Freemasonry Among the Five Tribes

By T.S. Akers

Oklahoma is a Choctaw word meaning “red people.” The name

was first proposed by Choctaw Principal Chief Allen Wright during treaty

negotiations with the federal government in 1866.[i]

Wright’s suggestion was employed by the Brethren of Oklahoma Lodge No. 217

when that Lodge was chartered in 1868.[ii]

The region that became Oklahoma was originally home to

the Caddo, Osage, and Wichita Nations. Cherokees who had voluntarily

migrated to Arkansas in 1812, would periodically cross into Osage country,

leading to an ongoing feud between the two tribes. This caused Col.

Matthew Arbuckle to move elements of the 7th US Infantry

Regiment west from Fort Smith in 1824 to establish a post at the

confluence of the Grand and Arkansas Rivers, in order to maintain peace on

the frontier.[iii]

The establishment of Fort Gibson by Arbuckle, a Freemason, ushered in the

arrival of Freemasonry in the region.[iv]

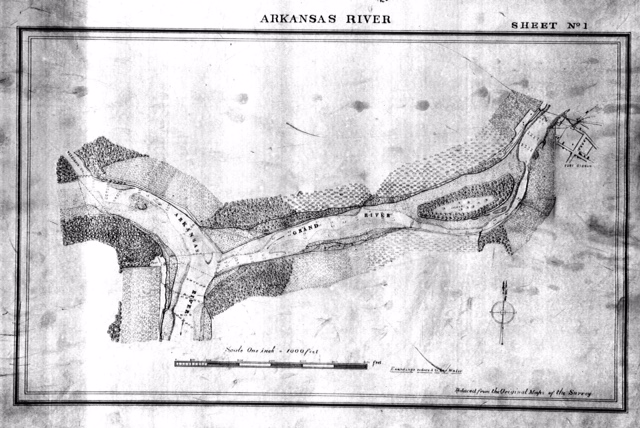

Early map of the Arkansas River, illustrating the location of

Fort Gibson

(Courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society)

While some Choctaw and Chickasaw hunting parties regularly

came to what would become the Indian Territory in pursuit of buffalo, the

first full scale emigration of the Five Tribes occurred in 1827 when roughly

700 Creeks led by Chilly McIntosh made their way west in the wake of the

Treaty of Indian Springs. Known as the McIntosh Party for their support of

Chief William McIntosh in his ceding of Creek lands for land west of the

Mississippi, these Creeks settled in the Three Forks area near Fort Gibson.[v]

The Western or Old Settler Cherokees were removed from Arkansas the

following year.

[vi] It is estimated that the Indian Removal Act of 1830 would

see over 58,000 members of the Five Tribes either emigrate or be forcibly

removed to the Indian Territory.

The Five Tribes were, as they remain today, sovereign

nations. This required the United States to enter into treaties with the

Five Tribes, which often made travel to Washington, DC, necessary for tribal

headmen. For the mixed bloods that dominated tribal politics, this

interaction with white culture was not foreign. The Cherokee William P.

Ross, the Choctaw Peter Pitchlynn, and the Creek Chilly McIntosh were all of

Scottish descent. It was on a diplomatic visit to Washington, DC, that

William P. Ross was made a Freemason at Federal Lodge No. 1 in 1848.[vii]

Pitchlynn would also become a Freemason in Washington, DC, and both he and

Ross became Royal Arch Masons there.[viii]

The 1839 Act of Union brought together the Western Cherokees,

formerly of Arkansas, and the recently removed Cherokees as the Cherokee

Nation, establishing their capital at Tahlequah.[ix]

It was here on November 9, 1848, that Cherokee Lodge No. 21 was chartered by

the Grand Lodge of Arkansas. The first Lodge Secretary was William P. Ross.

Additional Lodges, with primarily indigenous membership, that were chartered

included Choctaw Lodge No. 52, Flint Lodge No. 74, and Muscogee Lodge No.

93.[x]

Also among the membership of these Lodges were other important Brethren,

Christian Missionaries. The Methodist Thomas Bertholf held membership at

Cherokee Lodge.[xi]

At Muscogee Lodge was the Baptist H.F. Buckner.[xii]

These men became acquainted with another Baptist missionary, and soon to be

Brother, named Joseph S. Murrow.

