Conclusion

PHILIP, King of Macedon, ambitious to obtain the teacher who would be most capable of imparting the higher branches of learning to his fourteen-year-old son, Alexander, and wishing the prince to have for his mentor the most famous and learned of the great philosophers, decided to communicate with Aristotle. He dispatched the following letter to the Greek sage: "PHILIP TO ARISTOTLE, HEALTH: Know that I have a son. I render the gods many thanks; not so much for his birth, as that he was born in your time, for I hope that being educated and instructed by you, he will become worthy of us both and the kingdom which he shall inherit." Accepting Philip's invitation, Aristotle journeyed to Macedon in the fourth year of the 108th Olympiad, and remained for eight years as the tutor of Alexander. The young prince's affection for his instructor became as great as that which he felt for his father. He said that his father had given him being, but that Aristotle had given him well-being.

The basic principles of the Ancient Wisdom were imparted to Alexander the Great by Aristotle, and at the philosopher's feet the Macedonian youth came to realize the transcendency of Greek learning as it was personified in Plato's immortal disciple. Elevated by his illumined teacher to the threshold of the philosophic sphere, he beheld the world of the sages--the world that fate and the limitations of his own soul decreed he should not conquer.

Aristotle in his leisure hours edited and annotated the Iliad of Horner and presented the finished volume to Alexander. This book the young conqueror so highly prized that he carried it with him on all his campaigns. At the time of his triumph over Darius, discovering among the spoils a magnificent, gem-studded casket of unguents, he dumped its contents upon the ground, declaring that at last he had found a case worthy of Aristotle's edition of the Iliad!

While on his Asiatic campaign, Alexander learned that Aristotle had published one of his most prized discourses, an occurrence which deeply grieved the young king. So to Aristotle, Conqueror of the Unknown, Alexander, Conqueror of the Known, sent this reproachful and pathetic and admission of the insufficiency of worldly pomp and power: "ALEXANDER TO ARISTOTLE, HEALTH: You were wrong in publishing those branches of science hitherto not to be acquired except from oral instruction. In what shall I excel others if the more profound knowledge I gained from you be communicated to all? For my part I had rather surpass the majority of mankind in the sublimer branches of learning, than in extent of power and dominion. Farewell." The receipt of this amazing letter caused no ripple in the placid life of Aristotle, who replied that although the discourse had been communicated to the multitudes, none who had not heard him deliver the lecture (who lacked spiritual comprehension) could understand its true import.

A few short years and Alexander the Great went the way of all flesh, and with his body crumbled the structure of empire erected upon his personality. One year later Aristotle also passed into that greater world concerning whose mysteries he had so often discoursed with his disciples in the Lyceum. But, as Aristotle excelled Alexander in life, so he excelled him in death; for though his body moldered in an obscure tomb, the great philosopher continued to live in his intellectual achievements. Age after age paid him grateful tribute, generation after generation pondered over his theorems until by the sheer transcendency of his rational faculties Aristotle--"the master of those who know," as Dante has called him--became the actual conqueror of the very world which Alexander had sought to subdue with the sword.

Thus it is demonstrated that to capture a man it is not sufficient to enslave his body--it is necessary to enlist his reason; that to free a man it is not enough to strike the shackles from his limbs--his mind must be liberated from bondage to his own ignorance. Physical conquest must ever fail, for, generating hatred and dissension, it spurs the mind to the avenging of an outraged body; but all men are bound whether willingly or unwillingly to obey that intellect in which they recognize qualities and virtues superior to their own.

That the philosophic culture of ancient Greece, Egypt, and India excelled that of the modern, world must be admitted by all, even by the most confirmed of modernists. The golden era of Greek ęsthetics, intellectualism, and ethics has never since been equaled. The true philosopher belongs to the most noble order of men: the nation or race which is blessed by possession of illumined thinkers is fortunate indeed, and its name shall be remembered for their sake. In the famous Pythagorean school at Crotona, philosophy was regarded as indispensable to the life of man. He who did not comprehend the dignity of the reasoning power could not properly be said to live. Therefore, when through innate perverseness a member either voluntarily withdrew or was forcibly ejected from the philosophic fraternity, a headstone was set up for him in the community graveyard; for he who had forsaken intellectual and ethical pursuits to reenter the material sphere with its illusions of sense and false ambition was regarded as one dead to the sphere of Reality. The life represented by the thraldom of the senses the Pythagoreans conceived to be spiritual death, while they regarded death to the sense-world as spiritual life.

