The Life and Philosophy of Pythagoras

WHILE Mnesarchus, the father of Pythagoras, was in the city of Delphi on matters pertaining to his business as a merchant, he and his wife, Parthenis, decided to consult the oracle of Delphi as to whether the Fates were favorable for their return voyage to Syria. When the Pythoness (prophetess of Apollo) seated herself on the golden tripod over the yawning vent of the oracle, she did not answer the question they had asked, but told Mnesarchus that his wife was then with child and would give birth to a son who was destined to surpass all men in beauty and wisdom, and who throughout the course of his life would contribute much to the benefit of mankind. Mnesarchus was so deeply impressed by the prophecy that he changed his wife's name to Pythasis, in honor of the Pythian priestess. When the child was born at Sidon in Phnicia, it was--as the oracle had said--a son. Mnesarchus and Pythasis named the child Pythagoras, for they believed that he had been predestined by the oracle.

Many strange legends have been preserved concerning the birth of Pythagoras. Some maintained that he was no mortal man: that he was one of the gods who had taken a human body to enable him to come into the world and instruct the human race. Pythagoras was one of the many sages and saviors of antiquity for whom an immaculate conception is asserted. In his Anacalypsis, Godfrey Higgins writes: "The first striking circumstance in which the history of Pythagoras agrees with the history of Jesus is, that they were natives of nearly the same country; the former being born at Sidon, the latter at Bethlehem, both in Syria. The father of Pythagoras, as well as the father of Jesus, was prophetically informed that his wife should bring forth a son, who should be a benefactor to mankind. They were both born when their mothers were from home on journeys, Joseph and his wife having gone up to Bethlehem to be taxed, and the father of Pythagoras having travelled from Samos, his residence, to Sidon, about his mercantile concerns. Pythais [Pythasis], the mother of Pythagoras, had a connexion with an Apolloniacal spectre, or ghost, of the God Apollo, or God Sol, (of course this must have been a holy ghost, and here we have the Holy Ghost) which afterward appeared to her husband, and told him that he must have no connexion with his wife during her pregnancy--a story evidently the same as that relating to Joseph and Mary. From these peculiar circumstances, Pythagoras was known by the same title as Jesus, namely, the son of God; and was supposed by the multitude to be under the influence of Divine inspiration."

This most famous philosopher was born sometime between 600 and 590 B.C., and the length of his life has been estimated at nearly one hundred years.

The teachings of Pythagoras indicate that he was thoroughly conversant with the precepts of Oriental and Occidental esotericism. He traveled among the Jews and was instructed by the Rabbins concerning the secret traditions of Moses, the lawgiver of Israel. Later the School of the Essenes was conducted chiefly for the purpose of interpreting the Pythagorean symbols. Pythagoras was initiated into the Egyptian, Babylonian, and Chaldean Mysteries. Although it is believed by some that he was a disciple of Zoroaster, it is doubtful whether his instructor of that name was the God-man now revered by the Parsees. While accounts of his travels differ, historians agree that he visited many countries and studied at the feet of many masters.

"After having acquired all which it was possible for him to learn of the Greek philosophers and, presumably, become an initiate in the Eleusinian mysteries, he went to Egypt, and after many rebuffs and refusals, finally succeeded in securing initiation in the Mysteries of Isis, at the hands of the priests of Thebes. Then this intrepid 'joiner' wended his way into Phoenicia and Syria where the Mysteries of Adonis were conferred upon him, and crossing to the valley of the Euphrates he tarried long enough to become versed in, the secret lore of the Chaldeans, who still dwelt in the vicinity of Babylon. Finally, he made his greatest and most historic venture through Media and Persia into Hindustan where he remained several years as a pupil and initiate of the learned Brahmins of Elephanta and Ellora." (See Ancient Freemasonry, by Frank C. Higgins, 32°.) The same author adds that the name of Pythagoras is still preserved in the records of the Brahmins as Yavancharya, the Ionian Teacher.