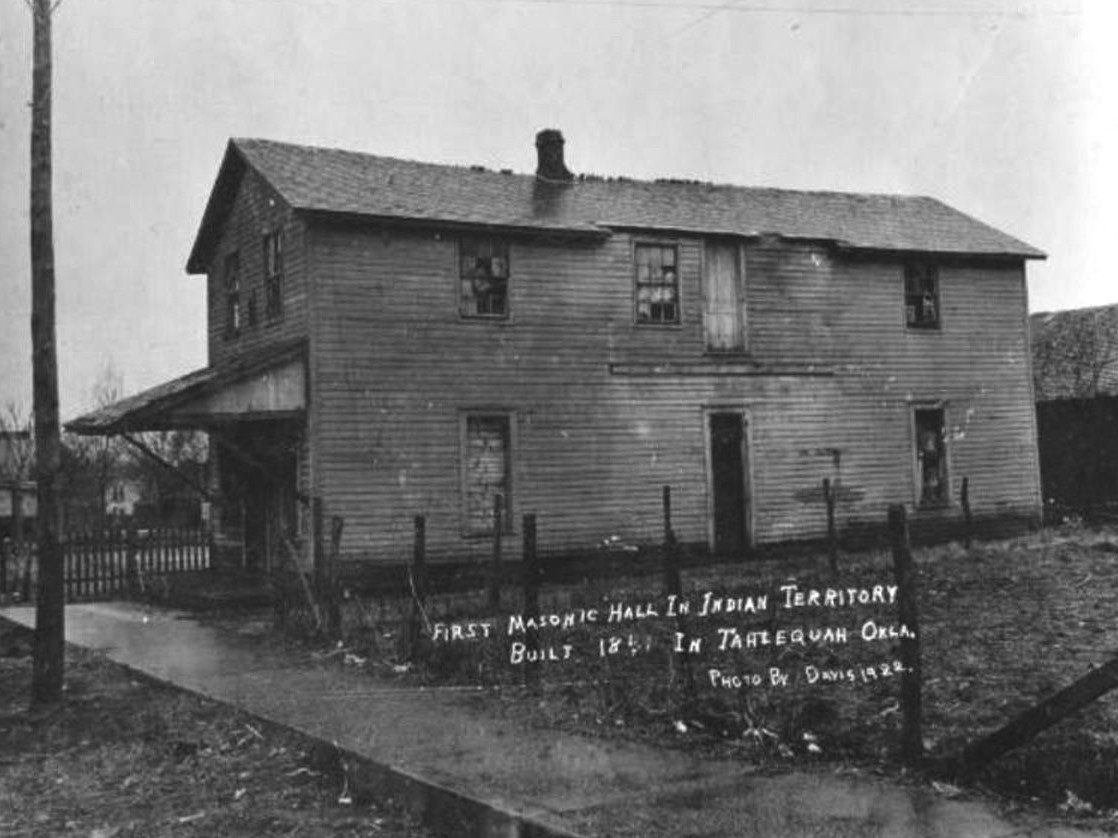

The first meeting hall of Cherokee Lodge No. 21

(Courtesy of the McAlester Scottish Rite)

Some have contended that the men of the Five Tribes found

something similar in Freemasonry that they had experienced elsewhere. There

is reference to a Choctaw “Horse Masonry” with signs and grips. Edmond H.

Doyle, an early Masonic luminary in the Indian Territory, often told a story

of meeting a non-English speaking Choctaw in 1876 in the dark of night.

Doyle, seeking shelter from a storm, gave a sign which the Choctaw

recognized and greeted Doyle with hospitality.

[xiii] Others have referenced a fraternity of “Indian Blood

Brothers” with a stone altar bearing the Square and Compasses as a familiar

sight to Native Americans, bringing them to Freemasonry.

[xiv] However, what many men of the Five Tribes saw in

Freemasonry was a connection that could help preserve their Tribal

existence. Conversions to Christianity were common among the Five Tribes in

the 19th century. Chilly McIntosh, of the Creek Nation, was

ordained as a Baptist minister by the Rev. H.F. Buckner, a Freemason, in

1848. [xv]

Chilly’s half-brother Daniel N. McIntosh, a member of Muscogee Lodge, also

became a Baptist minister.

[xvi] The men who were either responsible for providing for

the needs of the Five Tribes, or who could provide legislative influence,

were often Freemasons. For the Five Tribes, it was the Masonic Lodge that

could be turned to for schools, churches, relief agencies, and post offices.

[xvii]

The Civil War would interrupt Freemasonry in the Indian

Territory and it was particularly devastating to the region. The War did

bring two notable men to the Indian Territory. In March of 1861, Albert Pike

was appointed commissioner to the Indian Territory by the Confederacy for

the purpose of negotiating an alliance with the Five Tribes.

[xviii]

Pike had become a Freemason in Western Lodge No. 2 of

Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1850. He was elected Sovereign Grand Commander of

the Scottish Rite in 1859.

[xix] Pike, having represented

the Creek, Chickasaw, and Choctaw Nations in legal claims against the

federal government, would personally make the Choctaw Peter Pitchlynn a 33rd

Degree Mason in 1860.

[xx] By 1862, Pike had been

commissioned a Brigadier General, making him the ranking Confederate officer

in the Indian Territory.

[xxi] His tenure as a combat

general would be brief, resigning later in the year. Pike’s resignation was

prompted by orders to move his Indian Brigade outside of the Indian

Territory, which violated treaty stipulations, and due to the lack of

material being provided his command.

[xxii] Again, the men of the Five Tribes saw a Freemason who

placed their well-being first and several of the signatories of the

Confederate treaties that Pike negotiated held Masonic membership.

