Stephen Dafoe Challenged Freemasonry

To Shape Up Or Die Years Ago

By Wor. Bro. Frederic L. Milliken

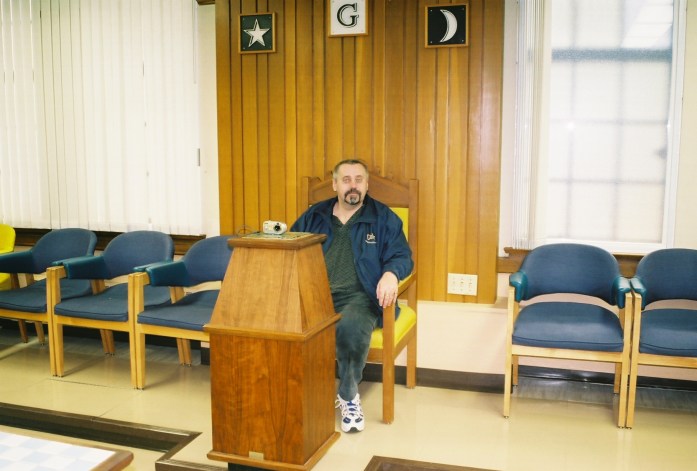

Stephen Dafoe

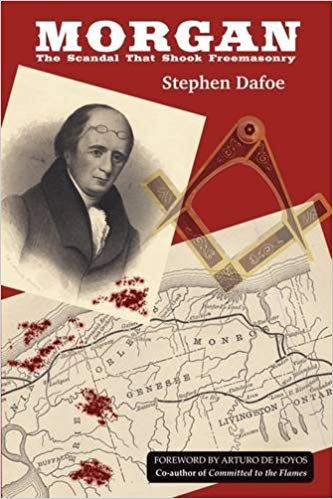

Masonic researcher, author, speaker, video producer, journalist and historian Stephen Dafoe has chronicled the decline of American Freemasonry for years. His research has been published in The Scottish Rite Journal, Heredom (the Transactions of the Scottish Rite Research Society), Templar History Magazine, Knight Templar Magazine, The Fourth Part Of A Circle, Masonic Magazine and The Masonic Society Journal among others. He has even gone back into history to write the definitive work on the Morgan Affair with his book “Morgan: The Scandal That Shook Freemasonry,” a time in American History when half of all Freemasonry closed its doors. Now that was Masonic decline!

His more modern assessment of Masonic decline was published in 2007 when he wrote the article and produced the video:

The Restaurant At The End Of The Masonic Universe

View the YouTube video at the link below:

In 2009 Dafoe wrote:

There’s a Hole in Our Bucket

North American Freemasonry is on a bit of an infinite loop these days. I don’t mean the type of infinite loop we used to see on the Flintstones whenever Fred and Barney would drive past the same three houses and two palm trees over and over again, but it is close. The type of infinite-loop motif I’m referring to is the type that forms the basis of songs like 99 Bottle of Beer or There’s a Hole in my Bucket. In fact, both songs represent two of the problems confronting many lodges today with respect to our declining membership.

Now, before you turn the page, let me assure you this is not another article lamenting our sagging numbers, nor is it a rallying call for us to rise towards that lofty Masonic pinnacle that was the Halcyon Days of the post-World War II influx. But we will be looking at the numbers, not with an eye towards depression, but with an eye towards resolution. We have a problem, but if we can truly know where the problem lies, and if we can convince enough Masons that this is actually the case, we can collectively begin to work towards fixing it.

What the numbers tell us:

Since 1925, the Masonic Service Association of North America (MSANA) has been keeping track of the numbers of Freemasons in the United States.

Without launching into a long and boring examination of the ebb and flow of these numbers, let it suffice to say that Masonic membership’s highest point in terms of numbers was 1959, when it boasted 4,103,161 members; its lowest point occurring in 2007, when our ranks had been reduced to just 1,483,449. Ironically, our highest point in terms of membership may well have been our lowest point for Freemasonry, or at least the start of it.

The hand ringers in our fraternity love to hold on to that 1959 membership number like the middle aged bachelor who holds onto the photo of the fashion model he dated in college, as if it were a goal he may yet attain once more. But as both pine away for a desire that has longed since passed the realm of possibility, they begin to tell themselves lies to justify their current situation.