Pythagoras was said to have been the first man to call himself a philosopher; in fact, the world is indebted to him for the word philosopher. Before that time the wise men had called themselves sages, which was interpreted to mean those who know. Pythagoras was more modest. He coined the word philosopher, which he defined as one who is attempting to find out.

After returning from his wanderings, Pythagoras established a school, or as it has been sometimes called, a university, at Crotona, a Dorian colony in Southern Italy. Upon his arrival at Crotona he was regarded askance, but after a short time those holding important positions in the surrounding colonies sought his counsel in matters of great moment. He gathered around him a small group of sincere disciples whom he instructed in the secret wisdom which had been revealed to him, and also in the fundamentals of occult mathematics, music, and astronomy, which he considered to be the triangular foundation of all the arts and sciences.

When he was about sixty years old, Pythagoras married one of his disciples, and seven children resulted from the union. His wife was a remarkably able woman, who not only inspired him during the years of his life but after his assassination continued to promulgate his doctrines.

As is so often the case with genius, Pythagoras by his outspokenness incurred both political and personal enmity. Among those who came for initiation was one who, because Pythagoras refused to admit him, determined to destroy both the man and his philosophy. By means of false propaganda, this disgruntled one turned the minds of the common people against the philosopher. Without warning, a band of murderers descended upon the little group of buildings where the great teacher and his disciples dwelt, burned the structures and killed Pythagoras.

Accounts of the philosopher's death do not agree. Some say that he was murdered with his disciples; others that, on escaping from Crotona with a small band of followers, he was trapped and burned alive by his enemies in a little house where the band had decided to rest for the night. Another account states that, finding themselves trapped in the burning structure, the disciples threw themselves into the flames, making of their own bodies a bridge over which Pythagoras escaped, only to die of a broken heart a short time afterwards as the result of grieving over the apparent fruitlessness of his efforts to serve and illuminate mankind.

His surviving disciples attempted to perpetuate his doctrines, but they were persecuted on every hand and very little remains today as a testimonial to the greatness of this philosopher. It is said that the disciples of Pythagoras never addressed him or referred to him by his own name, but always as The Master or That Man. This may have been because of the fact that the name Pythagoras was believed to consist of a certain number of specially arranged letters with great sacred significance. The Word magazine has printed an article by T. R. Prater, showing that Pythagoras initiated his candidates by means of a certain formula concealed within

PYTHAGORAS, THE FIRST PHILOSOPHER.

From Historia Deorum Fatidicorum.

During his youth, Pythagoras was a disciple of Pherecydes and Hermodamas, and while in his teens became renowned for the clarity of his philosophic concepts. In height he exceeded six feet; his body was as perfectly formed as that of Apollo. Pythagoras was the personification of majesty and power, and in his presence a felt humble and afraid. As he grew older, his physical power increased rather than waned, so that as he approached the century mark he was actually in the prime of life. The influence of this great soul over those about him was such that a word of praise from Pythagoras filled his disciples with ecstasy, while one committed suicide because the Master became momentarily irritate over something he had dome. Pythagoras was so impressed by this tragedy that he never again spoke unkindly to or about anyone.

the letters of his own name. This may explain why the word Pythagoras was so highly revered.

After the death of Pythagoras his school gradually disintegrated, but those who had benefited by its teachings revered the memory of the great philosopher, as during his life they had reverenced the man himself. As time went on, Pythagoras came to be regarded as a god rather than a man, and his scattered disciples were bound together by their common admiration for the transcendent genius of their teacher. Edouard Schure, in his Pythagoras and the Delphic Mysteries, relates the following incident as illustrative of the bond of fellowship uniting the members of the Pythagorean School:

"One of them who had fallen upon sickness and poverty was kindly taken in by an innkeeper. Before dying he traced a few mysterious signs (the pentagram, no doubt) on the door of the inn and said to the host, 'Do not be uneasy, one of my brothers will pay my debts.' A year afterwards, as a stranger was passing by this inn he saw the signs and said to the host, 'I am a Pythagorean; one of my brothers died here; tell me what I owe you on his account.'"