Philosophy bestows life in that it reveals the dignity and purpose of living. Materiality bestows death in that it benumbs or clouds those faculties of the human soul which should be responsive to the enlivening impulses of creative thought and ennobling virtue. How inferior to these standards of remote days are the laws by which men live in the twentieth century! Today man, a sublime creature with infinite capacity for self-improvement, in an effort to be true to false standards, turns from his birthright of understanding--without realizing the consequences--and plunges into the maelstrom of material illusion. The precious span of his earthly years he devotes to the pathetically futile effort to establish himself as an enduring power in a realm of unenduring things. Gradually the memory of his life as a spiritual being vanishes from his objective mind and he focuses all his partly awakened faculties upon

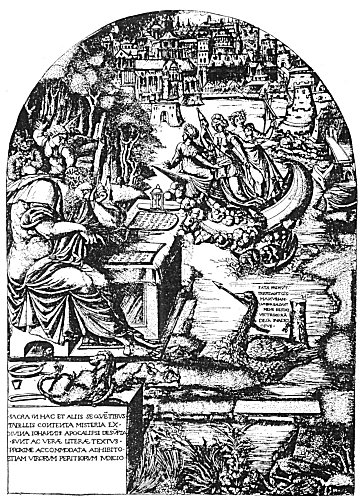

JOHN AND THE VISION OF THE APOCALYPSE.From an engraving by Jean Duvet.

Jean Duvet of Langres (who was born in 1485 and presumably died sometime after 1561, the year in which his illustrations to the Apocalypse were printed in book form) was the oldest and greatest of French Renaissance engravers. Little is known concerning Duvet beyond the fact that he was the goldsmith to the King of France. His engravings for the Book of Revelation, executed after he had passed his seventieth year, were his masterpiece. (For further information regarding this obscure master, consult article by William M. Ivins, Jr., in The Arts, May, 1926.) The face of John is an actual portrait of Duvet. This plate, like many others cut by Duvet, is rich in philosophical symbolism.

the seething beehive of industry which he has come to consider the sole actuality. From the lofty heights of his Selfhood he slowly sinks into the gloomy depths of ephemerality. He falls to the level of the beast, and in brutish fashion mumbles the problems arising from his all too insufficient knowledge of the Divine Plan. Here in the lurid turmoil of a great industrial, political, commercial inferno, men writhe in self-inflicted agony and, reaching out into the swirling mists, strive to clutch and hold the grotesque phantoms of success and power.

Ignorant of the cause of life, ignorant of the purpose of life, ignorant of what lies beyond the mystery of death, yet possessing within himself the answer to it all, man is willing to sacrifice the beautiful, the true, and the good within and without upon the blood-stained altar of worldly ambition. The world of philosophy--that beautiful garden of thought wherein the sages dwell in the bond of fraternity--fades from view. In its place rises an empire of stone, steel, smoke, and hate-a world in which millions of creatures potentially human scurry to and fro in the desperate effort to exist and at the same time maintain the vast institution which they have erected and which, like some mighty, juggernaut, is rumbling inevitably towards an unknown end. In this physical empire, which man erects in the vain belief that he can outshine the kingdom of the celestials, everything is changed to stone, Fascinated by the glitter of gain, man gazes at the Medusa-like face of greed and stands petrified.