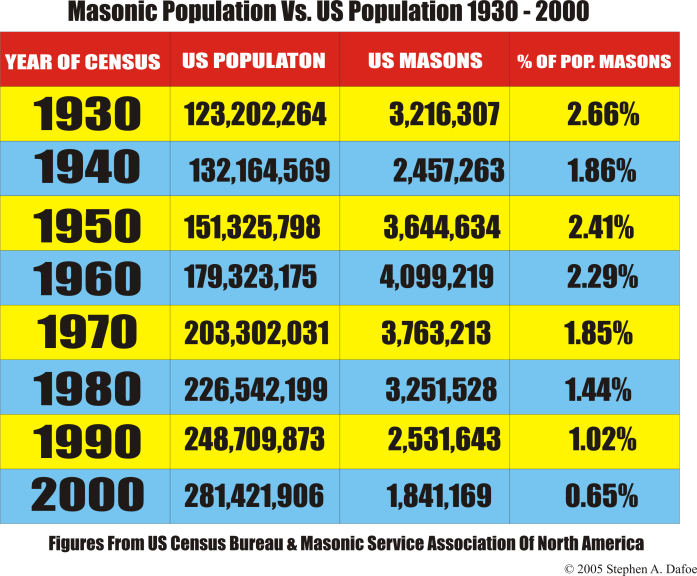

As such, our hand ringers have created a long-standing belief that once upon a time Freemasons made up a sizable percentage of the population in American communities. However, if one compares the US census with the MSANA membership statistics, an interesting and revealing picture emerges. In 1930, only 2.66 per cent of the population belonged to the Masonic fraternity. By 1940, that percentage had been reduced to 1.86% – largely due to the effects of the Great Depression, men simply couldn’t afford their dues. It reached its lowest point in 2000, when less than 1 per cent of the US population could say they owned a Masonic apron. But even in the midst of those glory days our hand ringers so love to remind us about, only 2.41 per cent of the population belonged to the Craft. If we divide and multiply these figures to represent a male population of roughly 50 per cent, then we see that even at our highest percentile penetration in 1930, only 5 in 100 American males were Freemasons – this is a far cry from the cries of deep lamentation emanating from the lips of our loudest hand ringing Brethren that once upon a time almost every American male was a mason. And yet, they will cling to that four-million-plus-Masons figure like cat hair to black pants, failing to accept that the much brandied about number represents nothing more than a sociological anomaly. It was that influx of men who swelled the Craft’s ranks between 1945 and 1959 that, in many ways set the tone for the downward spiral towards the Masonic caliginosity we have experienced in the decades since. Although many became dedicated members of the Craft, expanding their learning through books and periodicals, discussions and debates, many who took on leadership rules were attracted by the formality of the ritual, to the point where it became the beginning and end of a Master Mason’s education.

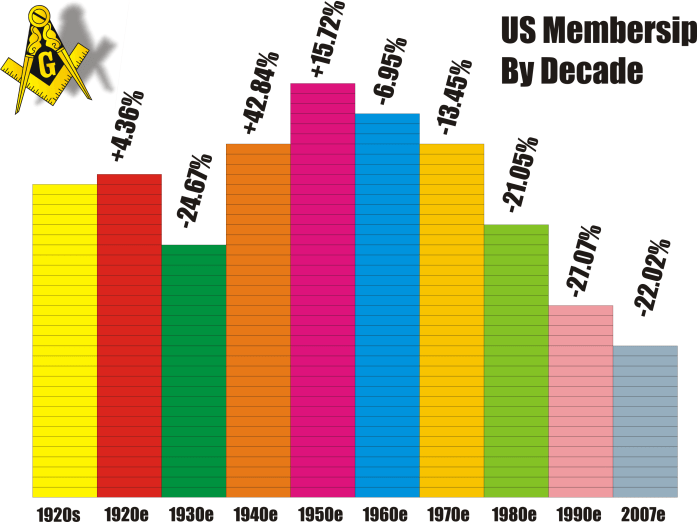

Perhaps the greatest decade for Freemasonry – at least from a point of research, education and all around Masonic bigness – was the 1920’s; a decade that saw the creation of the National Masonic Research Society and its publication The Builder, a magazine that offered the words and thoughts of the great Masonic luminaries of the day. It was also a decade where Masons displayed their Masonic pride, not by the number of pins on their lapels, but by the number of elegant buildings on Main Street. It was during the 1920’s that great Masonic buildings including the House of the Temple in Washington DC, The George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia and the Detroit Masonic Temple in Michigan transformed from idea to reality. That decade, which I’ve long-argued to be the most enlightening for Freemasonry, saw an increase in membership of just above four per cent.