Frank C. Higgins, 32°, gives an excellent compendium of the Pythagorean tenets in the following outline:

"Pythagoras' teachings are of the most transcendental importance to Masons, inasmuch as they are the necessary fruit of his contact with the leading philosophers of the whole civilized world of his own day, and must represent that in which all were agreed, shorn of all weeds of controversy. Thus, the determined stand made by Pythagoras, in defense of pure monotheism, is sufficient evidence that the tradition to the effect that the unity of God was the supreme secret of all the ancient initiations is substantially correct. The philosophical school of Pythagoras was, in a measure, also a series of initiations, for he caused his pupils to pass through a series of degrees and never permitted them personal contact with himself until they had reached the higher grades. According to his biographers, his degrees were three in number. The first, that of 'Mathematicus,' assuring his pupils proficiency in mathematics and geometry, which was then, as it would be now if Masonry were properly inculcated, the basis upon which all other knowledge was erected. Secondly, the degree of 'Theoreticus,' which dealt with superficial applications of the exact sciences, and, lastly, the degree of 'Electus,' which entitled the candidate to pass forward into the light of the fullest illumination which he was capable of absorbing. The pupils of the Pythagorean school were divided into 'exoterici,' or pupils in the outer grades, and 'esoterici,' after they had passed the third degree of initiation and were entitled to the secret wisdom. Silence, secrecy and unconditional obedience were cardinal principles of this great order." (See Ancient Freemasonry.)

PYTHAGORIC FUNDAMENTALS

The study of geometry, music, and astronomy was considered essential to a rational understanding of God, man, or Nature, and no one could accompany Pythagoras as a disciple who was not thoroughly familiar with these sciences. Many came seeking admission to his school. Each applicant was tested on these three subjects, and if found ignorant, was summarily dismissed.

Pythagoras was not an extremist. He taught moderation in all things rather than excess in anything, for he believed that an excess of virtue was in itself a vice. One of his favorite statements was: "We must avoid with our utmost endeavor, and amputate with fire and sword, and by all other means, from the body, sickness; from the soul, ignorance; from the belly, luxury; from a city, sedition; from a family, discord; and from all things, excess." Pythagoras also believed that there was no crime equal to that of anarchy.

All men know what they want, but few know what they need. Pythagoras warned his disciples that when they prayed they should not pray for themselves; that when they asked things of the gods they should not ask things for themselves, because no man knows what is good for him and it is for this reason undesirable to ask for things which, if obtained, would only prove to be injurious.

The God of Pythagoras was the Monad, or the One that is Everything. He described God as the Supreme Mind distributed throughout all parts of the universe--the Cause of all things, the Intelligence of all things, and the Power within all things. He further declared the motion of God to be circular, the body of God to be composed of the substance of light, and the nature of God to be composed of the substance of truth.

Pythagoras declared that the eating of meat clouded the reasoning faculties. While he did not condemn its use or totally abstain therefrom himself, he declared that judges should refrain from eating meat before a trial, in order that those who appeared before them might receive the most honest and astute decisions. When Pythagoras decided (as he often did) to retire into the temple of God for an extended period of time to meditate and pray, he took with his supply of specially prepared food and drink. The food consisted of equal parts of the seeds of poppy and sesame, the skin of the sea onion from which the juice had been thoroughly extracted, the flower of daffodil, the leaves of mallows, and a paste of barley and peas. These he compounded together with the addition of wild honey. For a beverage he took the seeds of cucumbers, dried raisins (with seeds removed), the flowers of coriander, the seeds of mallows and purslane, scraped cheese, meal, and cream, mixed together and sweetened with wild honey. Pythagoras claimed that this was the diet of Hercules while wandering in the Libyan desert and was according to the formula given to that hero by the goddess Ceres herself.

