, Sir Guy Carleton Carleton, sailed up the Hudson River to Orangetown for a conference with General Washington to discuss the evacuation. As the victorious commander, Washington opened the meeting by reiterating the resolution of Congress regarding “the delivery of all Negroes and other property.” In response, the defeated Carleton indicated that in his desire for a speedy evacuation he had already sent off some 6000 refugees, including “a number of Negroes.” Observers from both sides noted the general’s consternation as he remonstrated with Carleton that the action was against the express stipulation of the treaty. Calmly, Carleton offered an unapologetic explanation, saying that in his interpretation, the term property meant property owned by Americans at the time the treaty was signed, so did not include those who had responded to British proclamations years before. Never would the British government have agreed “to reduce themselves to the necessity of violating their faith to the Negroes,” he told Washington. Warming to his subject, he further insisted “delivering up Negroes to their former masters … would be a dishonourable violation of the public faith.” In the unlikely event that the British government put a different construction on the treaty, he promised compensation would be paid to the owners and to this end he had directed “a register be kept of all the Negroes who were sent off.” Protesting as he was bound to do, Washington understood the depth of feeling behind the words “dishonourable violation of the public faith.” By the time the meeting came to its inconclusive end, he had privately conceded defeat.

Carleton wrote in icy prose; “the Negroes in question, I have already said, I found free when I arrived at New York, I had therefore no right, as I thought, to prevent their going to any part of the world they thought proper.” Should Washington fail to comprehend his intransigence on this point, he added a thinly veiled warning: “I must confess the mere supposition that the King’s minister could deliberately stipulate in a treaty, an engagement to be guilty of the notorious breach of public faith towards people of any complexion, seems to denote a less friendly disposition than I would wish, and, I think, less friendly than we might expect.” (4)

The “Book of Negroes” was a record of every Black that got on a ship bound for Nova Scotia and left New York. What was recorded was ship, Captain, name, where bound, person’s name, age, description and free or non-free (claimant). Some 114 ships were gathered for the deportation and 3000 Blacks headed for various parts of Nova Scotia with another 2000 electing to go elsewhere (Other Canadian ports, England, Jamaica, The Bahamas, Germany and Belgium). Here is how it is reported by The Nova Scotia Museum:

Replica of the Book of Negroes at the Black Loyalist Heritage Museum, Birchtown, Nova Scotia

“The British-American Commission identified the Black people in New York who had joined the British before the surrender, and issued "certificates of freedom" signed by General Birch or General Musgrave. Those who chose to emigrate were evacuated by ship. To make sure no one attempted to leave who did not have a certificate of freedom, the name of any Black person on board a vessel, whether slave, indentured servant, or free, was recorded, along with the details of enslavement, escape, and military service, in a document called the Book of Negroes (2)

Unfortunately the Nova Scotia experience proved to be a tough go for emigrating Blacks. The winters were harsh, much of the land unarable and along with broken promises life became unbearable. While almost all Blacks in Birchtown received town lots only about one third of them received farmland. Of 649 Black men who applied for Beaver Dam land grants only 187 received them. The Whites had settled first and grabbed the best of what good farm land there was. Consequently many Blacks became indentured servants or share croppers. (5)

Into these struggles for existence came Reverend John Marrant in 1785 to minister to the Black Loyalists, poor Whites, and the Micmac Indians. Marrant a free Black born in New York moved to the South at an early age upon the death of his father. His family moved from Florida to Georgia to Charleston, South Carolina. Instead of learning a trade, Marrant became an accomplished musician and it is this talent that took him to a church where George Whitefield was preaching. Converted on the spot to Christianity and still a teenager he headed for the forests when he had difficulty getting along with his family. There he lived with and preached to Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Catawars, and Howsaws Indians for a number of years before returning home. At home he started preaching to the slaves on the Jenkins Plantation. When the Revolutionary War broke out in 1775, Marrant served in the British Navy as a cannoneer. After the war he retired to London working for a cotton merchant. He also preached at the Spa-Fields Chapel where he attracted the attention of the Chapel’s benefactor, the Countess of Huntingdon. She arranged Marrant’s ordination and subsequent service to Birchtown, Nova Scotia.