In this commercial age science is concerned solely with the classification of physical knowledge and investigation of the temporal and illusionary parts of Nature. Its so-called practical discoveries bind man but more tightly with the bonds of physical limitation, Religion, too, has become materialistic: the beauty and dignity of faith is measured by huge piles of masonry, by tracts of real estate, or by the balance sheet. Philosophy which connects heaven and earth like a mighty ladder, up the rungs of which the illumined of all ages have climbed into the living presence of Reality--even philosophy has become a prosaic and heterogeneous mass of conflicting notions. Its beauty, its dignity, its transcendency are no more. Like other branches of human thought, it has been made materialistic--"practical"--and its activities so directionalized that they may also contribute their part to the erection of this modern world of stone and steel.

In the ranks of the so-called learned there is rising up a new order of thinkers, which may best be termed the School of the Worldly Wise Men. After arriving at the astounding conclusion that they are the intellectual salt of the earth, these gentlemen of letters have appointed themselves the final judges of all knowledge, both human and divine. This group affirms that all mystics must have been epileptic and most of the saints neurotic! It declares God to be a fabrication of primitive superstition; the universe to be intended for no particular purpose; immortality to be a figment of the imagination; and an outstanding individuality to be but a fortuitous combination of cells! Pythagoras is asserted to have suffered from a "bean complex"; Socrates was a notorious inebriate; St. Paul was subject to fits; Paracelsus was an infamous quack, the Comte di Cagliostro a mountebank, and the Comte de St.-Germain the outstanding crook of history!

What do the lofty concepts of the world's illumined saviors and sages have in common with these stunted, distorted products of the "realism" of this century? All over the world men and women ground down by the soulless cultural systems of today are crying out for the return of the banished age of beauty and enlightenment--for something practical in the highest sense of the word. A few are beginning to realize that so-called civilization in its present form is at the vanishing point; that coldness, heartlessness, commercialism, and material efficiency are impractical, and only that which offers opportunity for the expression of love and ideality is truly worth while. All the world is seeking happiness, but knows not in what direction to search. Men must learn that happiness crowns the soul's quest for understanding. Only through the realization of infinite goodness and infinite accomplishment can the peace of the inner Self be assured. In spite of man's geocentricism, there is something in the human mind that is reaching out to philosophy--not to this or that philosophic code, but simply to philosophy in the broadest and fullest sense.

The great philosophic institutions of the past must rise again, for these alone can tend the veil which divides the world of causes from that of effects. Only the Mysteries--those sacred Colleges of Wisdom--can reveal to struggling humanity that greater and more glorious universe which is the true home of the spiritual being called man. Modern philosophy has failed in that it has come to regard thinking as simply an intellectual process. Materialistic thought is as hopeless a code of life as commercialism itself. The power to think true is the savior of humanity. The mythological and historical Redeemers of every age were all personifications of that power. He who has a little more rationality than his neighbor is a little better than his neighbor. He who functions on a higher plane of rationality than the rest of the world is termed the greatest thinker. He who functions on a lower plane is regarded as a barbarian. Thus comparative rational development is the true gauge of the individual's evolutionary status.

Briefly stated, the true purpose of ancient philosophy was to discover a method whereby development of the rational nature could be accelerated instead of awaiting the slower processes of Nature, This supreme source of power, this attainment of knowledge, this unfolding of the god within, is concealed under the epigrammatic statement of the philosophic life. This was the key to the Great Work, the mystery of the Philosopher's Stone, for it meant that alchemical transmutation had been accomplished. Thus ancient philosophy was primarily the living of a life; secondarily, an intellectual method. He alone can become a philosopher in the highest sense who lives the philosophic life. What man lives he comes to know. Consequently, a great philosopher is one whose threefold life--physical, mental, and spiritual--is wholly devoted to and completely permeated by his rationality.

Man's physical, emotional, and mental natures provide environments of reciprocal benefit or detriment to each other. Since the physical nature is the immediate environment of the mental, only that mind is capable of rational thinking which is enthroned in a harmonious and highly refined material constitution. Hence right action, right feeling, and right thinking are prerequisites of right knowing, and the attainment of philosophic power is possible only to such as have harmonized their thinking with their living. The wise have therefore declared that none can attain to the highest in the science of knowing until first he has attained to the highest in the science of living. Philosophic power is the natural outgrowth of the philosophic life. Just as an intense physical existence emphasizes the importance of physical things, or just as the monastic metaphysical asceticism establishes the desirability of the ecstatic state, so complete philosophic absorption ushers the consciousness of the thinker into the most elevated and noble of all spheres--the pure philosophic, or rational, world.