The favorite method of healing among the Pythagoreans was by the aid of poultices. These people also knew the magic properties of vast numbers of plants. Pythagoras highly esteemed the medicinal properties of the sea onion, and he is said to have written an entire volume on the subject. Such a work, however, is not known at the present time. Pythagoras discovered that music had great therapeutic power and he prepared special harmonies for various diseases. He apparently experimented also with color, attaining considerable success. One of his unique curative processes resulted from his discovery of the healing value of certain verses from the Odyssey and the Iliad of Homer. These he caused to be read to persons suffering from certain ailments. He was opposed to surgery in all its forms and also objected to cauterizing. He would not permit the disfigurement of the human body, for such, in his estimation, was a sacrilege against the dwelling place of the gods.

Pythagoras taught that friendship was the truest and nearest perfect of all relationships. He declared that in Nature there was a friendship of all for all; of gods for men; of doctrines one for another; of the soul for the body; of the rational part for the irrational part; of philosophy for its theory; of men for one another; of countrymen for one another; that friendship also existed between strangers, between a man and his wife, his children, and his servants. All bonds without friendship were shackles, and there was no virtue in their maintenance. Pythagoras believed that relationships were essentially mental rather than physical, and that a stranger of sympathetic intellect was closer to him than a blood relation whose viewpoint was at variance with his own. Pythagoras defined knowledge as the fruitage of mental accumulation. He believed that it would be obtained in many ways, but principally through observation. Wisdom was the understanding of the source or cause of all things, and this could be secured only by raising the intellect to a point where it intuitively cognized the invisible manifesting outwardly through the visible, and thus became capable of bringing itself en rapport with the spirit of things rather than with their forms. The ultimate source that wisdom could cognize was the Monad, the mysterious permanent atom of the Pythagoreans.

Pythagoras taught that both man and the universe were made in the image of God; that both being made in the same image, the understanding of one predicated the knowledge of the other. He further taught that there was a constant interplay between the Grand Man (the universe) and man (the little universe).

Pythagoras believed that all the sidereal bodies were alive and that the forms of the planets and stars were merely bodies encasing souls, minds, and spirits in the same manner that the visible human form is but the encasing vehicle for an invisible spiritual organism which is, in reality, the conscious individual. Pythagoras regarded the planets as magnificent deities, worthy of the adoration and respect of man. All these deities, however, he considered subservient to the One First Cause within whom they all existed temporarily, as mortality exists in the midst of immortality.

The famous Pythagorean Υ signified the power of choice and was used in the Mysteries as emblematic of the Forking of the Ways. The central stem separated into two parts, one branching to

THE SYMMETRICAL GEOMETRIC SOLIDS.

To the five symmetrical solids of the ancients is added the sphere (1), the most perfect of all created forms. The five Pythagorean solids are: the tetrahedron (2) with four equilateral triangles as faces; the cube (3) with six squares as faces; the octahedron (4) with eight equilateral triangles as faces; the icosahedron (5) with twenty equilateral triangles as faces; and the dodecahedron (6) with twelve regular pentagons as faces.

the right and the other to the left. The branch to the right was called Divine Wisdom and the one to the left Earthly Wisdom. Youth, personified by the candidate, walking the Path of Life, symbolized by the central stem of the Υ, reaches the point where the Path divides. The neophyte must then choose whether he will take the left-hand path and, following the dictates of his lower nature, enter upon a span of folly and thoughtlessness which will inevitably result in his undoing, or whether he will take the right-hand road and through integrity, industry, and sincerity ultimately regain union with the immortals in the superior spheres.

It is probable that Pythagoras obtained his concept of the Υ from the Egyptians, who included in certain of their initiatory rituals a scene in which the candidate was confronted by two female figures. One of them, veiled with the white robes of the temple, urged the neophyte to enter into the halls of learning; the other, bedecked with jewels, symbolizing earthly treasures, and bearing in her hands a tray loaded with grapes (emblematic of false light), sought to lure him into the chambers of dissipation. This symbol is still preserved among the Tarot cards, where it is called The Forking of the Ways. The forked stick has been the symbol of life among many nations, and it was placed in the desert to indicate the presence of water.

