MORALS and DOGMA

by: Albert Pike

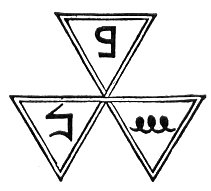

VI.

INTIMATE SECRETARY

[Confidential Secretary]

You are especially taught in this Degree to be zealous and faithful; to be disinterested and benevolent; and to act the peace-maker, in case of dissensions, disputes, and quarrels among the brethren.

Duty is the moral magnetism which controls and guides the true Mason's course over the tumultuous seas of life. Whether the stars of honor, reputation, and reward do or do not shine, in the light of day or in the darkness of the night of trouble and adversity, in calm or storm, that unerring magnet still shows him the true course to steer, and indicates with certainty where-away lies the port which not to reach involves shipwreck and dishonor. He follows its silent bidding, as the mariner, when land is for many days not in sight, and the ocean without path or landmark spreads out all around him, follows the bidding of the needle, never doubting that it points truly to the north. To perform that duty, whether the performance be rewarded or unrewarded, is his sole care. And it doth not matter, though of this performance there may be no witnesses, and though what he does will be forever unknown to all mankind.

A little consideration will teach us that Fame has other limits than mountains and oceans; and that he who places happiness in the frequent repetition of his name, may spend his life in propagating it, without any danger of weeping for new worlds, or necessity of passing the Atlantic sea.

If, therefore, he who imagines the world to be filled with his actions

and praises, shall subduct from the number of his encomiasts all those who are placed below the flight of fame, and who hear in the valley of life no voice but that of necessity; all those who imagine themselves too important to regard him, and consider the mention of his name as a usurpation of their time; all who are too much or too little pleased with themselves to attend to anything external; all who are attracted by pleasure, or chained down by pain to unvaried ideas; all who are withheld from attending his triumph by different pursuits; and all who slumber in universal negligence; he will find his renown straitened by nearer bounds than the rocks of Caucasus; and perceive that no man can be venerable or formidable, but to a small part of his fellow-creatures. And therefore, that we may not languish in our endeavors after excellence, it is necessary that, as Africanus counsels his descendants, we raise our eyes to higher prospects, and contemplate our future and eternal state, without giving up our hearts to the praise of crowds, or fixing our hopes on such rewards as human power can bestow.

We are not born for ourselves alone; and our country claims her share, and our friends their share of us. As all that the earth produces is created for the use of man, so men are created for the sake of men, that they may mutually do good to one another. In this we ought to take nature for our guide, and throw into the public stock the offices of general utility, by a reciprocation of duties; sometimes by receiving, sometimes by giving, and sometimes to cement human society by arts, by industry, and by our resources.

Suffer others to be praised in thy presence, and entertain their good and glory with delight; but at no hand disparage them, or lessen the report, or make an objection; and think not the advancement of thy brother is a lessening of thy worth. Upbraid no man's weakness to him to discomfit him, neither report it to disparage him, neither delight to remember it to lessen him, or to set thyself above him; nor ever praise thyself or dispraise any man else, unless some sufficient worthy end do hallow it.

Remember that we usually disparage others upon slight grounds and little instances; and if a man be highly commended, we think him sufficiently lessened, if we can but charge one sin of folly or inferiority in his account. We should either be more severe to ourselves, or less so to others, and consider that whatsoever good any one can think or say of us, we can tell him of many unworthy and

foolish and perhaps worse actions of ours, any one of which, done by another, would be enough, with us, to destroy his reputation.

If we think the people wise and sagacious, and just and appreciative, when they praise and make idols of us, let us not call them unlearned and ignorant, and ill and stupid judges, when our neighbor is cried up by public fame and popular noises.

Every man hath in his own life sins enough, in his own mind trouble enough, in his own fortunes evil enough, and in performance of his offices failings more than enough, to entertain his own inquiry; so that curiosity after the affairs of others cannot be without envy and an ill mind. The generous man will be solicitous and inquisitive into the beauty and order of a well-governed family, and after the virtues of an excellent person; but anything for which men keep locks and bars, or that blushes to see the light, or that is either shameful in manner or private in nature, this thing will not be his care and business.

It should be objection sufficient to exclude any man from the society of Masons, that he is not disinterested and generous, both in his acts, and in his opinions of men, and his constructions of their conduct. He who is selfish and grasping, or censorious and ungenerous, will not long remain within the strict limits of honesty and truth, but will shortly commit injustice. He who loves himself too much must needs love others too little; and he who habitually gives harsh judgment will not long delay to give unjust judgment.

The generous man is not careful to return no more than he receives; but prefers that the balances upon the ledgers of benefits shall be in his favor. He who hath received pay in full for all the benefits and favors that he has conferred, is like a spendthrift who has consumed his whole estate, and laments over an empty exchequer. He who requites my favors with ingratitude adds to, instead of diminishing, my wealth; and he who cannot return a favor is equally poor, whether his inability arises from poverty of spirit, sordidness of soul, or pecuniary indigence.

If he is wealthy who hath large sums invested, and the mass of whose fortune consists in obligations that bind other men to pay him money, he is still more so to whom many owe large returns of kindnesses and favors. Beyond a moderate sum each year, the wealthy man merely invests his means: and that which he never

uses is still like favors unreturned and kindnesses unreciprocated, an actual and real portion of his fortune.

Generosity and a liberal spirit make men to be humane and genial, open-hearted, frank, and sincere, earnest to do good, easy and contented, and well-wishers of mankind. They protect the feeble against the strong, and the defenceless against rapacity and craft. They succor and comfort the poor, and are the guardians, under God, of his innocent and helpless wards. They value friends more than riches or fame, and gratitude more than money or power. They are noble by God's patent, and their escutcheons and quarterings are to be found in heaven's great book of heraldry. Nor can any man any more be a Mason than he can be a gentle-man, unless he is generous, liberal, and disinterested. To be liberal, but only of that which is our own; to be generous, but only when we have first been just; to give, when to give deprives us of a luxury or a comfort, this is Masonry indeed.