But then the Great Depression reduced membership roles by almost 25 per cent by then end of the 1930’s. In fact membership continued to decline until America entered the Second World War in 1941, and that is when the anomaly occurred. By the end of the 1940’s, Masonic membership had increased by more than 42 percent, carrying a forward momentum through most of the 1950’s, which saw an increase of 16 percent from the decade before. From this point on membership has been on a steady decline, with the present decade – now about to enter its final year – on a fast track to surpassing the 1990’s, the current record holder for membership seepage.

It is a mistake for us to pine away for a resurgence of the anomaly that was the 1940’s and 1950’s. The WWII soldier returned home and, looking for the camaraderie of the barracks, he sought to find it in fraternal societies like Freemasonry. This inflated our membership roles like a windfall inflates a bank account, but like the lottery winner who does not invest his new found money properly; it is soon piddled away until nothing remains.

Another tale the hand ringers love to tell us, especially those who have more steps behind them than they have left ahead of them, is that men are not joining today like they used to, and that we are losing members from death faster than we can replace them through initiations. Certainly, if one considers “not joining like they used to” to be those post-war Halcyon Days previously discussed, then I’m more than willing to concede the point. However, if there is one myth in Freemasonry that has gained wide currency and firm traction, it is the notion that Masons are dying faster than we can replace them.

What the numbers don’t tell us!

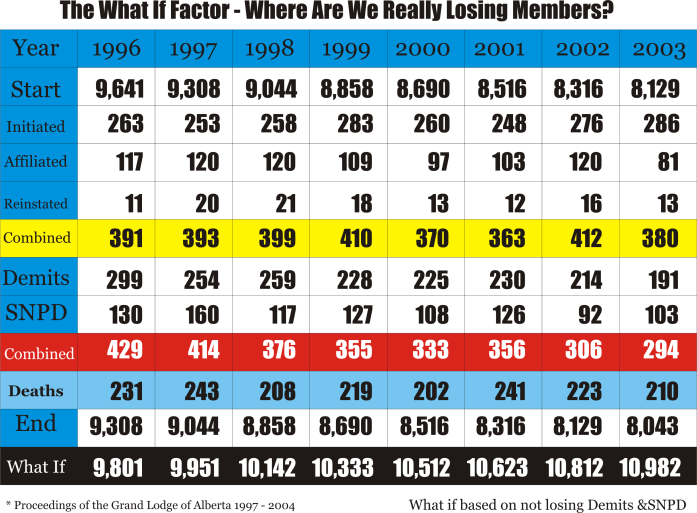

In 2005 I was asked to deliver the keynote address to the Western Canada Conference – an annual gathering of the Grand lines of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Part of my presentation sought to dispel this myth that the Grim Reaper was using his scythe to cut a swath through the fraternity. Whereas, the MSANA numbers only give us the annual bottom line, I was able to look at the big picture closer to home by tracking specifics in our membership statistics over an eight-year period.

What I discovered was that, like the rest of North America, Alberta had a sizable hole in our Masonic bucket; 1,777 of our Brethren had affiliated with the Grand Lodge above, leaving us with a net loss of 1,512 members between 1996 and 2003. But this is not where our problem was because the numbers showed that in that same period of time, 3,118 men had joined, affiliated or renewed their membership in one of our lodges.

In an ideal world, the difference between deaths and new members should have seen Alberta experience a 14 per cent growth in that time, but instead we were dwindling, just like everywhere else. The question was why? Where was the hole in our Masonic bucket that was causing the decline? It wasn’t through deaths; we were clearly finding the men to replace ourselves. The answer was through demits and suspensions for non payment of dues (SNPD); a combined loss of 2,863 over the eight years. When added to the deaths, we had lost a total of 4,640 men, while gaining a respectable 3,118. The hole in our Masonic bucket had been found and, as I’ve learned, it is not an isolated situation.