Concerning the theory of transmigration as disseminated by Pythagoras, there are differences of opinion. According to one view, he taught that mortals who during their earthly existence had by their actions become like certain animals, returned to earth again in the form of the beasts which they had grown to resemble. Thus, a timid person would return in the form of a rabbit or a deer; a cruel person in the form of a wolf or other ferocious animal; and a cunning person in the guise of a fox. This concept, however, does not fit into the general Pythagorean scheme, and it is far more likely that it was given in an allegorical rather than a literal sense. It was intended to convey the idea that human beings become bestial when they allow themselves to be dominated by their own lower desires and destructive tendencies. It is probable that the term transmigration is to be understood as what is more commonly called reincarnation, a doctrine which Pythagoras must have contacted directly or indirectly in India and Egypt.

The fact that Pythagoras accepted the theory of successive reappearances of the spiritual nature in human form is found in a footnote to Levi's History of Magic: "He was an important champion of what used to be called the doctrine of metempsychosis, understood as the soul's transmigration into successive bodies. He himself had been (a) Aethalides, a son of Mercury; (b) Euphorbus, son of Panthus, who perished at the hands of Menelaus in the Trojan war; (c) Hermotimus, a prophet of Clazomenae, a city of Ionia; (d) a humble fisherman; and finally (e) the philosopher of Samos."

Pythagoras also taught that each species of creatures had what he termed a seal, given to it by God, and that the physical form of each was the impression of this seal upon the wax of physical substance. Thus each body was stamped with the dignity of its divinely given pattern. Pythagoras believed that ultimately man would reach a state where he would cast off his gross nature and function in a body of spiritualized ether which would be in juxtaposition to his physical form at all times and which might be the eighth sphere, or Antichthon. From this he would ascend into the realm of the immortals, where by divine birthright he belonged.

Pythagoras taught that everything in nature was divisible into three parts and that no one could become truly wise who did not view every problem as being diagrammatically triangular. He said, "Establish the triangle and the problem is two-thirds solved"; further, "All things consist of three." In conformity with this viewpoint, Pythagoras divided the universe into three parts, which he called the Supreme World, the Superior World, and the Inferior World. The highest, or Supreme World, was a subtle, interpenetrative spiritual essence pervading all things and therefore the true plane of the Supreme Deity itself, the Deity being in every sense omnipresent, omniactive, omnipotent, and omniscient. Both of the lower worlds existed within the nature of this supreme sphere.

The Superior World was the home of the immortals. It was also the dwelling place of the archetypes, or the seals; their natures in no manner partook of the material of earthiness, but they, casting their shadows upon the deep (the Inferior World), were cognizable only through their shadows. The third, or Inferior World, was the home of those creatures who partook of material substance or were engaged in labor with or upon material substance. Hence, this sphere was the home of the mortal gods, the Demiurgi, the angels who labor with men; also the dæmons who partake of the nature of the earth; and finally mankind and the lower kingdoms, those temporarily of the earth but capable of rising above that sphere by reason and philosophy.

The digits 1 and 2 are not considered numbers by the Pythagoreans, because they typify the two supermundane spheres. The Pythagorean numbers, therefore, begin with 3, the triangle, and 4, the square. These added to the 1 and the 2, produce the 10, the great number of all things, the archetype of the universe. The three worlds were called receptacles. The first was the receptacle of principles, the second was the receptacle of intelligences, and the third, or lowest, was the receptacle of quantities.