In a civilization primarily concerned with the accomplishment of the extremes of temporal activity, the philosopher represents an equilibrating intellect capable of estimating and guiding the cultural growth. The establishment of the philosophic rhythm in the nature of an individual ordinarily requires from fifteen to twenty years. During that entire period the disciples of old were constantly subjected to the most severe discipline. Every activity of life was gradually disengaged from other interests and focalized upon the reasoning part. In the ancient world there was another and most vital factor which entered into the production of rational intellects and which is entirely beyond the comprehension of modern thinkers: namely, initiation into the philosophic Mysteries. A man who had demonstrated his peculiar mental and spiritual fitness was accepted into the body of the learned and to him was revealed that priceless heritage of arcane lore preserved from generation to generation. This heritage of philosophic truth is the matchless treasure of all ages, and each disciple admitted into these brotherhoods of the wise made, in turn, his individual contribution to this store of classified knowledge.

The one hope of the world is philosophy, for all the sorrows of modern life result from the lack of a proper philosophic code. Those who sense even in part the dignity of life cannot but realize the shallowness apparent in the activities of this age. Well has it been said that no individual can succeed until he has developed his philosophy of life. Neither can a race or nation attain true greatness until it has formulated an adequate philosophy and has dedicated its existence to a policy consistent with that philosophy. During the World War, when so-called civilization hurled one half of itself against the other in a frenzy of hate, men ruthlessly destroyed something more precious even than human life: they obliterated those records of human thought by which life can be intelligently directionalized. Truly did Mohammed declare the ink of philosophers to be more precious than the blood of martyrs. Priceless documents, invaluable records of achievement, knowledge founded on ages of patient observation and experimentation by the elect of the earth--all were destroyed with scarcely a qualm of regret. What was knowledge, what was truth, beauty, love, idealism, philosophy, or religion when compared to man's desire to control an infinitesimal spot in the fields of Cosmos for an inestimably minute fragment of time? Merely to satisfy some whim or urge of ambition man would uproot the universe, though well he knows that in a few short years he must depart, leaving all that he has seized to posterity as an old cause for fresh contention.

War--the irrefutable evidence of irrationality--still smolders in the hearts of men; it cannot die until human selfishness is overcome. Armed with multifarious inventions and destructive agencies, civilization will continue its fratricidal strife through future ages, But upon the mind of man there is dawning a great fear--the fear that

THE ENTRANCE TO THE HOUSE OF THE MYSTERIES.From Khunrath's Amphitheatrum Sapientię, etc.

This symbolic figure, representing the way to everlasting life, is described by Khunrath in substance as follows: "This is the Portal of the amphitheatre of the only true and eternal Wisdom--a narrow one, indeed, but sufficiently august, and consecrated to Jehovah. To this portal ascent is made by a mystic, indisputably prologetic, flight of steps, set before it as shown in the picture. It consists of seven theosophic, or, rather, philosophic steps of the Doctrine of the Faithful Sons. After ascending the steps, the path is along the way of God the Father, either directly by inspiration or by various mediate means. According to the seven oracular laws shining at the portal, those who are inspired divinely have the power to enter and with the eyes of the body and of the mind, of seeing, contemplating and investigating in a Christiano-Kabalistic, divino-magical, physico-chemical manner, the nature of the Wisdom: Goodness, and Power of the Creator; to the end that they die not sophistically but live theosophically, and that the orthodox philosophers so created may with sincere philosophy expound the works of the Lord, and worthily praise God who has thus blessed these friend, of God." The above figure and description constitute one of the most remarkable expositions ever made of the appearance of the Wise Man's House and the way by which it must be entered.