Marrant along with George Whitefield were members of the Huntingdon Connection that held to a strict doctrine of predestination as distinguished from Charles and John Wesley who held to a salvation by faith alone.

I visited the Black Loyalist Heritage Museum in Nova Scotia and took the 11/2 hour guided tour. The tour consisted of three locations, the Museum itself, St. Paul Anglican Church and the Black burying grounds. All were grouped together in one big parcel of land. I viewed the Book of Negroes at the Museum, watched a film at the church and stood where unmarked graves were below my feet.

Black Loyalist Heritage Museum, Birchtown, Nova Scotia

VIEW VIDEO: http://youtu.be/Af4OGbYBS7I

Because of hard times and a withdrawal of support from the Huntingdon Connection, Marrant left Birchtown, Nova Scotia in 1788 and headed for Boston.

“By 1789, all of North America was in the grip of a serious famine. The winters had been long and cold for the past several years, and the settlers' dreams of establishing farms were dashed by poor land and a desperate scarcity of farming's necessities. Land grants had taken far too long to arrive, and when they did, most had wasted their savings simply keeping themselves alive.”

“Famine struck everybody, white and black alike. Ships from Montreal arrived in Halifax and were desperately seeking rations to relieve them.” “Since Halifax was no better off, they were sent away. Nova Scotia's population was tripled in a few short years by Loyalist refugees. When the British stopped supporting them, the entire province plunged into poverty. Nova Scotia had truly earned it's nickname of Nova Scarcity.”

“However, most of the whites had a better option available to them. They could return to the United States, where tensions had cooled considerably and most of them had family. Most of them did exactly that. Shelburne was hardly the New York of the North, which was what they had hoped for. Even wealthy merchants had largely been reduced to poverty. Farming was nearly an impossibility. Merchants had nobody worth trading with due to restrictions on trade with the US and various mercantile laws. Even the whaling industry had collapsed. Only fishing offered a opportunity to earn a decent living.”

“Former slaves had no such options. For them the choice was a brutal one: misery or death. The people who had employed them, albeit under exploitative conditions, departed for the United States. A bad situation got much worse. Without farmland or anybody to employ them, most of the free blacks became dependent on charity.” (6)

After too many years of misery, in 1792 one third of the Black population of Birchtown along with Blacks from other Nova Scotia settlements boarded ships for Sierra Leone where they were promised supplies and land. They founded the city of Freetown and to this day relatives from the same family are divided. Some live in Nova Scotia still and others in Freetown, Africa.

VIEW VIDEO: http://youtu.be/MIKTHKvHQTs

Meanwhile Marrant landed in Boston and in March 1789 was introduced to Prince Hall. He ended staying with Hall a short time at Hall’s home. No one knows where Marrant was made a Freemason, whether he was initiated in London or by Prince Hall. But what we do know that Prince Hall became smitten with Marrant and quickly appointed him as chaplain of African Lodge #459.

Not only that but a scant few months later Prince Hall charged Marrant to give the address to African Lodge #459 on St. John the Baptist’s Day, June 24, 1789. And Joanna Brooks tells us that Hall even recruited two White Masons to print and distribute Marrant’s sermon address. (7) This was the first printed formal address before the first African Lodge and among the first printed works by an African American in Western Civilization in the latter part of the Eighteenth Century. (8)

“Marrant preached that day a message of the equality of all men and the African roots of Christianity and Freemasonry. However, Marrant was also advancing some new theological ideas dangerous to established authority in his Connection as well as generally. Marrant's ideas were egalitarian in nature: They promoted the dismissal of scholastic pietism and established the importance of the individual's reading of scripture. Marrant preached that the New Testament was the sole authority and arbiter between the individual and salvation, and that Christians should incorporate their own experiences in readings of the Bible. He also advanced extemporaneous or "inspired" preaching and prayer as indicators of genuine Christian development and of godly connection. Marrant is clearly disdainful of "learned," scholastic Christianity, and he suggests individuals--independent of traditional hierarchical authorities--are capable of inspired readings of the Scriptures, and this practice is the center of Christian theology and worship. Most Congregational Christians, particularly the ministers of established churches in a cosmopolitan community like Boston, would have shunned such ideas because they undermined the authority that they had spent so much time and effort in school attaining. This direct attack rejects established doctrines. It implies that common folk could glean the meaning of Scripture, independent of established church authorities. (9)

Reverend John Marrant was on the best seller list of books of his day. His three publications were enormous hits in England as well as the United States.