"The symmetrical solids were regarded by Pythagoras, and by the Greek thinkers after him, as of the greatest importance. To be perfectly symmetrical or regular, a solid must have an equal number of faces meeting at each of its angles, and these faces must be equal regular polygons, i. e., figures whose sides and angles are all equal. Pythagoras, perhaps, may be credited with the great discovery that there are only five such solids.* * *

'Now, the Greeks believed the world [material universe] to be composed of four elements--earth, air, fire, water--and to the Greek mind the conclusion was inevitable that the shapes of the particles of the elements were those of the regular solids. Earth-particles were cubical, the cube being the regular solid possessed of greatest stability; fire-particles were tetrahedral, the tetrahedron being the simplest and, hence, lightest solid. Water-particles were icosahedral for exactly the reverse reason, whilst air-particles, as intermediate between the two latter, were octahedral. The dodecahedron was, to these ancient mathematicians, the most mysterious of the solids; it was by far the most difficult to construct, the accurate drawing of the regular pentagon necessitating a rather elaborate application of Pythagoras' great theorem. Hence the conclusion, as Plato put it, that 'this (the regular dodecahedron) the Deity employed in tracing the plan of the Universe.' (H. Stanley Redgrove, in Bygone Beliefs.)

Mr. Redgrove has not mentioned the fifth element of the ancient Mysteries, that which would make the analogy between the symmetrical solids and the elements complete. This fifth element, or ether, was called by the Hindus akasa. It was closely correlated with the hypothetical ether of modern science, and was the interpenetrative substance permeating all of the other elements and acting as a common solvent and common denominator of them. The twelve-faced solid also subtly referred to the Twelve Immortals who surfaced the universe, and also to the twelve convolutions of the human brain--the vehicles of those Immortals in the nature of man.

While Pythagoras, in accordance with others of his day, practiced divination (possibly arithmomancy), there is no accurate information concerning the methods which he used. He is believed to have had a remarkable wheel by means of which he could predict future events, and to have learned hydromancy from the Egyptians. He believed that brass had oracular powers, because even when everything was perfectly still there was always a rumbling sound in brass bowls. He once addressed a prayer to the spirit of a river and out of the water arose a voice, "Pythagoras, I greet thee." It is claimed for him that he was able to cause dæmons to enter into water and disturb its surface, and by means of the agitations certain things were predicted.

After having drunk from a certain spring one day, one of the Masters of Pythagoras announced that the spirit of the water had just predicted that a great earthquake would occur the next day--a prophecy which was fulfilled. It is highly probable that Pythagoras possessed hypnotic power, not only over man but also over animals. He caused a bird to change the course of its flight, a bear to cease its ravages upon a community, and a bull to change its diet, by the exercise of mental influence. He was also gifted with second sight, being able to see things at a distance and accurately describe incidents that had not yet come to pass.

THE SYMBOLIC APHORISMS OF PYTHAGORAS

Iamblichus gathered thirty-nine of the symbolic sayings of Pythagoras and interpreted them. These have been translated from the Greek by Thomas Taylor. Aphorismic statement was one of the favorite methods of instruction used in the Pythagorean university of Crotona. Ten of the most representative of these aphorisms are reproduced below with a brief elucidation of their concealed meanings.

I. Declining from the public ways, walk in unfrequented paths. By this it is to be understood that those who desire wisdom must seek it in solitude.

NUMBER RELATED TO FORM.

Pythagoras taught that the dot symbolized the power of the number 1, the line the power of the number 2, the surface the power of the number 3, and the solid the power of the number 4.

II. Govern your tongue before all other things, following the gods. This aphorism warns man that his words, instead of representing him, misrepresent him, and that when in doubt as to what he should say, he should always be silent.

III. The wind blowing, adore the sound. Pythagoras here reminds his disciples that the fiat of God is heard in the voice of the elements, and that all things in Nature manifest through harmony, rhythm, order, or procedure the attributes of the Deity.

IV. Assist a man in raising a burden; but do not assist him in laying it down. The student is instructed to aid the diligent but never to assist those who seek to evade their responsibilities, for it is a great sin to encourage indolence.