____________________________

eventually civilization will destroy itself in one great cataclysmic struggle. Then must be reenacted the eternal drama of reconstruction. Out of the ruins of the civilization which died when its idealism died, some primitive people yet in the womb of destiny must build a new world. Foreseeing the needs of that day, the philosophers of the ages have desired that into the structure of this new world shall be incorporated the truest and finest of all that has gone before. It is a divine law that the sum of previous accomplishment shall be the foundation of each new order of things. The great philosophic treasures of humanity must be preserved. That which is superficial may he allowed to perish; that which is fundamental and essential must remain, regardless of cost.

Two fundamental forms of ignorance were recognized by the Platonists: simple ignorance and complex ignorance. Simple ignorance is merely lack of knowledge and is common to all creatures existing posterior to the First Cause, which alone has perfection of knowledge. Simple ignorance is an ever-active agent, urging the soul onward to the acquisition of knowledge. From this virginal state of unawareness grows the desire to become aware with its resultant improvement in the mental condition. The human intellect is ever surrounded by forms of existence beyond the estimation of its partly developed faculties. In this realm of objects not understood is a never-failing source of mental stimuli. Thus wisdom eventually results from the effort to cope rationally with the problem of the unknown.

In the last analysis, the Ultimate Cause alone can be denominated wise; in simpler words, only God is good. Socrates declared knowledge, virtue, and utility to be one with the innate nature of good. Knowledge is a condition of knowing; virtue a condition of being; utility a condition of doing. Considering wisdom as synonymous with mental completeness, it is evident that such a state can exist only in the Whole, for that which is less than the Whole cannot possess the fullness of the All. No part of creation is complete; hence each part is imperfect to the extent that it falls short of entirety. Where incompleteness is, it also follows that ignorance must be coexistent; for every part, while capable of knowing its own Self, cannot become aware of the Self in the other parts. Philosophically considered, growth from the standpoint of human evolution is a process proceeding from heterogeneity to homogeneity. In time, therefore, the isolated consciousness of the individual fragments is reunited to become the complete consciousness of the Whole. Then, and then only, is the condition of all-knowing an absolute reality.

Thus all creatures are relatively ignorant yet relatively wise; comparatively nothing yet comparatively all. The microscope reveals to man his significance; the telescope, his insignificance. Through the eternities of existence man is gradually increasing in both wisdom and understanding; his ever-expanding consciousness is including more of the external within the area of itself. Even in man's present state of imperfection it is dawning upon his realization that he can never be truly happy until he is perfect, and that of all the faculties contributing to his self-perfection none is equal in importance to the rational intellect. Through the labyrinth of diversity only the illumined mind can, and must, lead the soul into the perfect light of unity.

In addition to the simple ignorance which is the most potent factor in mental growth there exists another, which is of a far more dangerous and subtle type. This second form, called twofold or complex ignorance, may be briefly defined as ignorance of ignorance. Worshiping the sun, moon, and stars, and offering sacrifices to the winds, the primitive savage sought with crude fetishes to propitiate his unknown gods. He dwelt in a world filled with wonders which he did not understand. Now great cities stand where once roamed the Crookboned men. Humanity no longer regards itself as primitive or aboriginal. The spirit of wonder and awe has been succeeded by one of sophistication. Today man worships his own accomplishments, and either relegates the immensities of time and space to the background of his consciousness or disregards them entirely.

The twentieth century makes a fetish of civilization and is overwhelmed by its own fabrications; its gods are of its own fashioning. Humanity has forgotten how infinitesimal, how impermanent and how ignorant it actually is. Ptolemy has been ridiculed for conceiving the earth to be the center of the universe, yet modern civilization is seemingly founded upon the hypothesis that the planet earth is the most permanent and important of all the heavenly spheres,

and that the gods from their starry thrones are fascinated by the monumental and epochal events taking place upon this spherical ant-hill in Chaos.