He who is worldly, covetous, or sensual must change before he can be a good Mason. If we are governed by inclination and not by duty; if we are unkind, severe, censorious, or injurious, in the relations or intercourse of life; if we are unfaithful parents or undutiful children; if we are harsh masters or faithless servants; if we are treacherous friends or bad neighbors or bitter competitors or corrupt unprincipled politicians or overreaching dealers in business, we are wandering at a great distance from the true Masonic light.

Masons must be kind and affectionate one to another. Frequenting the same temples, kneeling at the same altars, they should feel that respect and that kindness for each other, which their common relation and common approach to one God should inspire. There needs to be much more of the spirit of the ancient fellow-ship among us; more tenderness for each other's faults, more forgiveness, more solicitude for each other's improvement and good fortune; somewhat of brotherly feeling, that it be not shame to use the word "brother."

Nothing should be allowed to interfere with that kindness and affection: neither the spirit of business, absorbing, eager, and overreaching, ungenerous and hard in its dealings, keen and bitter in its competitions, low and sordid in its purposes; nor that of ambition, selfish, mercenary, restless, circumventing, living only in the opinion of others, envious of the good fortune of others,

miserably vain of its own success, unjust, unscrupulous, and slanderous.

He that does me a favor, hath bound me to make him a return of thankfulness. The obligation comes not by covenant, nor by his own express intention; but by the nature of the thing; and is a duty springing up within the spirit of the obliged person, to whom it is more natural to love his friend, and to do good for good, than to return evil for evil; because a man may forgive an injury, but he must never forget. a good turn. He that refuses to do good to them whom he is bound to love, or to love that which did him good, is unnatural and monstrous in his affections, and thinks all the world born to minister to him; with a greediness worse than that of the sea, which, although it receives all rivers into itself, yet it furnishes the clouds and springs with a return of all they need . Our duty to those who are our benefactors is, to esteem and love their persons, to make them proportionable returns of service, or duty, or profit, according as we can, or as they need, or as opportunity presents itself; and according to the greatness of their kindnesses.

The generous man cannot but regret to see dissensions and disputes among his brethren. Only the base and ungenerous delight in discord. It is the poorest occupation of humanity to labor to make men think worse of each other, as the press, and too commonly the pulpit, changing places with the hustings and the tribune, do. The duty of the Mason is to endeavor to make man think better of his neighbor; to quiet, instead of aggravating difficulties; to bring together those who are severed or estranged; to keep friends from becoming foes, and to persuade foes to become friends. To do this, he must needs control his own passions, and be not rash and hasty, nor swift to take offence, nor easy to be angered.

For anger is a professed enemy to counsel. It is a direct storm, in which no man can be heard to speak or call from without; for if you counsel gently, you are disregarded; if you urge it and be vehement, you provoke it more. It is neither manly nor ingenuous. It makes marriage to be a necessary and unavoidable trouble; friendships and societies and familiarities, to be intolerable. It multiplies the evils of drunkenness, and makes the levities of wine to run into madness. It makes innocent jesting to be the beginning of tragedies. It terns friendship into hatred; it makes a

man lose himself, and his reason and his argument, in disputation. It turns the desires of knowledge into an itch of wrangling. It adds insolency to power. It turns justice into cruelty, and judgment into oppression. It changes discipline into tediousness and hatred of liberal institution. It makes a prosperous man to be envied, and the unfortunate to be unpitied.

See, therefore, that first controlling your own temper, and governing your own passions, you fit yourself to keep peace and harmony among other men, and especially the brethren. Above all remember that Masonry is the realm of peace, and that "among Masons there must be no dissension, but only that noble emulation, which can best work and best agree." Wherever there is strife and hatred among the brethren, there is no Masonry; for Masonry is Peace, and Brotherly Love, and Concord.

Masonry is the great Peace Society of the world. Wherever it exists, it struggles to prevent international difficulties and disputes; and to bind Republics, Kingdoms, and Empires together in one great band of peace and amity. It would not so often struggle in vain, if Masons knew their power and valued their oaths.

Who can sum up the horrors and woes accumulated in a single war? Masonry is not dazzled with all its pomp and circumstance, all its glitter and glory. War conies with its bloody hand into our very dwellings. It takes from ten thousand homes those who lived there in peace and comfort, held by the tender ties of family and kindred. It drags them away, to die untended, of fever or exposure, in infectious climes; or to be hacked, torn, and mangled in the fierce fight; to fall on the gory field, to rise no more, or to be borne away, in awful agony, to noisome and horrid hospitals. The groans of the battle-field are echoed in sighs of bereavement from thousands of desolated hearths. There is a skeleton in every house, a vacant chair at every table. Returning, the soldier brings worse sorrow to his home, by the infection which he has caught, of camp-vices. The country is demoralized. The national mind is brought down, from the noble interchange of kind offices with another people, to wrath and revenge, and base pride, and the habit of measuring brute strength against brute strength, in battle. Treasures are expended, that would suffice to build ten thousand churches, hospitals, and universities, or rib and tie together a continent with rails of iron. If that treasure were sunk in the sea, it

would be calamity enough; but it is put to worse use; for it is expended in cutting into the veins and arteries of human life, until the earth is deluged with a sea of blood.

Such are the lessons of this Degree. You have vowed to make them the rule, the law, and the guide of your life and conduct. If you do so, you will be entitled, because fitted, to advance in Masonry. If you do not, you have already gone too far.

![]()