V. Speak not about Pythagoric concerns without light. The world is herein warned that it should not attempt to interpret the mysteries of God and the secrets of the sciences without spiritual and intellectual illumination.

VI. Having departed from your house, turn not back, for the furies will be your attendants. Pythagoras here warns his followers that any who begin the search for truth and, after having learned part of the mystery, become discouraged and attempt to return again to their former ways of vice and ignorance, will suffer exceedingly; for it is better to know nothing about Divinity than to learn a little and then stop without learning all.

VII. Nourish a cock, but sacrifice it not; for it is sacred to the sun and moon. Two great lessons are concealed in this aphorism. The first is a warning against the sacrifice of living things to the gods, because life is sacred and man should not destroy it even as an offering to the Deity. The second warns man that the human body here referred to as a cock is sacred to the sun (God) and the moon (Nature), and should be guarded and preserved as man's most precious medium of expression. Pythagoras also warned his disciples against suicide.

VIII. Receive not a swallow into your house. This warns the seeker after truth not to allow drifting thoughts to come into his mind nor shiftless persons to enter into his life. He must ever surround himself with rationally inspired thinkers and with conscientious workers.

IX. Offer not your right hand easily to anyone. This warns the disciple to keep his own counsel and not offer wisdom and knowledge (his right hand) to such as are incapable of appreciating them. The hand here represents Truth, which raises those who have fallen because of ignorance; but as many of the unregenerate do not desire wisdom they will cut off the hand that is extended in kindness to them. Time alone can effect the redemption of the ignorant masses

X. When rising from the bedclothes, roll them together, and obliterate the impression of the body. Pythagoras directed his disciples who had awakened from the sleep of ignorance into the waking state of intelligence to eliminate from their recollection all memory of their former spiritual darkness; for a wise man in passing leaves no form behind him which others less intelligent, seeing, shall use as a mold for the casting of idols.

The most famous of the Pythagorean fragments are the Golden Verses, ascribed to Pythagoras himself, but concerning whose authorship there is an element of doubt. The Golden Verses contain a brief summary of the entire system of philosophy forming the basis of the educational doctrines of Crotona, or, as it is more commonly known, the Italic School. These verses open by counseling the reader to love God, venerate the great heroes, and respect the dæmons and elemental inhabitants. They then urge man to think carefully and industriously concerning his daily life, and to prefer the treasures of the mind and soul to accumulations of earthly goods. The verses also promise man that if he will rise above his lower material nature and cultivate self-control, he will ultimately be acceptable in the sight of the gods, be reunited with them, and partake of their immortality. (It is rather significant to note that Plato paid a great price for some of the manuscripts of Pythagoras which had been saved from the destruction of Crotona. See Historia Deorum Fatidicorum, Geneva, 1675.)

PYTHAGOREAN ASTRONOMY

According to Pythagoras, the position of each body in the universe was determined by the essential dignity of that body. The popular concept of his day was that the earth occupied the center of the solar system; that the planets, including the sun and moon, moved about the earth; and that the earth itself was flat and square. Contrary to this concept, and regardless of criticism, Pythagoras declared that fire was the most important of all the elements; that the center was the most important part of every body; and that, just as Vesta's fire was in the midst of every home, so in the midst of the universe was a flaming sphere of celestial radiance. This central globe he called the Tower of Jupiter, the Globe of Unity, the Grand Monad, and the Altar of Vesta. As the sacred number 10 symbolized the sum of all parts and the completeness of all things, it was only natural for Pythagoras to divide the universe into ten spheres, symbolized by ten concentric circles. These circles began at the center with the globe of Divine Fire; then came the seven planers, the earth, and another mysterious planet, called Antichthon, which was never visible.

Opinions differ as to the nature of Antichthon. Clement of Alexandria believed that it represented the mass of the heavens; others held the opinion that it was the moon. More probably it was the mysterious eighth sphere of the ancients, the dark planet which moved in the same orbit as the earth but which was always concealed from the earth by the body of the sun, being in exact opposition to the earth at all times. Is this the mysterious Lilith concerning which astrologers have speculated so long?