From age to age men ceaselessly toil to build cities that they may rule over them with pomp and power--as though a fillet of gold or ten million vassals could elevate man above the dignity of his own thoughts and make the glitter of his scepter visible to the distant stars. As this tiny planet rolls along its orbit in space, it carries with it some two billion human beings who live and die oblivious to that immeasurable existence lying beyond the lump on which they dwell. Measured by the infinities of time and space, what are the captains of industry or the lords of finance? If one of these plutocrats should rise until he ruled the earth itself, what would he be but a petty despot seated on a grain of Cosmic dust?

Philosophy reveals to man his kinship with the All. It shows him that he is a brother to the suns which dot the firmament; it lifts him from a taxpayer on a whirling atom to a citizen of Cosmos. It teaches him that while physically bound to earth (of which his blood and bones are part), there is nevertheless within him a spiritual power, a diviner Self, through which he is one with the symphony of the Whole. Ignorance of ignorance, then, is that self-satisfied state of unawareness in which man, knowing nothing outside the limited area of his physical senses, bumptiously declares there is nothing more to know! He who knows no life save the physical is merely ignorant; but he who declares physical life to be all-important and elevates it to the position of supreme reality--such a one is ignorant of his own ignorance.

If the Infinite had not desired man to become wise, He would not have bestowed upon him the faculty of knowing. If He had not intended man to become virtuous, He would not have sown within the human heart the seeds of virtue. If He had predestined man to be limited to his narrow physical life, He would not have equipped him with perceptions and sensibilities capable of grasping, in part at least, the immensity of the outer universe. The criers of philosophy call all men to a comradeship of the spirit: to a fraternity of thought: to a convocation of Selves. Philosophy invites man out of the vainness of selfishness; out of the sorrow of ignorance and the despair of worldliness; out of the travesty of ambition and the cruel clutches of greed; out of the red hell of hate and the cold tomb of dead idealism.

Philosophy would lead all men into the broad, calm vistas of truth, for the world of philosophy is a land of peace where those finer qualities pent up within each human soul are given opportunity for expression. Here men are taught the wonders of the blades of grass; each stick and stone is endowed with speech and tells the secret of its being. All life, bathed in the radiance of understanding, becomes a wonderful and beautiful reality. From the four corners of creation swells a mighty anthem of rejoicing, for here in the light of philosophy is revealed the purpose of existence; the wisdom and goodness permeating the Whole become evident to even man's imperfect intellect. Here the yearning heart of humanity finds that companionship which draws forth from the innermost recesses of the soul that great store of good which lies there like precious metal in some deep hidden vein.

Following the path pointed out by the wise, the seeker after truth ultimately attains to the summit of wisdom's mount, and gazing down, beholds the panorama of life spread out before him. The cities of the plains are but tiny specks and the horizon on every hand is obscured by the gray haze of the Unknown. Then the soul realizes that wisdom lies in breadth of vision; that it increases in comparison to the vista. Then as man's thoughts lift him heavenward, streets are lost in cities, cities in nations, nations in continents, continents in the earth, the earth in space, and space in an infinite eternity, until at last but two things remain: the Self and the goodness of God.

While man's physical body resides with him and mingles with the heedless throng, it is difficult to conceive of man as actually inhabiting a world of his own-a world which he has discovered by lifting himself into communion with the profundities of his own internal nature. Man may live two lives. One is a struggle from the womb to the tomb. Its span is measured by man's own creation--time. Well may it be called the unheeding life. The other life is from realization to infinity. It begins with understanding, its duration is forever, and upon the plane of eternity it is consummated. This is called the philosophic life. Philosophers are nor born nor do they die; for once having achieved the realization of immortality, they are immortal. Having once communed with Self, they realize that within there is an immortal foundation that will not pass away. Upon this living, vibrant base--Self--they erect a civilization which will endure after the sun, the moon, and the stars have ceased to be. The fool lives but for today; the philosopher lives forever.