Also working to see to the needs of the Five Tribes at this

time was Joseph S. Murrow. Murrow arrived in the Creek Nation in 1857

to assist the Rev. H.F. Buckner, a member of Muscogee Lodge. As the federal

government withdrew from the Indian Territory in 1861, Murrow was appointed

as Confederate agent to the Seminoles; he had organized a church in the

Seminole Nation in 1859. As the situation grew worse in the Indian Territory

during the Civil War, Murrow and his family took refuge in Texas.

[xxiii]

It was in Texas that he became a Freemason in Andrew

Jackson Lodge No. 88 in 1866.

[xxiv] Murrow returned

to the Indian Territory in 1868, establishing another church at Boggy Depot.

[xxv]

It was at Boggy Depot that Freemasonry sprang to life again in the Indian

Territory with the establishment of Oklahoma Lodge No. 217 that same year.

Murrow would go on to be a charter member of the first of numerous Masonic

orders in the Indian Territory, including Indian Chapter No. 1 of Royal Arch

Masons at McAlester, Oklahoma Council No. 1 of Royal and Select Masters at

Atoka, and Muskogee Commandery No. 1 of Knights Templar. Murrow’s continued

dedication to the welfare of the Five Tribes culminated in his co-founding

of Indian University, now Bacone College, in 1880 and his establishment of

the Murrow Indian Orphans Home.

[xxvi] The men of the

Five Tribes could find no better example to emulate than that of Freemason

Joseph S. Murrow.

Joseph S.

Murrow

(An oil portrait from

the collections of the McAlester Scottish Rite)

________________________

[i]

John D. May, "Wright, Allen (1826–1885),"

The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and

Culture,

accessed August 8, 2018, http://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=WR004.

[ii]

J. Fred Latham, The Story of Oklahoma Masonry (Guthrie, OK: Grand

Lodge of Oklahoma, 1978), 14.

[iii]

Brad Agnew, “Fort Gibson,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and

Culture, accessed August 8, 2018, http://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=FO033.

[iv]

William R. Denslow, 10,000 Famous Freemasons (Trenton, MO:

Missouri Lodge of Research, 1957).

[v]

Christopher D. Haveman, “With Great Difficulty and Labour: The

Emigration of the McIntosh Party of Creek Indians, 1827-1828,” The

Chronicles of Oklahoma 85, no. 4 (2007-2008): 474-479.

[vi]

“Removal of Tribes to Oklahoma,” The Oklahoma Historical Society,

accessed August 8, 2018, http://www.okhistory.org/research/airemoval.

[vii]

“History of Federal,” Federal Lodge No. 1: Free and Accepted Masons

of Washington, D.C., accessed August 8, 2018, http://www.federallodge.org/about-us/lodge-history/.

[viii]

Charles E. Creager, History of Freemasonry in Oklahoma (Muskogee:

Muskogee Print Shop, 1935), 61.

[ix]

Rennard Strickland, “Cherokee,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History

and Culture, accessed August 8, 2018, http://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=CH014.

[x]

Creager, History of Freemasonry in Oklahoma, 20-28.

[xiii]

Charles E. Creager, A History of the Cryptic Rite of Freemasonry in

Oklahoma (Muskogee: Hoffman-Speed Printing Co., 1925), 18-19.

[xiv]

Bliss Kelly, “Are Indian ‘Blood Brothers’ Masonic?,” in Oklahoma

Lodge of Research Volume 1 (Guthrie: Oklahoma Lodge of Research,

2017), 63.

[xv]

J.M. Gaskin, Trail Blazers of Sooner Baptists (Shawnee: Oklahoma

Baptist University Press, 1953), 117-169.

[xvi]

Proceedings of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge AF&AM of the Indian

Territory (Caddo: Oklahoma Star, 1875), 24.

[xvii]

Joy Porter, Native American Freemasonry: Associationalism and

Performance in America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press,

2011), 212.

[xviii]

LeRoy H. Fischer and Jerry Gill, Confederate Indian Forces Outside of

Indian Territory (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Historical Society, 1969),

1.

[xix]

James T. Tresner II, Albert Pike: The Man Beyond the Monument

(New York: M. Evans and Company, 1995), 236-237.

[xxi]

Roy A. Clifford, “The Indian Regiments in the Battle of Pea Ridge,”

The Chronicles of Oklahoma 25, no. 4 (1947): 315.

[xxii]

Ingrid P. Westmoreland, “Pike, Albert (1809-1891),” The Encyclopedia

of Oklahoma History and Culture, accessed August 8, 2018, http://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=PI006.

[xxiii]

Andrea M. Martin, “Murrow, Joseph Samuel (1835–1929),” The

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, accessed August 8,

2018, http://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=MU016.

[xxiv]

“Joseph Samuel Murrow,” in Grand Masters of Oklahoma (Guthrie:

Oklahoma Lodge of Research, 1975), 9.

[xxvi]

“Joseph Samuel Murrow,” 9.

|