Isaac Myer has stated: "The Pythagoreans held that each star was a world having its own atmosphere, with an immense extent surrounding it, of aether." (See The Qabbalah.) The disciples of Pythagoras also highly revered the planet Venus, because it was the only planet bright enough to cast a shadow. As the morning star, Venus is visible before sunrise, and as the evening star it shines forth immediately after sunset. Because of these qualities, a number of names have been given to it by the ancients. Being visible in the sky at sunset, it was called vesper, and as it arose before the sun, it was called the false light, the star of the morning, or Lucifer, which means the light-bearer. Because of this relation to the sun, the planet was also referred to as Venus, Astarte, Aphrodite, Isis, and The Mother of the Gods. It is possible that: at some seasons of the year in certain latitudes the fact that Venus was a crescent could be detected without the aid of a telescope. This would account for the crescent which is often seen in connection with the goddesses of antiquity, the stories of which do not agree with the phases of the moon. The accurate knowledge which Pythagoras possessed concerning astronomy he undoubtedly secured in the Egyptian temples, for their priests understood the true relationship of the heavenly bodies many thousands of years before that knowledge was revealed to the uninitiated world. The fact that the knowledge he acquired in the temples enabled him to make assertions requiring two thousand years to check proves why Plato and Aristotle so highly esteemed the profundity of the ancient Mysteries. In the midst of comparative scientific ignorance, and without the aid of any modern instruments, the priest-philosophers had discovered the true fundamentals of universal dynamics.

An interesting application of the Pythagorean doctrine of geometric solids as expounded by Plato is found in The Canon. "Nearly all the old philosophers," says its anonymous author, "devised an harmonic theory with respect to the universe, and the practice continued till the old mode of philosophizing died out. Kepler (1596), in order to demonstrate the Platonic doctrine, that the universe was formed of the five regular solids, proposed the following rule. 'The earth is a circle, the measurer of all. Round it describe a dodecahedron; the circle inclosing this will be Mars. Round Mars describe a tetrahedron; the sphere inclosing this will be Jupiter. Describe a cube round Jupiter; the sphere containing this will be Saturn. Now inscribe in the earth an icosahedron; the circle inscribed in it will be Venus. Inscribe an octahedron in Venus; the circle inscribed in it will be Mercury' (Mysterium Cosmographicum, 1596). This rule cannot be taken seriously as a real statement of the proportions of the cosmos, fox it bears no real resemblance to the ratios published by Copernicus in the beginning of the sixteenth century. Yet Kepler was very proud of his formula, and said he valued it more than the Electorate of Saxony. It was also approved by those two eminent authorities, Tycho and Galileo, who evidently understood it. Kepler himself never gives the least hint of how his precious rule is to be interpreted." Platonic astronomy was not concerned with the material constitution or arrangement of the heavenly bodies, but considered the stars and planers primarily as focal points of Divine intelligence. Physical astronomy was regarded as the science of "shadows," philosophical astronomy the science of "realities."

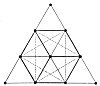

THE TETRACTYS.

Theon of Smyrna declares that the ten dots, or tetractys of Pythagoras, was a symbol of the greatest importance, for to the discerning mind it revealed the mystery of universal nature. The Pythagoreans bound themselves by the following oath: "By Him who gave to our soul the tetractys, which hath the fountain and root of ever-springing nature."

By connecting the ten dots of the tetractys, nine triangles are formed. Six of these are involved in the forming of the cube. The same triangles, when lines are properly drawn between them, also reveal the six-pointed star with a dot in the center. Only seven dots are used in forming the cube and the star. Qabbalistically, the three unused corner dots represent the threefold, invisible causal nature of the universe, while the seven dots involved in the cube and the star are the Elohim--the Spirits of the seven creative periods. The Sabbath, or seventh day, is the central dot.