When once the rational consciousness of man rolls away the stone and comes forth from its sepulcher, it dies no more; for to this second or philosophic birth there is no dissolution. By this should not be inferred physical immortality, but rather that the philosopher has learned that his physical body is no more his true Self than the physical earth is his true world. In the realization that he and his body are dissimilar--that though the form must perish the life will not fail--he achieves conscious immortality. This was the immortality to which Socrates referred when he said: "Anytus and Melitus may indeed put me to death, but they cannot injure me." To the wise, physical existence is but the outer room of the hall of life. Swinging open the doors of this antechamber, the illumined pass into the greater and more perfect existence. The ignorant dwell in a world bounded by time and space. To those, however, who grasp the import and dignity of Being, these are but phantom shapes, illusions of the senses-arbitrary limits imposed by man's ignorance upon the duration of Deity. The philosopher lives and thrills with the realization of this duration, for to him this infinite period has been designed by the All-Wise Cause as the time of all accomplishment.

Man is not the insignificant creature that he appears to be; his physical body is not the true measure of his real self. The invisible nature of man is as vast as his comprehension and as measureless as his thoughts. The fingers of his mind reach out and grasp the stars; his spirit mingles with the throbbing life of Cosmos itself. He who has attained to the state of understanding thereby has so increased his capacity to know that he gradually incorporates within himself the various elements of the universe. The unknown is merely that which is yet to be included within the consciousness of the seeker. Philosophy assists man to develop the sense of appreciation; for as it reveals the glory and the sufficiency of knowledge, it also unfolds those latent powers and faculties whereby man is enabled to master the secrets of the seven spheres.

From the world of physical pursuits the initiates of old called their disciples into the life of the mind and the spirit. Throughout the ages, the Mysteries have stood at the threshold of Reality--that hypothetical spot between noumenon and phenomenon, the Substance and the shadow. The gates of the Mysteries stand ever ajar and those who will may pass through into the spacious domicile of spirit. The world of philosophy lies neither to the right nor to the left, neither above nor below. Like a subtle essence permeating all space and all substance, it is everywhere; it penetrates the innermost and the outermost parts of all being. In every man and woman these two spheres are connected by a gate which leads from the not-self and its concerns to the Self and its realizations. In the mystic this gate is the heart, and through spiritualization of his emotions he contacts that more elevated plane which, once felt and known, becomes the sum of the worth-while. In the philosopher, reason is the gate between the outer and the inner worlds, the illumined mind bridging the chasm between the corporeal and the incorporeal. Thus godhood is born within the one who sees, and from the concerns of men he rises to the concerns of gods.

In this era of "practical" things men ridicule even the existence of God. They scoff at goodness while they ponder with befuddled minds the phantasmagoria of materiality. They have forgotten the path which leads beyond the stars. The great mystical institutions of antiquity which invited man to enter into his divine inheritance have crumbled, and institutions of human scheming now stand where once the ancient houses of learning rose a mystery of fluted columns and polished marble. The white-robed sages who gave to the world its ideals of culture and beauty have gathered their robes about them and departed from the sight of men. Nevertheless, this little earth is bathed as of old in the sunlight of its Providential Generator. Wide-eyed babes still face the mysteries of physical existence. Men continue to laugh and cry, to love and hate; Some still dream of a nobler world, a fuller life, a more perfect realization. In both the heart and mind of man the gates which lead from mortality to immortality are still ajar. Virtue, love, and idealism are yet the regenerators of humanity. God continues to love and guide the destinies of His creation. The path still winds upward to accomplishment. The soul of man has not been deprived of its wings; they are merely folded under its garment of flesh. Philosophy is ever that magic power which, sundering the vessel of clay, releases the soul from its bondage to habit and perversion. Still as of old, the soul released can spread its wings and soar to the very source of itself.

The criers of the Mysteries speak again, bidding all men welcome to the House of Light. The great institution of materiality has failed. The false civilization built by man has turned, and like the monster of Frankenstein, is destroying its creator. Religion wanders aimlessly in the maze of theological speculation. Science batters itself impotently against the barriers of the unknown. Only transcendental philosophy knows the path. Only the illumined reason can carry the understanding part of man upward to the light. Only philosophy can teach man to be born well, to live well, to die well, and in perfect measure be born again. Into this band of the elect--those who have chosen the life of knowledge, of virtue, and of utility--the philosophers of the ages invite YOU.