His published works were:

- A Narrative of the Lord’s Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant, A Black, 1785

- A Sermon Preached on the 24th Day of June 1789…at the Request of the Right Worshipful the Grand Master Prince Hall, and the Rest of the Brethren of the African Lodge of the Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons in Boston, 1789

- A Journal of the Rev. John Marrant, from August the 18th, 1785, to the 16th of March, 1790

The first was reprinted 17 times.

It is said that Marrant had a profound influence on Prince Hall and Hall’s theology. This is really only half the story. But the second half has already been written by our own Honorable Gregory S. Kearse in an article from the Phylaxis Magazine, Third Quarter 2014 titled “The Influence Of The Reverend John Marrant’s Sermon On Prince Hall’s Charges Of 1792 & 1797.” It is here you need to go to complete the story.

The Reverend John Marrant was a lot like Martin Luther King. He had an enormous influence in a short period of time and died too soon. Marrant was not assassinated but he did go back to England after only two short years in Boston in 1790. The following year, 1791, he died at the age of 35.

He left a legacy of profound influence on the Black community and throughout Christendom.

“Although his knowledge and use of orthodox Calvinism was the means by which he was able to secure initial funding for his ministry, it was a progressive Calvinism he taught to his congregations. The discourse of his ministry is rooted in the discourse of freedom and egalitarianism that the Black revolutionaries and Black Loyalists shared with one another. As a veteran Loyalist who fought in the Revolutionary War, who then returned to North American to preach to Loyalist immigrants and become chaplain of African Lodge 459 in Boston, Marrant reveals a faith that Christian community, particularly among Black people, far outweighed the nationalist and sectarian interests of his day. His Narrative illuminates the roots of Black theology that engaged in progressive social action in both principle and practice. With these progressive religious roots, the principles he promoted would flourish in African American culture and yield fruit in some part of virtually every major religious, and often secular, Black institution developed since.” (9)

Let us remember these words he delivered to African Lodge #459.

“Let all my brethren Masons consider what they are called to – May God grant you an humble heart to fear God and love his commandment; then and only then you will in sincerity love your brethren: And you will be enabled…to be kindly affectioned one to another, with brotherly love in honour preferring one another…This we profess to believe as Christians and as Masons.” (10)

VIEW VIDEO: http://youtu.be/SAB5nKP3mbM

(1) Town of Shelburne, Nova Scotia - http://www.town.shelburne.ns.ca/history.html.

(2) Remembering Black Loyalists - Who were Black Loyalists? – Nova Scotia Museum - http://novascotia.ca/museum/blackloyalists/who.htm

(3) The Black Commentator - http://www.blackcommentator.com/washingtons_slaves.html

(4) Black Loyalist Heritage society, Evacuation of New York

http://www.blackloyalist.info/event/display/9

(5) Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People: Suffering: Still Landless http://blackloyalist.com/cdc/story/suffering/landless.htm

(6) Black Loyalists: Our History, Our People: Suffering: Famine In Nova Scarcity - http://blackloyalist.com/cdc/story/suffering/scarcity.htm

(7) Prince Hall, Freemasonry, and Genealogy , Joanna Brooks, The Free Library - http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Prince+Hall%2c+Freemasonry%2c+and+Genealogy.-a064397587

(8) John Marrant and the Meaning of Early Black Freemasonry, Peter P. Hinks http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/4491600?uid=3739920&uid=2&uid=4&uid=3739256&sid=21104574131191

(9) John Marrant and the narrative construction of an early black Methodist evangelical, Cedrick May, The Free Library - http://www.thefreelibrary.com/John+Marrant+and+the+narrative+construction+of+an+early+black...-a0132866627

(10) A Sermon Preached on the 24th Day of June 1789…at the Request of the Right Worshipful the Grand Master Prince Hall, and the Rest of the Brethren of the African Lodge of the Honorable Society of Free and Accepted Masons in Boston, 1789 – John Marrant.