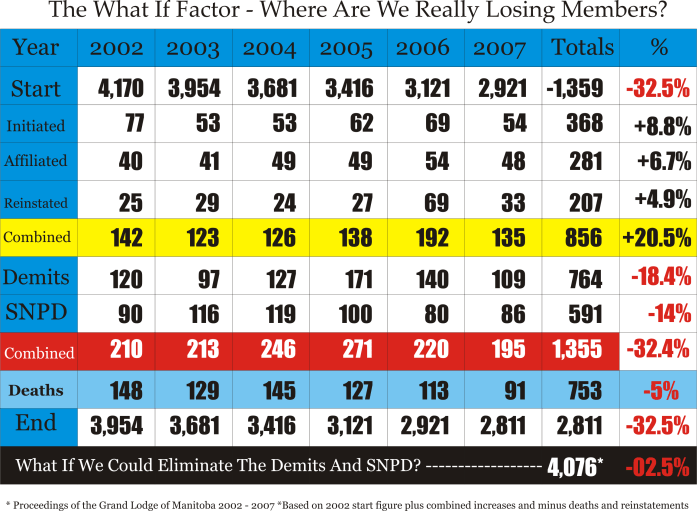

This past November I was keynote speaker at the Grand Lodge of Manitoba’s Masonic workshop and presented a similar address and findings, chronicling their past six years of data. Like Alberta, Manitoba has a hole in its Masonic bucket, caused by demits and suspensions outpacing new members. Between 2002 and 2007 Manitoba saw 856 men join, affiliate or reinstate their memberships. During that same time, 753 Manitoba Masons have died; again leaving a positive number between membership losses and gains. Like Alberta, their hole is caused by the combination of demits and SNPD’s. In the past six years the province has seen 1,355 men leave the Masonic fraternity.

But the Craft lodge in Canada is not alone in finding it has a bucket with the same hole.

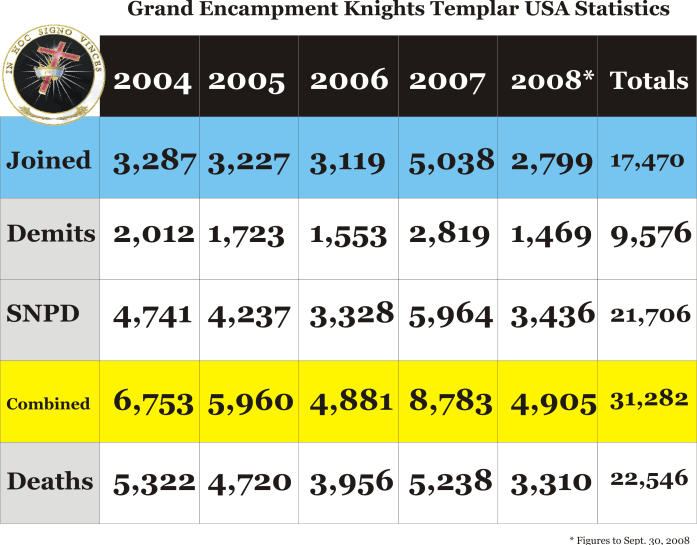

Membership statistics from the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar show that between 2004 and the end of September 2008, 17,470 American Freemasons have become Templars, while 9,576 have taken a demit and another 21,706 have been suspended for non payment of dues. Add to this the 22,546 Templars who have gone on to join their creator, and you have 36,358 fewer Knights Templar marching about. But perhaps marching about is precisely the problem. Perhaps the men who are joining today are joining to parade about like the sword-wielding Templars of old and disappointed to find only old Templars parading about doing sword drill. It is a question only the Grand Encampment and those who are left remain in her Commanderies can resolve, but like the Craft Lodges, its bucket is leaking primarily from the same rusted out hole.

Towards a solution

Back when I was editor of the short-lived Masonic Magazine, I wrote an editorial titled The Restaurant at the End of the Masonic Universe. Without republishing the editorial here, it told the story of a restaurant that does not live up to its advertising slogan, “We make good food better,” an obvious play on our own slogan “We take good men and make them better.” The editorial, which has received equal doses of praise and criticism, sought to explain in a light manner the malaise affecting Freemasonry today and the true cause for the hole in our bucket.

Every mason has heard the expression “but we’ve always done it that way before.” The fact that it is used as the butt of Masonic jokes serves as proof positive of its longevity and power in maintaining a status quo. But, as we have seen by what the MSANA numbers don’t show us, the status quo is draining our buckets. As the allegory of my restaurant editorial showed, the reason things suck in many lodges is because the men who show up month after month like things that suck. They do so because they enjoy the bland food; not the shoe-leather roast beef and off color green beans, but the Masonic meal that is largely comprised of recitation of minutes, tedious debates over how funds are dispersed and arguments over when and how to salute the Worshipful Master. Clearly these are not the things that appeal to the men who are leaving our ranks. If they were, they’d be with us still. But instead of spending our energies trying to retain them, we devote our efforts to finding their replacements.

For as long as I have been a Freemason, we have been trying to fill a bucket that has a sizable hole in it. Like Henry in the famed children’s song, we have whined through the infinite loop of reasons why we can’t fix the bucket and like Jack in the classic nursery rhyme, have rolled down the hill, our empty bucket tumbling behind us. Like children on a bus trip we have done our rendition of 99 Bottle of Beer by repeating the same pattern ad nausea, as one by one our members – like the bottles of beer on the wall – vanish.

Unfortunately, we are not doing a good enough job identifying what it is that the men who are joining are looking for, which is – in almost all cases – that which they cannot get any place else – FREEMASONRY! They are looking to be educated in the Masonic Craft, in the art of being a gentleman in a world that has largely forgotten what one was, and in how they can be part of – to quote my jurisdiction’s ritual – “the society of men who prize honor and virtue above the external advantages of rank and fortune.” In short, they want to be taught the things about themselves and the world in which they live that only Freemasonry can teach them. If we cannot teach them because we do not know these things ourselves, then we must learn alongside them. Then, and only then, can the hole in our Masonic bucket be truly repaired and we can return to that growth that once allowed us to select men who would most benefit from Freemasonry’s teaching and most benefit Freemasonry by their character and their conduct.

It will not be and easy task fixing this half-century old hole in our Masonic bucket; but it will not be possible at all until we accept that a failure to do so is the cause of our decline and the harbinger of our demise.

This article originally appeared in Issue 2 of The Masonic Society Journal.

All rights reserved and copyrighted. Permission of the author is required to reprint any and all parts of this article.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

So have we fixed the hole in our Masonic Bucket yet? Have we taken our decline seriously yet? Or are we sticking our fingers in a dike about to burst and putting band aids on a wound that needs stitches? When are we going to stop the bleeding?

The way I see it is that Freemasonry has become a Top Down Society. And there lies our problem. Because all Freemasonry is local and used to be that way and operated successfully that way. But today Grand Lodge wants to micromanage the Fraternity.. Top Down Freemasonry creates conflict, too much conflict. It stifles creativity, it crushes enthusiasm and ruins pride in the Craft. One size does not fit all in Freemasonry. We have turned our beloved Craft into a copy of the US Army. It is time for the younger Masons, those thirsty FOR THE REAL THING to organize and start telling Grand Lodge NO!

Grand Lodges in their infinite wisdom are trying to market Freemasonry while allowing the product itself to deteriorate. Like the restaurant at the end of the Masonic universe grandiose words are no substitute for an inferior product. Improve the product and it will sell itself. What we really have is a problem of retention not a membership problem. And that lies in the fact that our promises don’t live up to expectations.

We have literally knocking on our doors the next generation who are thirsty for a philosophy they can sink their teeth into. These are not superficial party goers but rather men who are seekers, searchers for a way to make a difference in this fractured world of ours. They don’t mind working hard for the goals ahead. We shouldn’t be making things easy and less expensive for them, just the opposite. We should be demanding much of them and they expecting the same from us in return. The question is are we going to give them pablum or are we going to give them the real thing, Freemasonry… Frederic L. Milliken